By Lucas Mockeridge, SciTech Deputy Editor

A flamboyant, swashbuckling engineer, Brunel was one of the best that Britain has ever produced. His influence on Bristol remains strong, 180 years after his SS Great Britain first floated out into the harbour.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel is hard to escape from in Bristol. His name adorns everything from maritime museums to Indian restaurants. But Brunel was born in Portsmouth in 1806, and called London home. So why does Bristol regard him as one of her own? To find out, I sat down with Tim Bryan FMA, Director of the Brunel Institute at the SS Great Britain Trust.

‘Brunel plays a really key role in the 19th century history of the city in terms of communications, in terms of raising the profile of the city,’ Mr Bryan tells me. ‘Bristol was the place where Brunel's career was really launched’.

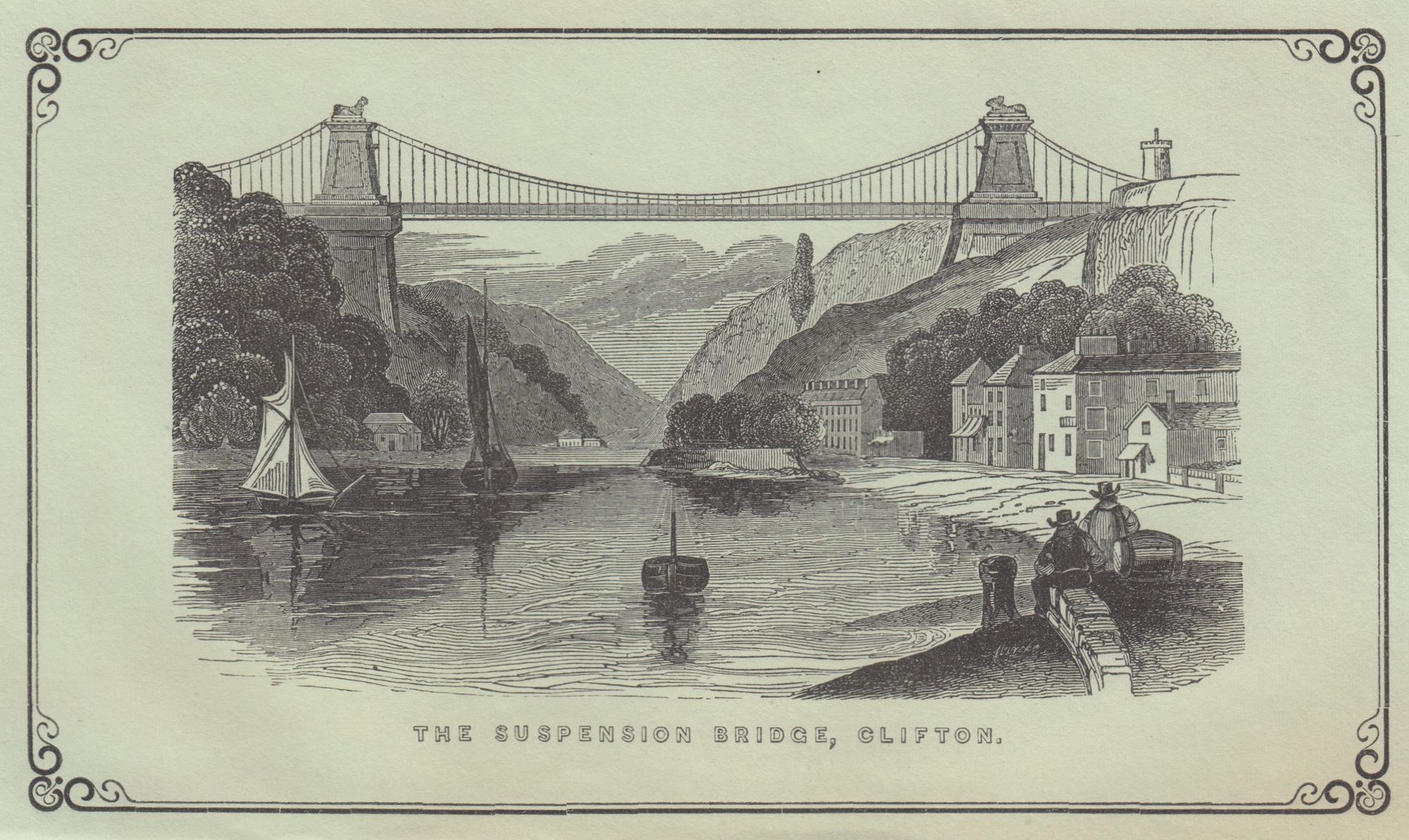

The Clifton Suspension Bridge was Brunel’s first project of his own. It was finished as a memorial to him after his death in 1859. ‘People say it's Brunel’s design; it’s based on Brunel’s design,’ explains Mr Bryan. ‘He wanted a very grand design with an Egyptian style’.

Through his work on the bridge, Brunel befriended a group of Bristolian merchants. They commissioned him to create several daring feats of engineering in the hope of changing the city’s mercantile fortunes.

Bristol had lost its place as Britain’s second port to Liverpool, after failing to diversify its trade, neglecting its docks, and levying extortionate dues. ‘The world had changed; Bristol maybe had not changed with it,’ notes Mr Bryan.

To keep up with Liverpool, Bristol needed its own railway line to London, and Brunel was tasked with designing it. After opening in 1841, the Great Western Railway was the fastest in the world, and the first conceived as a complete system. Brunel had cut the journey from London to Bristol from twelve hours to four, and spared travellers from the teeth-jarring stagecoach.

Brunel attributed his railway’s smooth ride and astonishing speed to his novel track. He had set the track rails apart to his broad gauge of 7 ft, instead of the standard gauge of 4 ft 8 ½ ins. Brunel saw that a wider track would allow the carriage to go between the wheels. He could then use larger wheels to reduce friction, whilst still retaining a low centre of gravity for the body.

The broad gauge upset the engineering establishment, who wanted one gauge throughout the country. Otherwise, passengers and goods had to change carriages when the two gauges met. As a result, Brunel’s broad gauge was eventually scrapped in 1892. ‘He always wanted to do what he thought was the best,’ says Mr Bryan, ‘even if his critics and shareholders disagreed with him!’.

Whilst working on the Great Western Railway, Brunel was also designing the SS Great Western. He envisioned passengers travelling to Bristol on his railway and then boarding his steamship to cross the Atlantic. Brunel was told that transatlantic steam navigation was impossible, as a larger hull to carry the coal for the journey would itself require more coal.

But Brunel knew that the volume of the hull increased as a cube of its dimensions, while the surface area increased as a square. There was therefore room for both coal and cargo. In 1838, Brunel was vindicated when the SS Great Western, the largest passenger ship in the world, steamed across the Atlantic in 16 days. The journey would have taken up to six weeks by sail.

Brunel was then commissioned to build a sister ship. Instead, he built an even bigger vessel, the SS Great Britain. With her metal hull and screw propeller, she was the first modern ship. The SS Great Britain was launched in 1843. Tens of thousands of excited Bristolians gathered to watch, and the church bells rang constantly.

However, the SS Great Britain was too wide to leave the harbour. By the time the harbour had been modified, the Liverpudlians had rapidly expanded their own fleet of transatlantic steamers. The SS Great Western had already been driven to Liverpool by exorbitant dock dues, and the SS Great Britain was too big to work from Bristol. The city’s transatlantic dream was over.

After 90 years and more than a million miles at sea, the SS Great Britain was left to rot in the Falkland Islands. In 1970, she was towed across the Atlantic on a giant floating pontoon, after £150,000 had been raised to save her. 100,000 people lined the banks of the River Avon to welcome her home. She now sits in the same dock whence she was launched 180 years ago.

‘We're telling new stories all the time,’ says Mr Bryan. ‘We're looking at the story of the people who travelled on the ship’. One of those stories was that of the first English cricket team to tour Australia. The SS Great Britain is so large that the team were able to practise on deck.

Even from the grave, Brunel is still shaping Bristol. The SS Great Britain has given an identity to the harbourside, and is the city’s number one tourist attraction. Brunel was a man who shrank the world. His railways brought the country to the city; his steamships, the Old World to the New. And Bristol was where they were made.

To learn more about the SS Great Britain, visit www.ssgreatbritain.org.

Tim Bryan’s new book Iron, Stone, and Steam: Brunel’s Railway Empire is out in November.

What do you think about Brunel's legacy in Bristol?