By Katie Ramamoorthy, First Year, English

It’s easy to assume that music today should be more diverse than ever. In an age of the ‘shrinking-world phenomenon’, in which people on opposite sides of the planet are just one click away, global sounds have the opportunity to merge, create combinational genres, and popularise new sounds. Music has the potential to be more sonically adventurous than ever before; a global collaborative effort.

Paradoxically, the opposite in some cases may seem true. Walk into any chain store, scroll through TikTok, or turn on the radio; and you might begin to notice something strange: every song has begun to sound the same.

Reaching new heights of sonic diversity

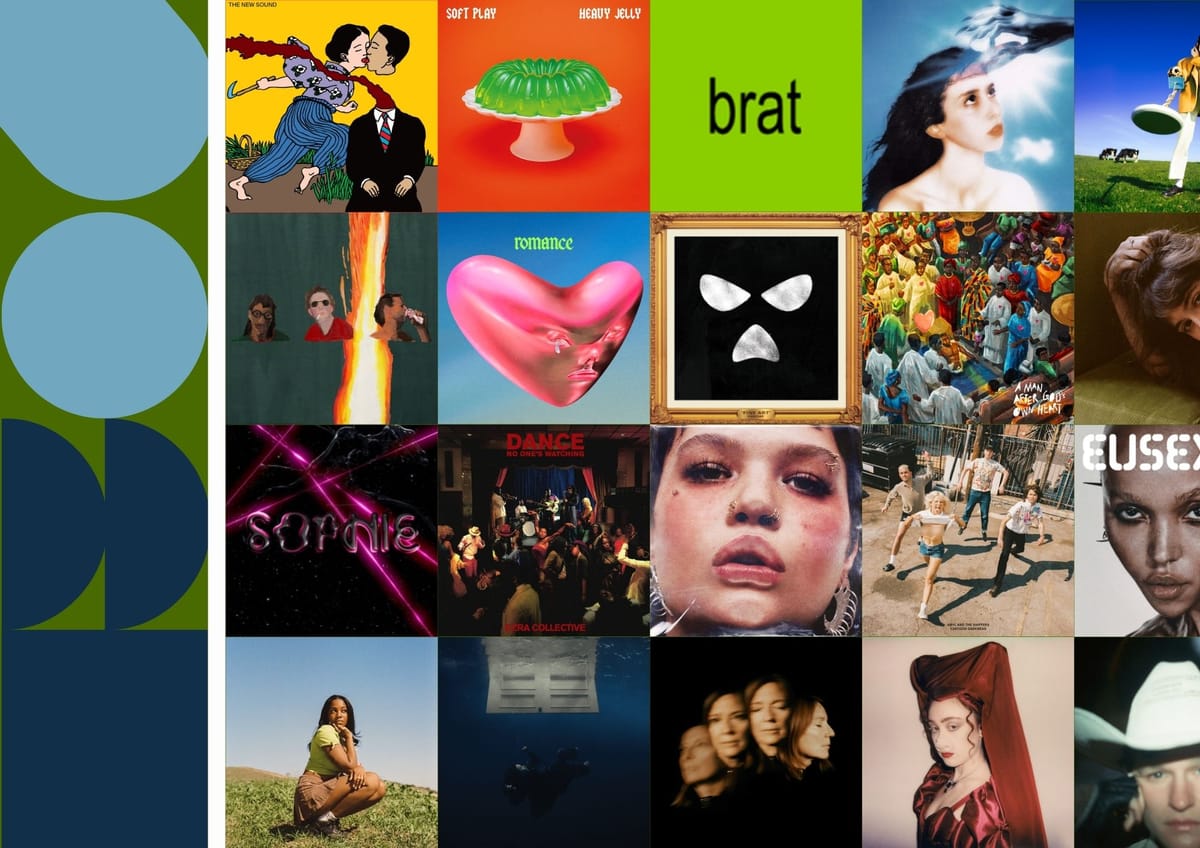

To say music isn’t sonically diverse now would be a lie. Charli XCX’s brat, Clairo’s Charm, and Chappell Roan’s The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess are all three recently released albums which have all prompted new levels of critical acclaim for each respective artist, and yet all sound drastically different.

brat is a hyper-pop club album with a steady pulse running through it, built from metallic synths, punchy percussion, and introspective lyrics. Charm is an antithesis to this highly technologised pop: with soft vocals, vintage instrumentals, and the warmth of live recordings for each track, the album has a steady heartbeat — Cottrill herself commenting that she ‘likes to sing as if she is sitting on the listener’s lap’.

‘I want to [record vocals] like that. I want [listeners] to feel like I’m in their lap, telling them things in their ear.’

Meanwhile, Chappell Roan centres around 80s synth-pop: colourful and theatrically big songs, complete with backing choruses and on-stage drag outfits. These three popular artists have three extremely different sonic worlds - proof that adventurous, boundary-pushing music is still being made, and often celebrated.

Anyone with a laptop can get their foot in the door

Technological innovations that make it easier than ever before for DIY artists to create and upload their music. Troye Sivan, who’s 2023 hit single ‘Rush’ has over 500 million streams, started his career by making music and videos on YouTube, before signing with a record label in 2014. Claire Cotrill, aka Clairo, rose to popularity after her bedroom-pop song ‘Pretty Girl’ garnered over 16 million views on YouTube. PinkPantheress was offered her first major-label deal in 2021, after going viral on TikTok with her self-produced, short-form songs that combined classic UK garage & pop music.

The music industry is arguably no longer an intangible space reserved for a select few people with enough money or connections; it is available to anyone with wifi and a laptop*. Rachel Newman, co-head of Apple Music, wrote recently that ‘Anyone, even a new artist making music out of their bedroom, can have the next big hit’.

*This is not taking into account issues such as nepotism within the music industry — so take this with a grain of salt — but that’s an article for another day.

But the charts often homogenise. When it comes to what dominates the airwaves, the picture narrows. A small handful of artists hold monopolies year after year — on label support, playlist placements, and marketing budgets. This concentration of power creates a loop in which the same few names and sounds are cycled through endlessly.

Can artists afford to take their time on music anymore?

Increasingly, the speed of music consumption is accelerating. In an age where AI can craft a full length song in a matter of seconds, and 120,000 tracks are uploaded to global streaming services each day, there is a pressure to value quantity over quality in the face of increased competition: throw something at the wall, often the same thing again and again, until something sticks. Artists now have a pressure to capture listener’s attention within the span of just a few seconds, churning out a hamster wheel of viral TikTok soundbites in the hope of exposure.

In the wake of constantly-released new music, online attention and acclimation is extremely volatile - ‘The complexity of being able to separate one’s music from the other 99,999 tracks uploaded that day is complex [and] incredibly difficult’, explained Warner Music Group CEO Steve Cooper.

In order to retain people’s attention, there is now more financial incentive to monetise 37 versions of one project than to take time out of the industry to build something new from scratch. And while criticisms about monetary greed are often disproportionately aimed at women in pop as a result of underlying misogyny, the broader truth is that media in general is under pressure to be produced faster and more frantically than ever before.

Spotify’s former Chief Economist Will Page put it plainly in an interview with Music Radar: ‘More music is being released [in a single day] than was released in the calendar year of 1989’.

New Music Friday, Every day

Music has never been more sonically diverse, and yet the most visible spaces - radio, TikTok, Top 40 charts - often feel more homogenised than ever. Beneath the immediacy of TikTok sounds, today’s musical landscape is brimming with difference. Four of 2024’s most popular albums couldn’t sound less alike. Even at the top of Spotify’s most streamed lists, there’s a surprising amount of range, from club anthems to indie folk to bedroom-pop.

The question isn’t whether diverse music exists — it does, and (hopefully) always will. The question is whether the structures that affect what we hear; such as streaming algorithms, shorter attention spans, and label marketing — allow that diversity to shine through.

Featured image: Epigram / Sophie ScannellDo you think music is becoming more or less sonically diverse?