By Nina Bryant, Deputy News Editor

Nina Bryant discusses the difficulties she dealt with when recovering from and managing a restrictive eating disorder.

When in the grips of a restrictive eating disorder, you may often be told the phrase ‘food is fuel’. You may also not believe it. I did not believe it; I simply did not think it applied to me. I was suffering terribly with moral scrupulosity OCD, and restricting my food intake was a form punishment.

I blindly thought that other people just did not understand that for me there was a bigger picture. I had heard that the co-morbidity for OCD and anorexia was high, and that sufferers with OCD were more likely to have a chronic condition. I thought it was something that I could do nothing about and, worse, I thought doing something about it would be perceived as an undeserved act of self-care. A reality I have become aware of is that there is always a bigger picture when it comes to an eating disorder, but that doesn’t make food any less important. In reality, when you are suffering mentally - as people with eating disorders are - maintaining a stable energy intake is of even more vital importance.

In reality, when you are suffering mentally - as people with eating disorders are - maintaining a stable energy intake is of even more vital importance.

Despite this, rarely is the phrase ‘food is fuel’ ever followed by ‘for your brain’. The brain is an organ just like any other, and uses up a huge amount of your daily energy intake. Whilst the rest of your body will definitely suffer - regardless of your body weight - keeping you alive during periods of restriction is your body’s first port of call.

Anything beyond basic survival - like maintaining good relationships and engaging with academic work - is sacrificed for the sake of survival and replaced with obsessive thoughts about food. This heightened sense of motivation is often mistaken for ‘excess’ energy or, sadly, a sign that you are ‘eating too much’. Mental depletion is an important topic of conversation because it is a nasty symptom of any eating disorder, but does not have anything to do with what you look like. Unfortunately, eating disorders are primarily measured as a physical illness, contributing to the illusion that you have to be ‘sick enough’ or look a certain way in order to deserve treatment.

Mental depletion is an important topic of conversation because it is a nasty symptom of any eating disorder, but does not have anything to do with what you look like.

My personal experience

When I was at my worst I could not remember how to do the most basic things. My ability to pay attention to things was horrific and pretty much any thought I had that was not related to food and weight was something negative about myself, or my relationships with other people. The biggest focus of any day was simply making sure I didn’t pass out in public; most days I literally just wanted to die.

My grades suffered drastically; something I am now managing to deal with the consequences of. Worst of all, I only felt more and more worthless as I let my eating disorder drive all of my thoughts and behaviours. I was difficult to connect with, and I am almost certain that I was difficult to talk to because my brain was stuck on a loop of about three topics of conversation.

Having a brain that unfortunately falls into patterns of irrational compulsivity far too easily, I became horribly obsessed with seeing the numbers on the scale as a marker of how sick I was, rather than the fact that most of the time I felt completely out of touch with everyone around me. I could barely get my head around doing the most basic of things; I was living in another world and it was a scary place to be.

It sounds incredibly cliché, but I look back at who I was a year ago and I do not recognise myself. I would be impossible to recognise because I was barely even a person; I would be impossible to recognise not because I looked all that different, but because I was almost incapable of having any kind of personality. It was a way of hiding from absolutely everything, but this included all the good things too.

Can things get better?

It is a tragic illness, but there is a good take home message that comes from all of this: the answer can sometimes be as simple as ‘just eat’. If you have an eating disorder you have definitely heard this phrase before and I do not blame you if it has filled you with frustration or feelings of being misunderstood.

This is why it is important to hear it from someone who has felt the frustration. Eating will only improve things; it is okay if sometimes eating feels easy. Being bombarded with thoughts of ‘this is too easy - maybe that means I’m not ill at all’ is enough of a struggle. Eating is supposed to be easy - we are biologically wired to find it rewarding. Worrying about whether eating is too easy is already more difficult than eating should be. Some days, recovery is going to be easy, and it’s important to know that that is okay.

It is also okay if sometimes eating is harder, but be aware that eating too little could bring back those thoughts again. I now notice whenever I forget or don’t make time to eat enough I fall back into the trap so quickly it can take me a couple days to get out of it. It is a horrible trap; it is a trap that feels far too horrible to have a simple solution. But in recovery I have learnt that the first step is always to eat and not to think about it, even if my body does not feel like it. Some days, recovery is going to be hard, and that is okay too.

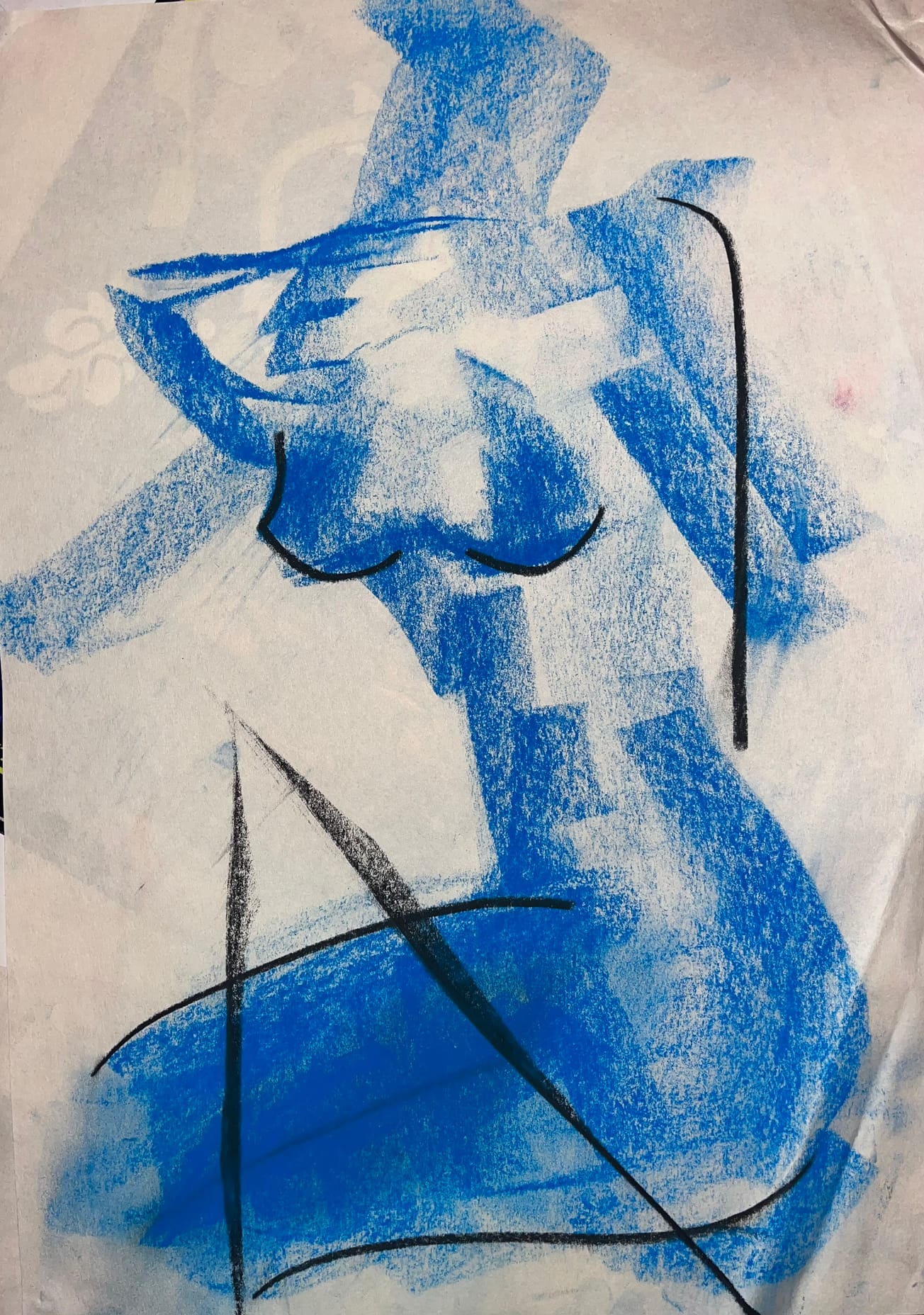

Featured Image: Epigram / Jasmine Burke

If you feel that you could benefit from help regarding any issues related to this article, contact the student health service, or ring the Beat student line at 0808 081 0811.