By River Korkmaz, First Year, Film and Television and Lily Scogings, First Year, Film and Television

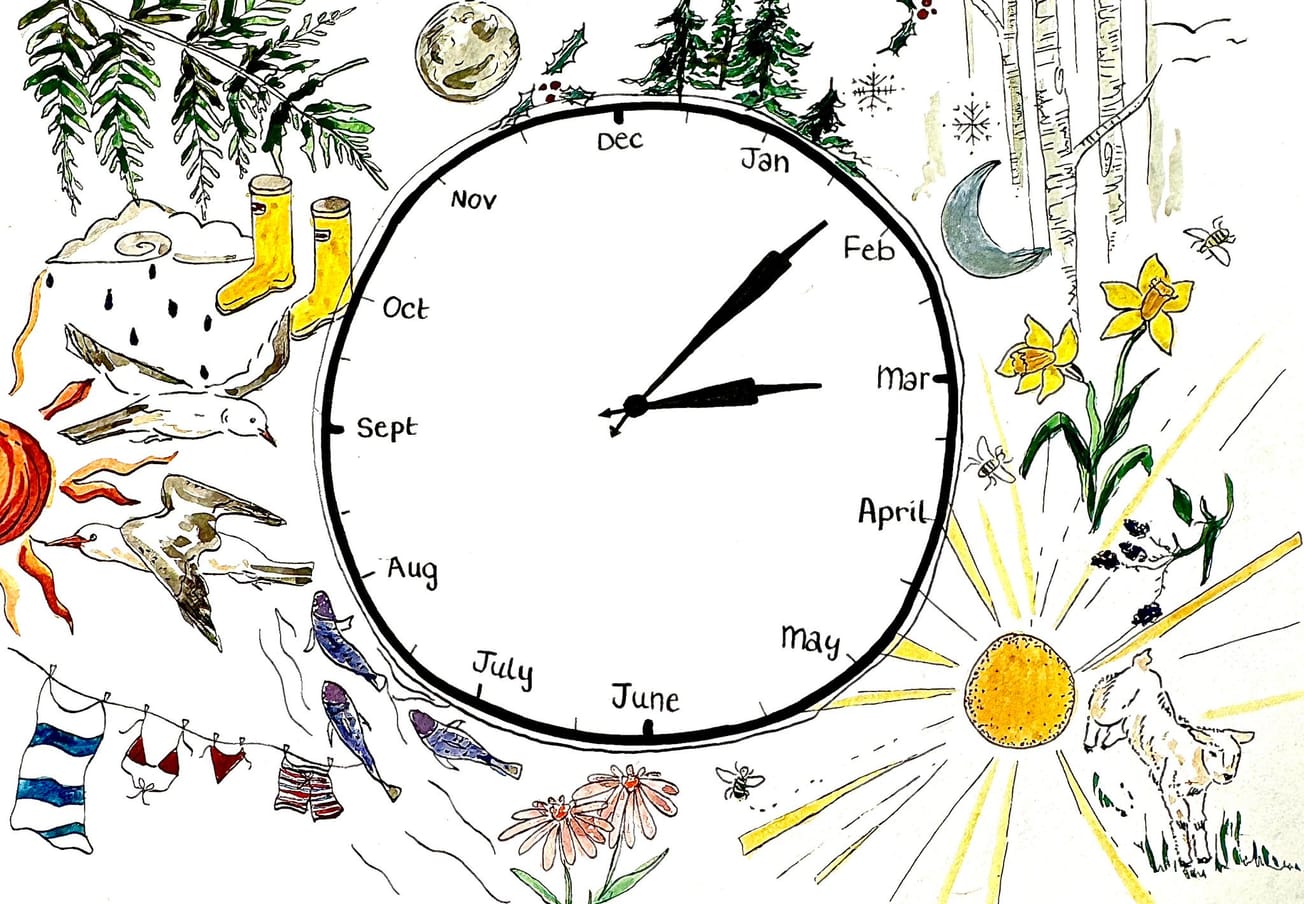

The Encounters Film Festival in Bristol is aptly named. Since its founding in 1995 as a short film showcase, the festival has built its reputation on enabling precisely that: encounters between audiences and artists, between cinema’s past and its futures, between films and the shifting frameworks of interpretation that surround them. A festival of scale yet intimacy, Encounters has consistently been a crucible for both emergent voices and established auteurs. Over the years, its stages have hosted animators like Hayao Miyazaki, alongside early works by directors who would later become household names.

This year, one of the most anticipated encounters was a retrospective screening of the cult film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), followed by a conversation with its writer Charlie Kaufman and director Michel Gondry. That the event took place in Bristol felt particularly significant: a city whose cultural venues — most notably the recently renamed Bristol Beacon, formerly Colston Hall — have long been sites of artistic innovation. Once associated with Edward Colston, a figure tied to the transatlantic slave trade, the hall’s re-christening marked a symbolic act of redefinition, aligning the venue with values of inclusivity and renewal. Over the decades, it has hosted performances by The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, and Bob Marley, situating Bristol as a nexus of experimentation and communal discovery. In this lineage, Encounters does not stand apart but carries it forward, translating the vitality of live performance into the language of cinema.

It is the opening night of Encounters Film Festival’s 30th Edition, a film festival that has grown from a small short film event in the 90s to one of the UK’s key exhibitions of rising creative innovators. Recognised by BAFTA, BIFA and the European Film Awards, Encounters festival is renowned, but its real strength lies beyond accolades and in the vibrant, communal spirit it cultivates; for the university community and the city’s vibrant arts scene the festival is a cornerstone for celebrating the art of cinema itself, whilst amplifying new talent and nurturing connections between industry professionals and young filmmakers. The space tightens as the audience finally settles, the last murmurs fading as the lights dim further, a brief stillness renders the room silent as the audience fixes its eyes forward.

The event underscored the enduring significance of Kaufman and Gondry’s collaboration whilst also showcasing the evolution of their work as artists and what directions they have since followed. Kaufman’s recent short, How To Shoot A Ghost (2025), and Gondry’s latest feature, Maya Give Me A Title (2024) illustrate both their distinctive styles that have long defined their work, whilst charting new artistic territories. On stage with Anna Higgs' moderation, the discussion offered insights into their creative processes; Kaufman, in one instance, revealed that he had once rewritten a small section of the film within a few hours of a single day while seated in a hotel, an anecdote that illuminates the meticulous care behind the film’s narrative complexity. He also reflected upon the myriad of endings he considered, exemplifying the interplay between intuitive precision and meticulous craftsmanship that he has artfully underpinned in his work:

“I had so many different ideas for the ending,” Kaufman mused “... and I didn’t always know what they meant. In the end I just went with the one that felt most true to the story”

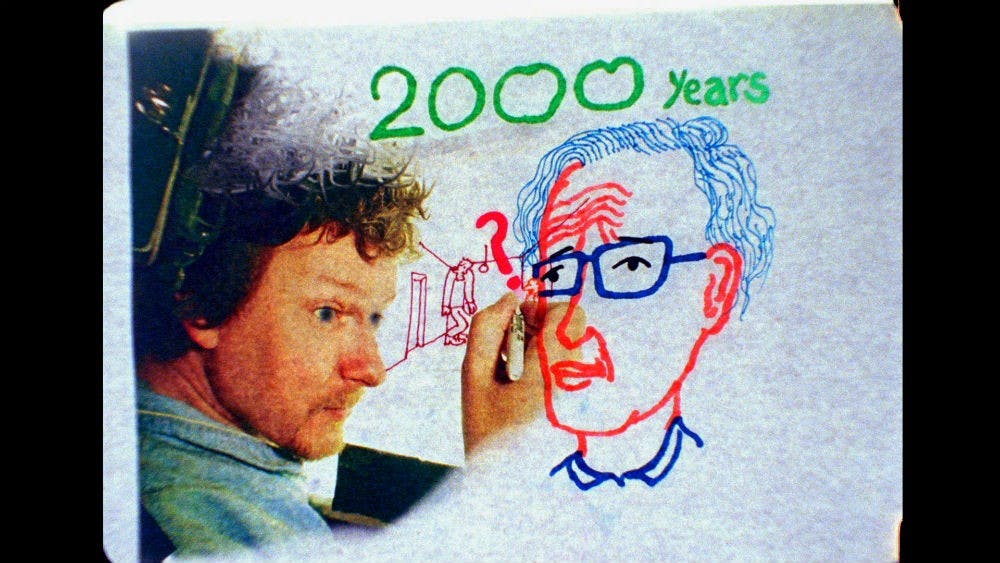

Kaufman spoke with characteristic reticence, his responses marked by hesitation and recursive qualification — a discursive style mirroring the self-effacing uncertainty that permeates his screenwriting. Reflecting on the film’s conclusion, he admitted, “I don’t really know what it means, except that it feels true to me,” a remark that underscored his investment in affective resonance over definitive interpretation. Gondry, by contrast, embodied a kinetic exuberance: his gestures animated his commentary as he detailed the analogue ingenuity of his visual practice. His anecdote about staging the vanishing bookshop scene through rapid costume changes rather than digital compositing drew laughter, reminding the audience that his surrealism is always anchored in material craft and practical effects. Perhaps most telling was Gondry’s unabashed admiration for Kaufman, confessing that after Eternal Sunshine he found it difficult to collaborate with other writers, their scripts lacking the same density of melancholy and emotional acuity. Their dynamic was not simply professional but almost symbiotic — Kaufman’s cerebral melancholy animated through Gondry’s playful invention.

Revisiting Eternal Sunshine in 2025 also illuminates the cultural baggage the film has acquired. Released before the term manic pixie dream girl (MPDG) entered mainstream discourse, Clementine, played by Kate Winslet, has frequently been swept into this lineage. Yet feminist criticism emphasises that this reading risks flattening her into a stereotype the film actively resists. Clementine is not an object designed to facilitate Joel’s (Jim Carrey) transformation; the narrative exposes the danger of such projection. Her flaws, volatility, and autonomy are central. “Too many guys think I’m a concept,” she protests, “or I complete them, or I’m going to make them alive. But I’m just a fucked-up girl who’s lookin’ for my own peace of mind.”

Kaufman’s script and Gondry’s direction insist on Clementine’s complexity, showing how memory, desire, and narrative can trap women in roles men assign them. Clementine can now be misread as a stereotype precisely because the concept has been codified after the film’s release. In this sense, films are never stable; they exist in dialogue with evolving cultural criticism and audience reception.

The conversation also touched upon broader themes in Eternal Sunshine, especially within the preoccupation in which the film coarsely interrogates the complex ordeal of human nature and memory, forcing the viewer to locate their interpersonal memories of loss and recollection, rendering them tangibly real for a brief moment. Gondry reflected upon the idiosyncrasies of his creative process, remarking that his struggle with insomnia often resulted in extended sessions late throughout the night sketching and refining his visual experimentation:

“I would get bored just lying there,” he stated, “... so instead I would just draw, sometimes all night, imagining how the film could look and sketching it out.”

These nocturnal sketching sessions, born out of restlessness, proved foundational to the shaping of the film’s visual composition; a feature that resonates powerfully with audiences as the film’s cinematography transforms visual beauty into a vessel for nostalgia and connection. This attention to visual detail is consistent throughout the film, from Clementine’s perpetual shifting of hairstyles and wardrobe, which highlight her ever-changing state of mind, to the tonal ambiguity of the film that oscillates between melancholy and hope, mirroring the fragile state and the resilience of the human experience.

Encounters makes cinema a relational event: a negotiation between text and audience, auteur and interpreter, historical moment and contemporary re-reading. Kaufman’s self-reflection and Gondry’s exuberance served not merely as paratextual supplements but as active agents of re-signification, reframing the film in real time. Clementine remains compelling because she resists closure, her volatility refusing the stabilising function of stereotype.

As the event finally drew to a close, the lingering of the persisting and enduring relevance of Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman’s artistry, but also the sense of Encounters itself as a space where such dialogues can thrive. Balancing retrospection with innovation, the festival embodies the very qualities it evokes, serving as a reminder of why, 30 years later, it continues to matter.

Featured Image: Epigram/ River Korkmaz

Did you manage to catch a glimpse of the Encounters Film Festival this year?