By Morgan Williams, Second Year History

Bristol from as early as the 13th century provides a captivating case study for the illicit trading economy of Britain’s coastline. It held an opportunistic and entrepreneurial spirit unmatched throughout the country because of merchants who used increasingly illegitimate tactics in order to deliver their cargo. Whilst this is not a story of the romanticised pirate culture, the inherent corruption and trickery will make you shake in your boots. Only a summary for the context of Bristol’s smuggling can be gleaned by focusing on wine, because methods of smuggling became as sophisticated as the tax it was trying to dodge.

Fundamentally Bristol had all the right tools at its disposal to become a great port city. ‘Bristol’ as a word literally means place by the bridge. One of the earliest know facts about the town is its bridge, still situated today in the city centre. The cities early development and funding came through this, as a bridge allowed markets to be placed in surrounding areas for travellers. Many of these are still functioning today such as St. Nicholas’ market which helps to maintain the Bristol’s compelling connection with the past.

Merchants would have also benefited geographically as the port is situated on the River Avon next to the junction between the Severn Estuary and the channel. This allowed ships to have access to trade routes including Wales, Ireland, France, Iceland and later the Iberian coast. Unlike other places in England, Bristol merchants owned the ships that they were sailing, whilst ports such as London harboured ships owned by other countries like Italy. If we see merchants at this time like a modern day entrepreneur, the success of their ships was based on navigating and exploring the ocean for trade.

One of the key imports into Bristol around the 15th century was wine from Bordeaux, taking up around half of trade. Although it was seen as a signifier of status, the drinking culture was completely different. Alcohol was generally thought to be safer than water, and so an average person would consume around 8 pints of beer or ale a day, and the upper class would drink around 2 pints of wine. Whilst it maintained a crucial role within society, relations between the British and French monarchies put its supply at risk. The end of the 100 years’ war in 1453 meant that Bordeaux was now occupied by the French who were unwilling to allow any merchants to export their wine. Bristol traders took this as an opportunity to diversify their trade, and started to develop links with the Iberian coast.

The sale of wine around this time had relatively low import taxes, meaning it wouldn’t have been worth it for merchants to smuggle the goods in. However, as shown by research from Simon, wine taxes went from 2.5% to 44% literally overnight. Although the crown could theoretically implement these changes to increase revenue, it actually pushed merchants to turn to illicit methods in order to survive. One of the key aspects of this smuggling was the inherent corruption of ports. ‘Customs officials’ had to both record and supervise trade to maintain the crowns revenue. The two main adjudicators were the ‘collectors’ and ‘controllers’ which oversaw the complicated tax system. However, the officers usually had low pay and gained their position through patronage, rather than skill or desire. Bribes rapidly became commonplace, acting almost as a pseudo tax.

Reports by the crown show that whilst they knew about this problem, nothing could really be done to stem the cause: officials working for the state with a conflict of interests. Customs officers were banned by law from being involved in international trade, yet could engage in domestic trade. Building a business relationship with a merchant-smuggler meant that officials were more likely to turn a blind eye to certain goods being transported, such as Anthony Stanback who became a vintner and bought John Smyth’s, a known smuggler, stock of wine. Not only did this allow smugglers to become increasingly bolder, they were protected by officials. Cases show officers helping to hide and regain illicit cargo, even helping them in court if they had a case against them.

These practices were common across Britain, and Bristol’s illicit trade increased as it became the second most important port in the country. Historians research into this area has been tentative though because of the limited quantifiable evidence for the amount of smuggling. The ‘customs accounts’ provide a large amount of data about the amount of trade that was occurring, through records of all the ships that entered and left the Bristol port and their cargo. However, estimates can only be made as to how reliable this realistically is, due to the level of corruption and trading with contraband.

Whilst the illusive nature of this topic has shrouded conceptions of what it was like to be a merchant-smuggler, comparisons can easily be made to modern day. Bristol has gained a reputation for being alternative, and the merchants of the time were no exception forging both new trade routes and methods to evade tax. Whilst in more recent understanding the Bristol port has gained attention due to its role within the transatlantic slave trade, study of its transition from the medieval period into its prominent position highlights its rich past beyond this. The city was shaped by the economy that was brought from this shipping, either legal or illegal, and remnants can still be seen in the built environment. The longstanding nature of the markets, roads and records from this time are a testament to the influence that Bristol’s merchant smugglers had.

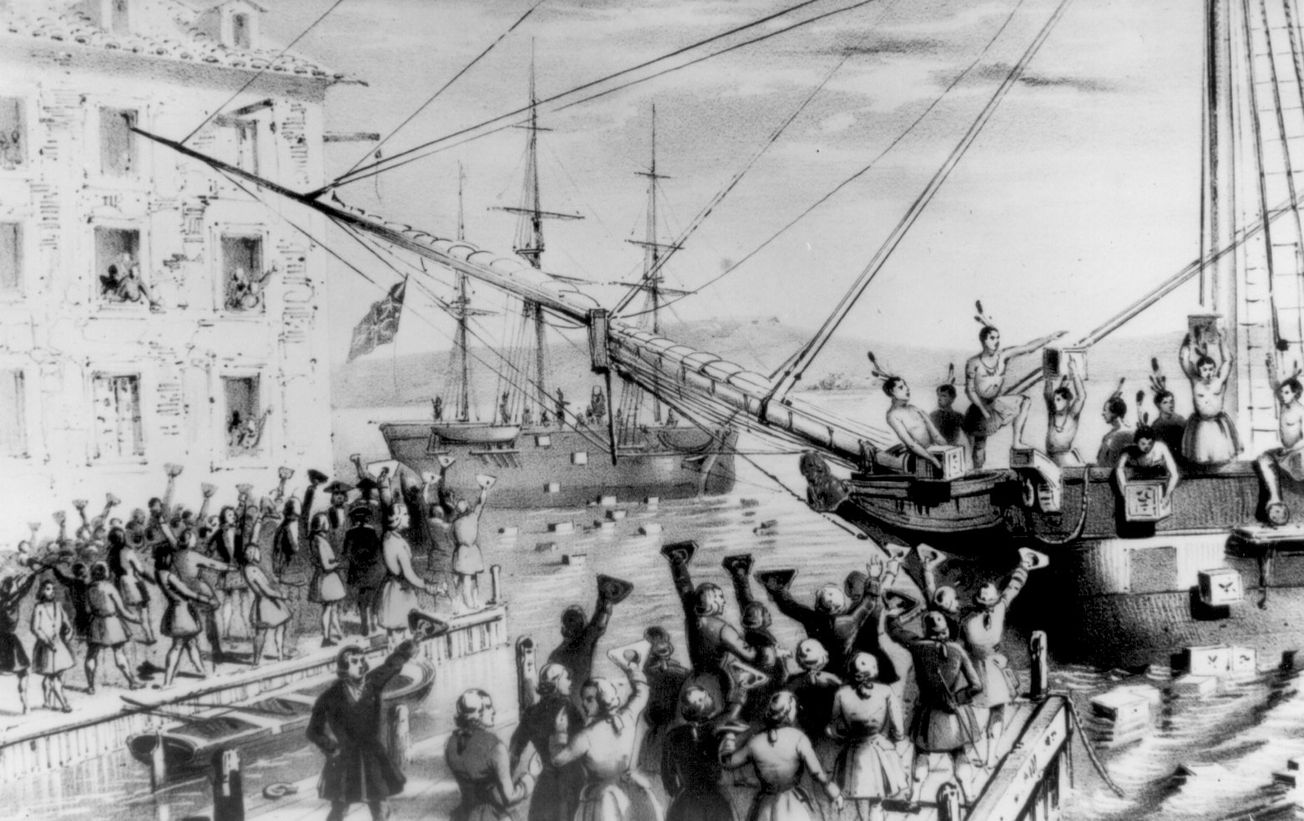

Featured Image: Wikipedia