By Emma Coleman, Film & TV Subeditor

Do ‘classic’ novels truly stand the test of time or have they become performative?As a student of English Literature from secondary school to university, I have come across a multitude of classic novels both in and out of the classroom. Some have been life changing, some were simply a good read and some I thought ‘wow, this was really what all the fuss was about?’. Now, in 2026, I ask the question, do these books labelled as ‘classic’ still really matter today, or are we now simply reading them to feel academic?

The Guardian states the key definition of these stand-out books is that Classics have stood the test of time and convey as much to readers in 2012 as they did in 1912. I find this to be the most helpful way of understanding the concept of ‘classics’; they are simply books that can never fade as they are so imbued with worldly knowledge and universal themes that they will always be applicable. This is already very problematic because we live in a very different society to 1912, and even 2012 when this definition was written and, as a result, we must question whether they can mean the same to us now.

Then we have T. S. Eliot claiming ‘No modern language can hope to produce a classic, in the sense in which I have called Virgil a classic. Our classic, the classic of all Europe, is Virgil.’ From this we gather what we understand as classics cannot be so, and the entire concept of a classic is a distorted shadow of this original Roman poet. Finally, we have Italo Calvino giving us a short, simple list of 14 things that make a classic, that both agree and disagree with what I have already said. I don’t know about you, but my head hurts!

Whilst the concept of a ‘classic’ is a very blurred line, what I will be discussing is whether these books labelled as ‘classics’ still hold the same power today as they did in the period when they were written? Strangely, many classics books were actually not well regarded in their time and it was only when scholars rediscovered them, that they got their golden status. Simultaneously, some were immediately popular. With this variation in reception they cannot possibly mean the same in their time period as they do in their contemporary glorified position.

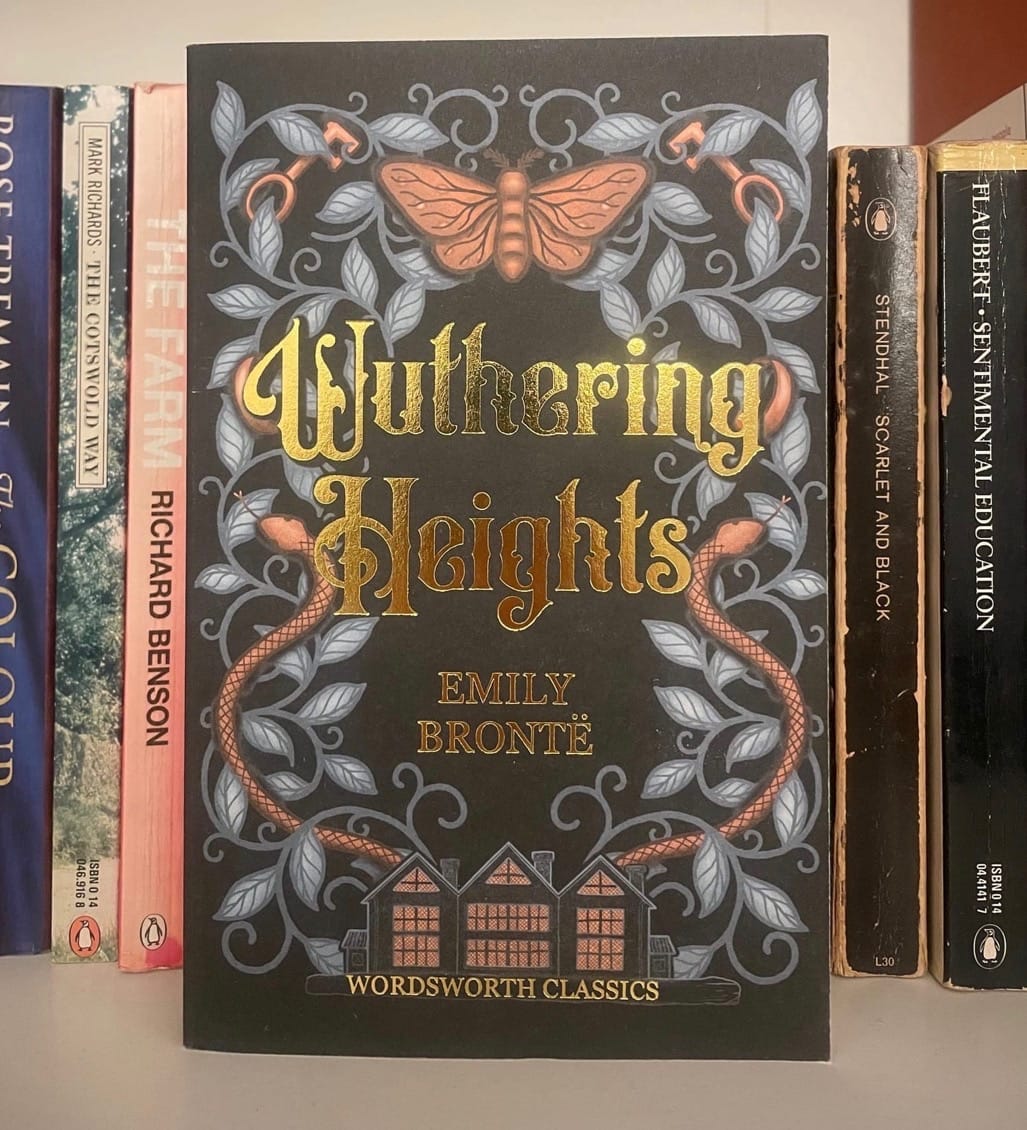

Despite this, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (one of my personal favourites) explores highly universal themes of class, love and revenge. These themes are undeniably relevant today, however, in different ways. Socially strategic marriages still occur, yet in more obscure terms, and maybe you know someone who dedicated their life as solely to revenge like Heathcliff, but I definitely don’t. These stories become more improbable as we move further away from the publication date, but it is the themes and raw representation of the human condition that remains relatable.

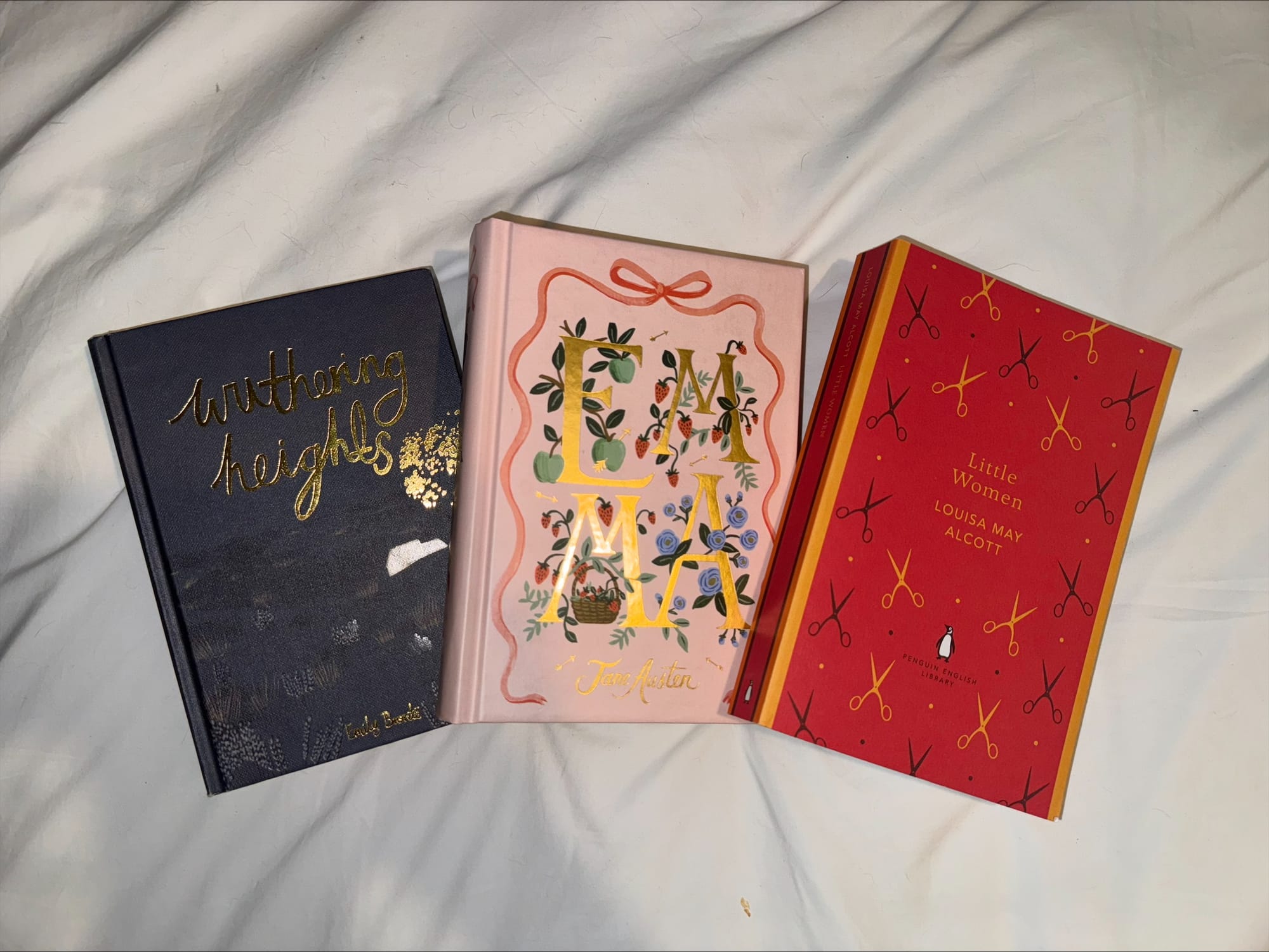

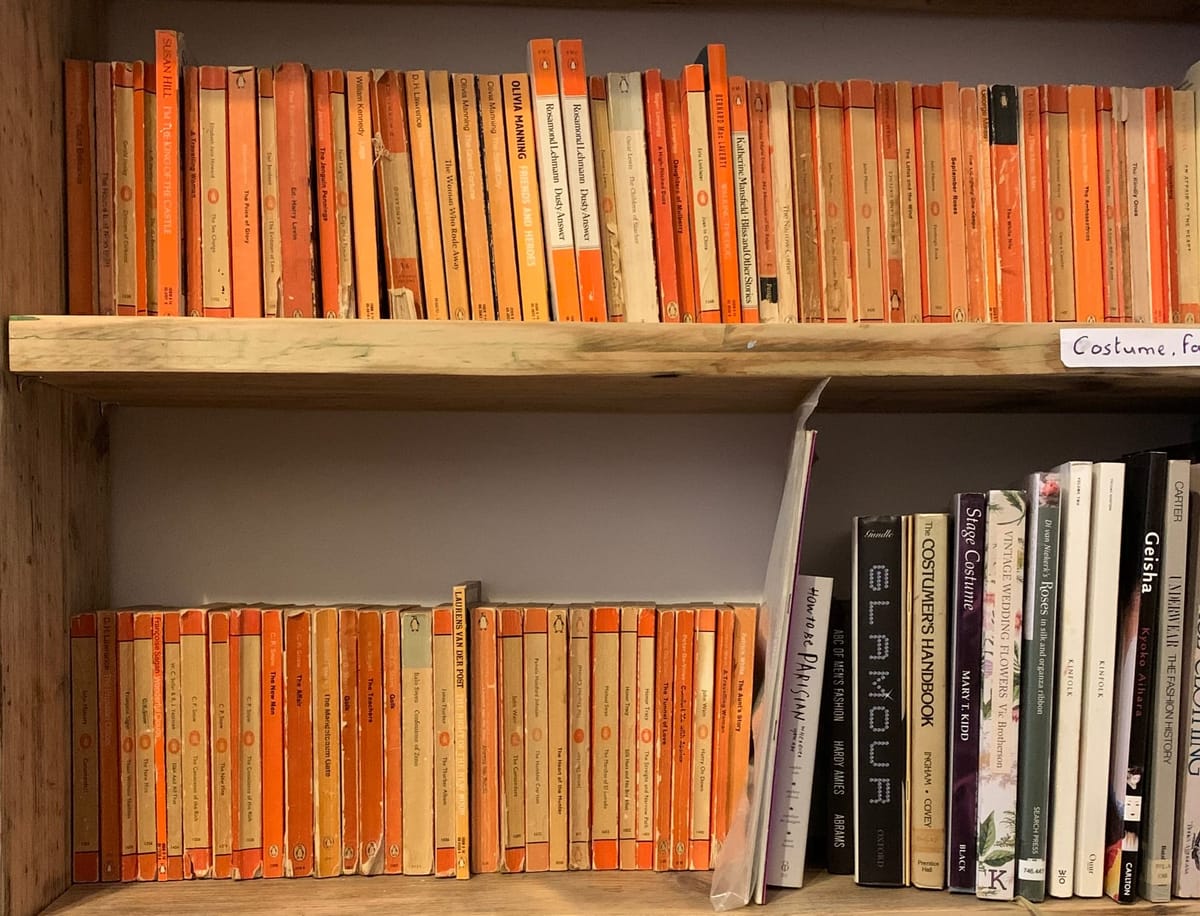

There is also the problem of the performative reader of classic novels. I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel pretty aesthetic as I read my hardback, limited edition of copy of Emma in public. These books now hold such an intellectual status it is inevitable people may now read them just to say they’ve read them. I remember coming to university feeling insanely worried I wasn’t well read enough in the ‘classics’ and spending the summer before skim reading as many as I could before starting. The ‘classic’ label does more harm than good in this respect because I genuinely believe few people read these books for the story and morals anymore. I was surprised to find less of the ‘classics’ on the Bristol English syllabus than I expected (and quietly relieved), but this is a large change from what studying literature at university used to look like.

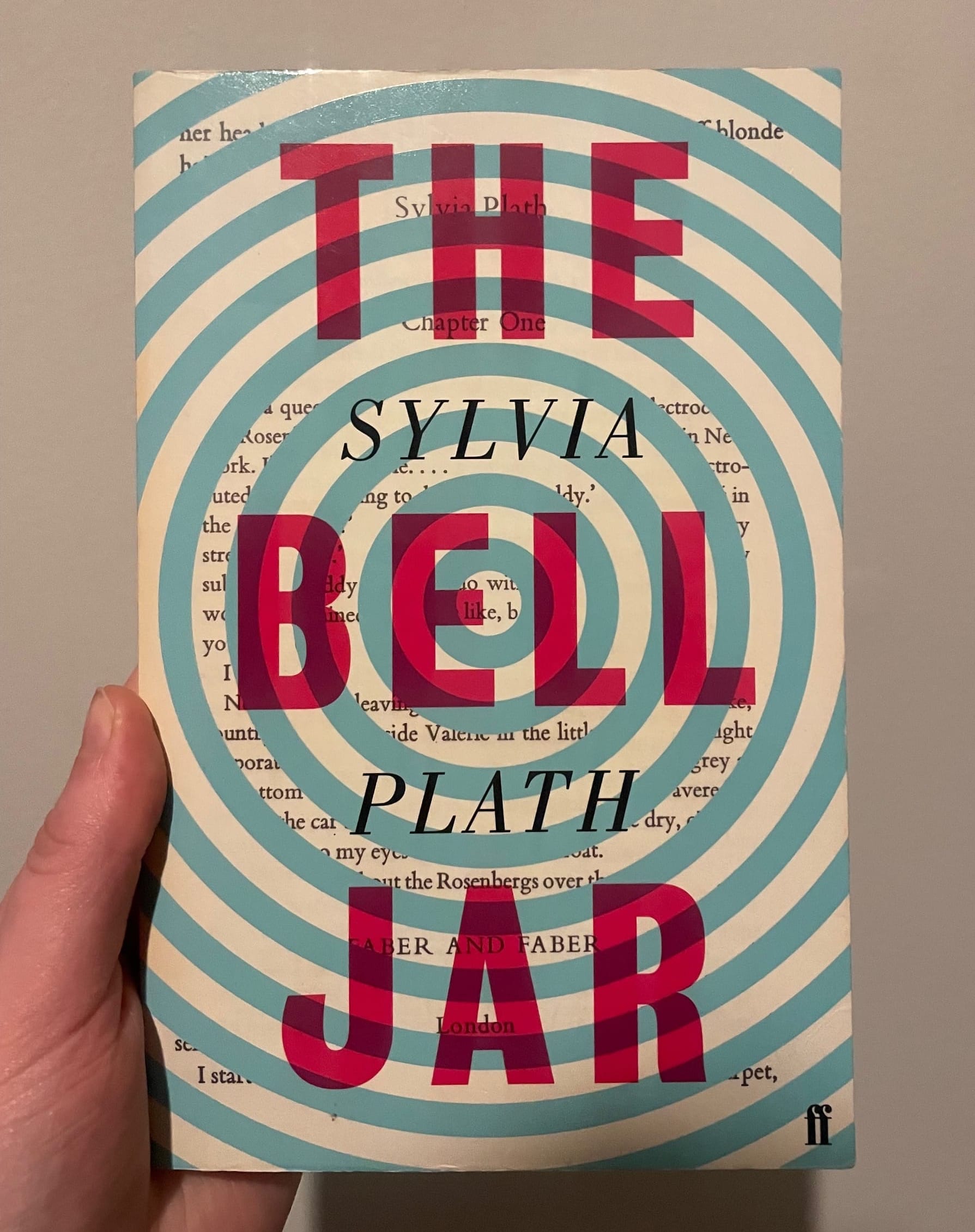

Some further modern dilemmas with reading classic books are the lack of representation, allusions and references now being lost on us making the books quite difficult reads, and the emergence of modern classics. Let’s face it, most classic are written by dead white men. Female authors of classics are sparse and classics by people of colour are fewer – as a result they feel outdated and unrepresentative. More and more books are being discovered by a wider scope of people, but it is still not enough to feel inclusive. Many references to events of the time and allusions to other authors are also missed as we have sadly forgotten them – we cannot gain as much from reading these books as a past society would have. And finally we have the controversial genre of modern classics with books like Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. This complicates the very idea of a classic having to withstand the test of time, obscuring the already grey genre of the classic novel.

Overall, we have become so obsessed with the concept of reading the ‘classics’ that the true magic of them is getting lost. Many of these books are timeless and should continue to be read, but not for the reason of aestheticism and with the addition of the rediscovery of lost treasures from a wider demographic of authors.

Featured Image: Epigram/ Emma Coleman

Do you think reading the classics has become performative?