By Annie McNamee, Co-Editor-in-Chief

I’m in a small, windowless room in a hospital somewhere in the south of Glasgow. To my right sits my dad; he’s fiddling with a bottle of Coke, I’m fiddling with a bag of tangerines. I’m meant to be in a seminar 400 miles away discussing politics in Fahrenheit 451 or Lolita, but instead I’m sitting here, staring at an empty wall, waiting to see my mum.

The last time I had seen her was about three weeks prior, the day before I flew back to Bristol from home in Glasgow. By that point her health – mental and physical – had been declining for months. I had tried everything I could think of to cheer her up; daily walks to Costa, family movie nights, I even bought her a journal. When mental illness really gets a grip on a person, however, there isn’t much you can do – at least not without professional help. On February 3 2024, my mum was sectioned and began a three-month stay in a psychiatric ward.

Her story is hers to share (which she has!), but illness never just impacts one person. It worms its way into every part of life like a carnivorous jelly, consuming family members and friends along the way. So, I have my own story to share. My experience is no more or less important than anyone else's, but it’s the only one to which I have complete access – and the one I could have done with reading this time last year.

This wasn’t my introduction to mental illness. I’ve gone through the Student Health Services four or five times for various ailments, and more of my friends have taken Sertraline than Ketamine, which is saying a lot in Bristol. I thought I knew what bad mental health looked like, but I’d never watched it take someone over so completely. The experience was alien, so I didn’t have the language to describe what was going on even if I’d wanted to. Luckily, though, I didn’t feel the urge.

Knowing that people might treat me differently or give me concessions I didn’t need made me want to crawl out of my skin. I am sentimental when it comes to childhood teddy bears and birthday cards, but I’m also from Glasgow, so I’m cursed with the inability to be too sincere about anything. Where I would have usually communicated with humour, I was left mute. There wasn’t much funny about the situation, and jokes only made people (understandably) uncomfortable. I got to know the exact grimace Nathan, my extremely English boyfriend, makes when he’s thinking, ‘I’m not sure if this is a joke or if you meant that’ very well.

This is when I began to realise how much of a taboo exists around the very concept of a psychiatric hospital. I found it easy to explain to people that my mum was unwell, but got a lump in my throat when I had to explain how. When I did, people got tense. Over 52,000 people were sectioned under the Mental Health Act in the UK in 2023-24 – and the number is rising – which means that statistically, someone in your life probably knows someone who has been hospitalised due to their mental health. So why are we still unable to talk about it?

‘Those living in less affluent areas are three and a half times more likely to be admitted to an inpatient mental health facility’

We have hidden the realities of mental illness from public view. You can picture someone going into surgery, doctors rushing down halls wheeling half-conscious patients as they shout for fluids; such a clear image of psychosis doesn’t exist in the cultural mind. The concept of a psychiatric ward sounds Victorian. You think of One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest or The Bell Jar, of dungeons or electric shocks or straightjackets. Clearly, this is not a gracious picture.

But it’s not the 1960s anymore, and being an inpatient saved mum’s life. It was tough – on her, on my dad, my seventeen-year-old brother, even my dog sensed something was up – but it was essential. The nurses at Leverndale hospital who looked after her are real-life superheroes; they are paid very little for long shifts taking care of patients who are often aggressive or unresponsive. At the depth of mum’s illness, her nurses were kind to her, and able to care for her around the clock in a way that wasn’t possible at home. It’s essential that we get better at discussing the realities of psychiatric care not only to better recognise early warning signs in our loved ones, but to give credit to the doctors and nurses who dedicate their lives to caring. These facilities and their staff members respect the dignity of their patients, and they don’t deserve to exist under the shadow of the ‘insane asylums’ of the past.

Living where I live, and having as strong a relationship as my family does, we were the lucky ones. Not everyone has someone at home who can help them readjust after being discharged, nor is there a hospital bed free for everyone who needs it. Those living in less affluent areas are three and a half times more likely to be admitted to an inpatient mental health facility, and if you don’t have a safe place to go back to, you’re much more likely to end up back in hospital. By not talking about the realities of mental illness, and how they can affect anyone, we do our most vulnerable neighbours a great disservice.

I’m not embarrassed by what happened to mum. In fact, I’m very proud of her. It’s one thing to detail how hard she worked in recovery, how excellent the standard of care was at Levernale. It’s another to explain how it all made me feel.

When it comes to my own experience, I have a severe case of proverbial lockjaw. Nobody, perhaps even including me, knew exactly how I was keeping last year. I threw myself into my uni work, and in a bizarre twist of fate, my grades started to improve. I took on more shifts writing for Time Out. I signed up for various societies and applied to be Editor-in-Chief of this paper. I went to the Eras Tour three times, got a radio show on Burst, returned to musical theatre for the first time in years, set up a campaign against mould, won a few awards, and refused to miss a single seminar. For an outsider, I just looked like I was having a great year. In reality, I was doing anything I could to avoid thinking for too long. As far as coping mechanisms go, I suppose it’s better than becoming a smoker or getting into skydiving.

But it didn’t feel right to finish university, where I spent most of my time writing for Epigram, without writing about the thing that shaped much of my university life, particularly because this paper has been such a rock for me throughout.

Which brings me back to that room in that Glasgow hospital last year. My mum wasn’t very talkative at the depths of her illness, but every time we sat in that meeting room together, there were two things she’d ask me: How’s Nathan? How’s Epigram? Maybe there was something magical about these two specific parts of my life that permeated the barrier between my mum and I at the darkest times, that allowed for some connection to each other when we both needed it most. Or maybe I just never shut up about my newspaper or my boyfriend and so branded them into her brain forevermore. I’ll leave you to decide which you prefer.

‘I had no idea how many people around me would be willing to help carry all this extra emotional baggage’

When I began writing this article, I wanted to write what I needed to read last winter. I remember feeling so guilty for not being at home to help out, or for feeling anything bad at all when mum was struggling so much. I needed to be strong, to get up and do my work and not let my family down when they needed me most. I put such a huge pressure on myself to deal with the experience ‘properly’, but there’s no such thing. I felt I had to deal with this monster alone, because I had no idea how many people around me would be willing to help carry all this extra emotional baggage I found myself with.

Watching my mum become unwell was also watching my dad care for her day and night. Visiting her in hospital was watching dozens of staff members who had dedicated their lives to helping people in her position do thankless work because it mattered, because they cared. Struggling myself was seeing how the people around me rallied to help me keep going. My friends bought me treats and sent me cards to let me know they were thinking of me, and, of course, Nathan was there day and night. Giving me a hug when I couldn’t sleep, cooking me dinner when I forgot to eat, walking me to uni when I didn’t want to go alone. It is only in the very darkest of times that you realise how many people there are in the world willing to hold up a light for you.

‘All of that lives within me, haunts me sometimes, but I’m glad it does’

If you hit rock bottom with enough velocity, the rules of physics dictate that you’ve got to bounce back up, and so mum did. She was discharged at the very end of April, just before my twenty-first birthday. By the time I held my party a month later, she was up dancing. She’s been at home – except when we went on holiday to Naples – and feeling better ever since. That would not be the case had she not spent three months in hospital.

A year later, it’s not over. The feelings linger, the worry that somehow things might take a turn for the worse is always buzzing at the back of my mind, and sometimes I close my eyes and find myself back in that Leverndale waiting room. Few memories are etched into my mind as clearly as that one. Sometimes I can even still smell the hospital, that care-home mix of medicine, bleach, vomit, and sweat. All of that lives within me, haunts me sometimes, but I’m glad it does. I don’t want to forget because I don’t want to stop remembering that we got through it.

Mental health awareness week: In conversation with Bristol Nightline

Put the phone down and protect your brain - you'll thank me later

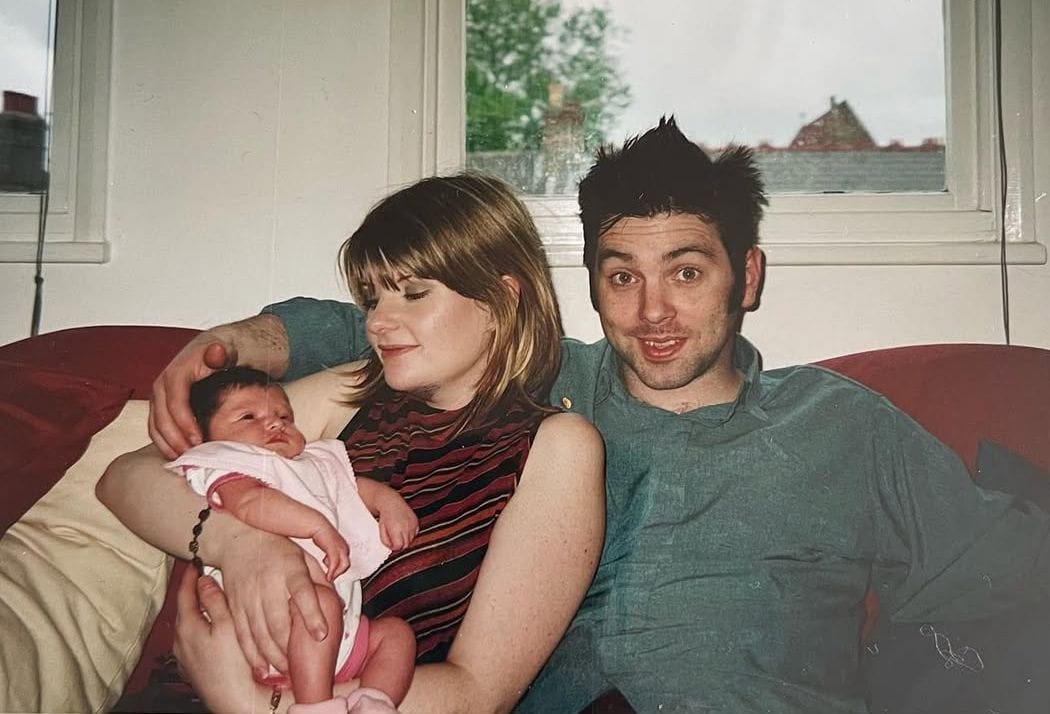

I am, probably more than most, my mother’s daughter: she studied Film and English at uni, as do I. She taught me to cry at every movie, how to do eyeshadow (she still does it better than me), brought me up to be politically active and interested, and neither of us would be caught dead at a campsite. She’s even a journalist. I can’t overstate how much of me I owe to her, and I hope that in the past year I’ve been able to give a little of that care and love back.

Featured Image: Epigram / Annie McNamee