By Sasha Ramtohul-Akbur, Third Year, English

I’m aware that being at least partially a product of our environment is par for the course. However I doubt I’m alone in admitting that when I was preparing to go to university, I retained hope that I was finally getting a blank slate. Character development is inevitable at university, but I’ve noticed that I’ve been involuntarily perpetuating home dynamics. Though this feels like evidence of personal regression, I know that this harsh judgement could be partially allayed by knowing that other students also maintained past patterns. However having never actually discussed this topic whilst at university, I’ve guaranteed that my chances of finding solace through sharing common ground stand at a big, fat zero. I promise I am not just Baader-Meinhof-ing my experience for my own self-assurance, but as an attempt to instigate a little reassurance I’ve asked students at the University of Bristol if they feel that their homegrown habits have reappeared despite the changed circumstances.

Whilst I felt I had regressed at university, because no-one knew me before, this meant I was free to turn a blind eye to my lack of development. Initially I welcomed that opportunity to stop monitoring myself and to only exist outwardly, but in my case that meant I fell into old patterns, and nobody saw this as negative but me.

For instance, my instinct to go to any lengths to support my new friends to my detriment was hardly a red flag, and I initially viewed this as an admirable quality. This will sound like a play at martyrdom, so suspend judgement for a couple of sentences: I’ve historically felt that I am only what I am to other people. I am patient with my friends, which makes me understanding; I make my friends feel better, which means I am a positive influence, and I can put their interests above mine without being asked, which means I am selfless. Unfortunately, the consequences of shortcutting my way to identity is that a) on my own I felt like a boring person and b) this was yet another opportunity to stop caring for myself.

‘in more extreme cases where supporting others swamps everything it’s hard to initially identify yourself outside of the known network’

Being auxiliary to others to glean a little value was less pragmatic and more Pavlovian. This instinct was probably a result of the subversion of child and adult roles in my childhood, where I was valuable because of how I helped. This is sometimes called ‘parentification’, which The Attachment Project has defined as when ‘the caregiver relies on their child for emotional or practical support’. I don’t think parentification is necessarily detrimental to development, but in more extreme cases where supporting others swamps everything it’s hard to initially identify yourself outside of the known network. Considering university as a chance to embrace individuality (at this point, originating a society must feel like discovering a new colour), it felt alienating to admit that this was an adjustment rather than a natural progression.

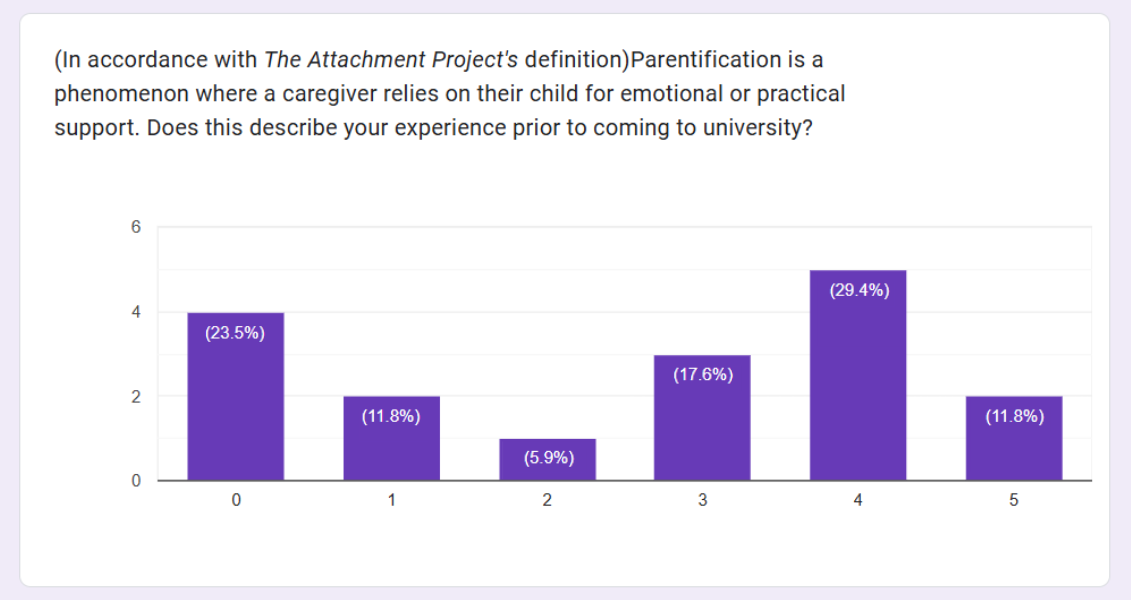

I posted a survey on my Instagram asking whether students at the University of Bristol felt that being parentified affected their ability to engage with student life. Using The Attachment Theory’s definition, on a scale from zero (they didn’t feel parentified at all) to five (supporting others felt like their main responsibility growing up), around 60 per cent placed themselves between three and five on the ‘parentification’ scale, which I’ve identified as heavily parentified. Some of those who were heavily parentified corroborated how I felt, reporting how a past of protecting others led to being the one that kicks off at pervs in the club or looks after the stumbly one on the way home. Similarly to my own experience, several mentioned how the practice of prioritising others led to a neglect of themselves.

Considering this as a common consequence where self and external care were inversely proportional helped me understand that self-neglect is due to a lack of balance, due to a general lack of practice which feels easier to change. The universality of learnt behaviours being repeated at university was illustrated by the fact that 100 per cent of those who identified as being somewhat parentified (in the one to five range) asserted that the responsibilities they had at home did affect how they operated at university. Even something as small as washing dishes immediately after use was instinctively continued at uni.

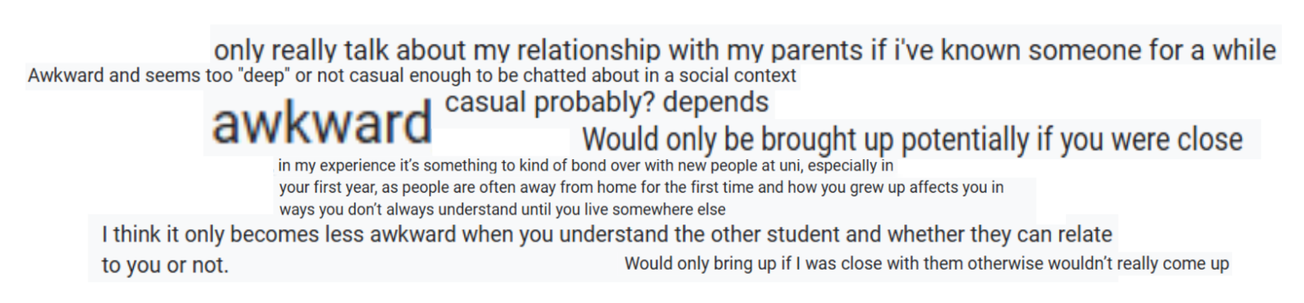

Conversely, whilst repeating parentified behaviours felt like evidence of my personal regression, others who also identified as heavily parentified saw this as evidence of growth. For example, a couple of people mentioned that the duty of care that they learnt as a child gave them the skillset to identify uneven power dynamics or be emotionally in tune with others, which provided an earnest sense of pride, revealing that parentification isn’t inherently negative and can make for fairly casual conversation. However, when I asked whether this was something they’d talk about at university, the responses were primarily, ‘no’. Such conversations could only be had with ‘close friends’, with several people feeling that the conversation would be ‘embarrassing’ and ‘not casual enough’.

We can agree that recreating behaviours from home is hardly ground-breaking, but its general omission from discussion suggests that it doesn’t feel discussible at our university. Despite my interest in understanding whether the way I feel is characteristic of the Bristol experience, admitting that I feel somewhere behind where I should be at this point in my life feels too embarrassing. Naturally, like the majority of those surveyed, I just squirrel the conversation away for when I see my best friend at the pub back home.

To understand why this feels so difficult to discuss at university, I asked what those surveyed felt were the characteristics of the typical University of Bristol student. I received ‘privileged’, ‘always out’, and ‘Carhartt’. Here, what is perceived to be valuable to University of Bristol culture tends to be an outgoing and individualistic mentality. It then makes sense that being ‘embarrassing’ or not being ‘casual enough’ was an obstacle to having the conversation, when image and showboating feel so prevalent.

To conclude, being lost in the lifestyle is one of the best parts about going to university, but this doesn’t have to be at odds with vulnerability - looking a bit closer shows everyone’s compensating: ski-season pass holders calling the newsagent 'bossman', performative male competitions (no, I’m not talking about the scheduled one) and Tories wearing Fontaines DC football shirts. All I'm saying is if you want to punctuate time here by discussing regression or growth, it's a more welcome interruption than you'd expect.

Featured image: Epigram / Sasha Ramtohul-Akbur

Do you wish that you could open up about your home experiences at university?