By Ellie Brown, News Subeditor

Free Solo (2018), documentary. Love, Actually (2003), romantic comedy. The Hobbit Trilogy (2012-2014), fantasy and action adventure. What do these films and genres have in common? Answer: not many people would call them political.

It’s easy to see why. Politics, referring to the activities of elected bodies in remote places like Westminster or the SU, is not that compelling a topic for these kinds of movies. Free Solo, is interesting because it focuses on the personal life and ambitious undertaking of a climber – something that, unlike politics, isn’t constantly part of the news cycle.

Love, Actually is similarly constrained by its genre. Though it does feature a Prime Minister, the film is more invested in his relationship with Natalie, the tea lady, over his ability to run the country. After all, she, rather than economic or strategic concerns, is the reason the PM finally stands up to the U.S.!

And finally, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), like many fantasy and action-adventure films, entertains its audience by being an escape from normal life; we are transported to a different universe - Middle Earth - and follow the quest of a few rogue characters. So, it’s about as far from the dull processes of governing and elections as you can get.

However, I don’t think this is the whole story.

First, let’s look at the definition of political we’re using. Is this the only way the word is used in everyday life? No. According to both academics and favourite internet source Wiktionary, politics can also mean ‘social relationships that involve power or authority.’ Think of the terms ‘office politics’ or ‘sexual politics’ and you’ll know what I mean. Politics does not just take place in the official locations we are told about; it permeates every aspect of our lives, whether we know it or not.

"A movie isn't a political movement, a party or even an article. It's just a film. At best it can add its voice to public outrage." #KenLoach @SWMYFilm #SorryWeMissedYou Now Playing #GigEconomy @Guardian 'Picture Politics' https://t.co/AAXimJ21u5 Tickets: https://t.co/UlMczocHc0 pic.twitter.com/FLtCaCNhSY

— The Electric Cinema (@ElectricBham) November 16, 2019

Because of this, the above films can be understood as portraying politics in some sense of the word. Most clearly, this shown explicitly as conflict and its resolution between characters, such as the struggle over Smaug’s gold in The Hobbit.

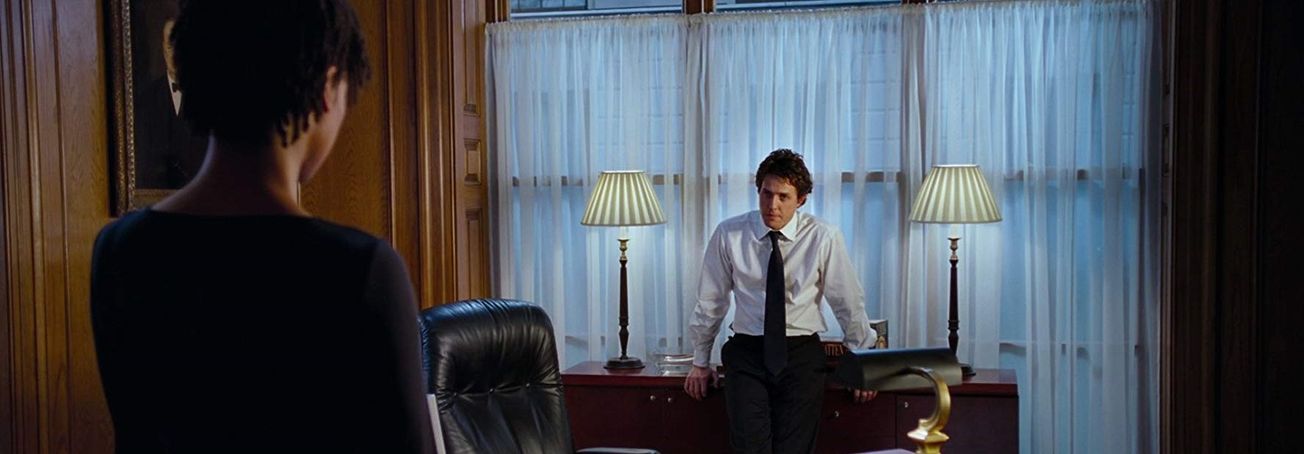

However, explicit conflict between characters does not need to exist for there to be power relations between them. Take Love, Actually, for example. It’s no coincidence that Hugh Grant’s Prime Minister is a straight, white man from presumably an upper-class or certainly highly educated background; these characteristics have given him the advantages needed to gain the ultimate position of power in the country. Meanwhile, Natalie the tea lady – and various other female characters in the film – are the ones who take on the domestic and emotional division of labour.

Think of the terms ‘office politics’ or ‘sexual politics’ and you’ll know what I mean

Likewise, in Free Solo, the ability of Alex to climb wild areas in the U.S. also depends on a particular socio-economic context and the balance of power this entails. Alex makes enough money to live from his talents, yet these depend on an entire industry of sponsorship deals, widespread social media usage, and a capitalist economy which allows Alex to meet other basic needs using the money he has earned from his fame and talents.

| Can cinema ever be truly apolitical?

As well as portraying politics on-screen, films play a political role in social life which also cannot be ignored. Films do not have to be explicitly linked to political parties or social movements to do this; even movies in the above genres, which are supposedly neutral, have some impact on power relations.

By not questioning the power relations that are shown, the films arguably normalise them and encourage their reproduction in the lives of the audiences watching. While not every viewer of Free Solo will go and climb a mountain, or of The Hobbit start pointless wars over money, or even of Love, Actually immediately confess their love to their best friend’s partner, the choice of subjects encourages viewers not to question the political orthodoxies which make up the societies they live in.

Films play a political role in social life which also cannot be ignored

As well as this, film-making can affect and is affected by politics in both senses of the word. For example, the making of The Hobbit films led to new labour laws in New Zealand which affected the ability of workers on films to unionize. The #MeToo scandal showed how gender left female actresses vulnerable to the predatory behaviour of high-powered males on film sets, prompting a widespread shift in attitudes to gender relations.

| Ken Loach: The king of the political drama

Finally, in the UK, a great range of film subjects is allowed. and the consumption of films is regulated by only a few laws; this contrasts with more politically repressive states, such as North Korea, where the balance of power depends on these activities being highly regulated.

For these reasons, films cannot avoid being political in the wider sense of the word. Arguing that films can be apolitical ignores these links and may perpetuate existing configurations of power. Their subjects always have a political dimension and film-making is affected by, and has a role in shaping its political context.

Featured: IMDb / Universal Pictures

Do you agree that cinema can never be free from politics?