By Benji Chapman, Co-Deputy Music Editor

Not long ago, ADHD was believed to be a condition which only affected children, through restlessness, fidgeting and a lack of discipline. However, as our understanding of the condition has developed, we are learning not only that it affects adults, but that it manifests in a myriad of ways.

Accompanying this enhanced understanding of the nature of the condition is an exponential increase in diagnoses.

Understanding ADHD is complex: not only are there misconceptions that skew our perception of the condition, but its definition is constantly changing.

How is the ADHD medication shortage in the UK affecting people? https://t.co/GcEqQ89Trn

— BBC News (UK) (@BBCNews) October 6, 2023

In 1968, what we now know to be ADHD was initially defined as the ‘Hyperkinetic reaction of childhood’. The second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) described the common attributes of the condition: ‘Overactivity, restlessness, distractibility and a short attention span.’

In 1980, the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) coined the term ‘Attention Deficit Disorder’ (ADD) to describe the condition. In 1987, this terminology was revised to ‘Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’. The condition was split into three sub-types: impulsive, inattentive and combined type — the latter being a combination of both impulsive and inattentive behavioural characteristics and the most diagnosed type of ADHD.

The evolution of these definitions of attention deficits has gradually encompassed more types of behaviours: moving from physical hyperactivity, towards cognitive hyperactivity and, more recently, a version of the condition which recognises non-hyperactive behaviour as equally emblematic of an attention deficit.

‘As much as I think people talking about mental health is very good [...] There are some instances in which it can lead people to think that any kind of difficulty needs to be pathologized’

By the nature of our ever-changing understanding of neurodivergence, it's no surprise that people are just beginning to believe that the condition isn't as simple as physical hyperactivity among children and can present itself in many ways.

As we continue to research attention deficits, it is clear that finding a singular definition for variances of hyperactive, inattentive and impulsive behaviours is challenging.

The diverse presentation of behavioural patterns often leads to overlapping symptoms with other neurodivergences, like Autism and Dyslexia.

Book excerpt: ADHD has become an identity, not just a disorder. We need a new way to talk about it https://t.co/tcNJDmiUcH

— anthropologyworks (@anthroworks) September 21, 2023

According to the University of Bristol, 3-5% of the UK’s population have an ADHD diagnosis. Dr Tony Lloyd, the chief executive of the ADHD Foundation, said that their figures suggested there had been a 400% increase in the number of adults seeking ADHD diagnosis since 2020.

In 2023, Jane Sedgwick-Müller, a senior teaching fellow and expert in ADHD in university students, said that there had been a sharp increase in the number of university students seeking a diagnosis.

Epigram spoke to three students diagnosed with ADHD to learn about their experiences and the common misconceptions people have about the condition.

Speaking to Epigram, one third-year student — who wished to remain anonymous — said: ‘As much as I think people talking about mental health is very good [...] There are some instances in which it can lead people to think that any kind of difficulty needs to be pathologized.’

The student went on to say that ‘If it's really affecting your life and making your life difficult on a day to day basis, or on a regular basis, and it doesn't go away, then look into it’.

Promoting a positive discussion about pursuing a diagnosis for neurodivergence is a good thing. However, it can become murky territory when there are already so many misconceptions, both historic and current, about the condition.

All three students who spoke to Epigram remarked that they had encountered a common misconception from non-ADHD individuals: ‘You can't have ADHD if you're academic.’

They noted that this was felt particularly by women and girls with ADHD, who have arguably become more used to masking and internalising inattentive behaviour as a response to learned social patterns and stimuli.

‘You get so many idiots who view [ADHD medication] as a study drug. It doesn't help that ADHD is already stigmatised’

The age-old trope that attention deficits only affect hyperactive young boys leads to the continuation of antiquated stereotypes about the condition which consequently makes it a more difficult topic for women to broach. Thankfully, however, the trend is gradually being challenged as we discuss ADHD more as a society.

In discussing another common reaction to telling people you have ADHD, one student said ‘When I tell most people I have ADHD, they'll respond with something like “Oh I think I have that” [...] although they don’t necessarily mean to, it kind of minimises what I'm talking about and the condition itself’.

The students reasoned that pursuing a diagnosis should be encouraged, but not relied on to feel validated in your struggles.

One student said: ‘You can't always be happy and productive and cheerful all the time — you’re a person, not a robot. ‘Just because something is a challenge doesn't mean it's necessarily to do with ADHD’, another agreed.

It's vital that we realise everyone, neurodivergent or not, goes through struggles. If we recognise that everyone goes through low points, we can move forward with our approach towards mental health that is unified and inclusive.

The students concluded that the point at which symptoms of ADHD become a persistent and long-term problem is when one should seek a diagnosis.

I have driven for almost three hours to Wales to the ONLY place in hundreds of miles to stock my ADHD medication currently, and it's packed and there's a 2 hour queue.

— 🌊 Silvy 🏳️⚧️ (@SilvyLoog) February 16, 2024

I did this because I had a MENTAL BREAKDOWN this morning

We have to do something about the #ADHD med shortage pic.twitter.com/KPaBMjkVPO

One student speculated that the recent reported shortage of ADHD medication may be because more students are turning to them to aid their university studies.

They went on to say: ‘You get so many idiots who view [ADHD medication] as a study drug. It doesn't help that ADHD is already stigmatised.’

Depriving people with ADHD of medication can be harmful. For instance, another student mentioned how the effects of unmedicated ADHD lead to an overwhelming sense of disorganisation in their everyday life, with tasks like cleaning dishes and clothes eventually leading to burnout: ‘At the worst of my disorganisation I was wearing the same clothes for weeks’.

‘I just don't want to ever work without them’ | Pro plus, Elevense and Adderall: The use of study drugs at UoB

‘It’s troubling seeing the quality of life that often comes after you graduate’ | The reality of being a medical student

Discussing how they have come to embrace their condition, one student said that ‘Something which has helped me personally post-diagnosis is marrying a feeling that while I am affected by my ADHD; not everything I do is related to, or as a result, of it.

‘During my diagnosis, I had to reconcile whether I wanted to be medically labelled as someone with a ‘Condition’ - one which I couldn’t erase. However, having met the wonderful, forward-thinking people at university that I have, I now know that ADHD isn't something to be ashamed of.’

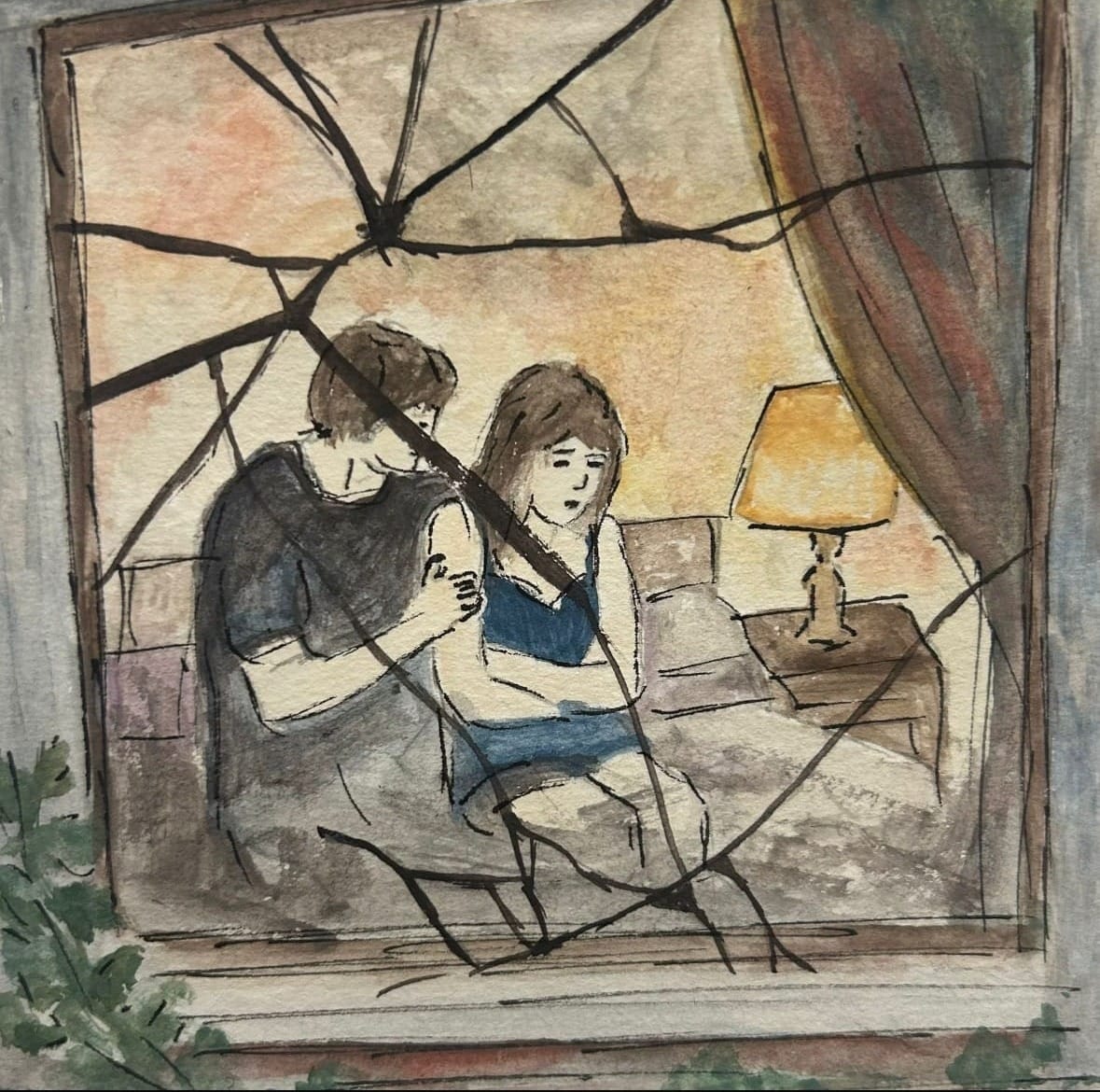

Featured Image: Epigram / Dan Hutton