By Tylah Hendrickson, Arts Subeditor 25/26

As our communication has increasingly become digitalised, phrases have become shorter and the pace of words being produced has accelerated massively. Like many other things, language has been put into a trend cycle, to be consumed, enjoyed, and replaced.

This is not unheard of. Words and meaning are constantly woven to reflect shifts in society, culture, and more recently our relationship with technology.

Phrases easily become dated and expressions from hundreds of years ago have been entirely eliminated from our language. For example, 15th century writers like Chaucer and Shakespeare are probably only halfway intelligible, and old English is almost unrecognisable compared to the modern English spoken today. But some stick, we still use words that Shakespeare coined and popularised in our regular speech (like ‘gossip’, 'rant’ and ‘eyeball’ – he’s a genius for this one).

But those words kind of make sense right? Their longevity feels justified compared to words like ‘cooked’ and ‘based’ breaching into casual face-to-face conversations outside of their original online spheres. Maybe we don’t take internet-born phrases as seriously as literature that's been documented over hundreds of years. We don’t, and I’ll tell you exactly why that is.

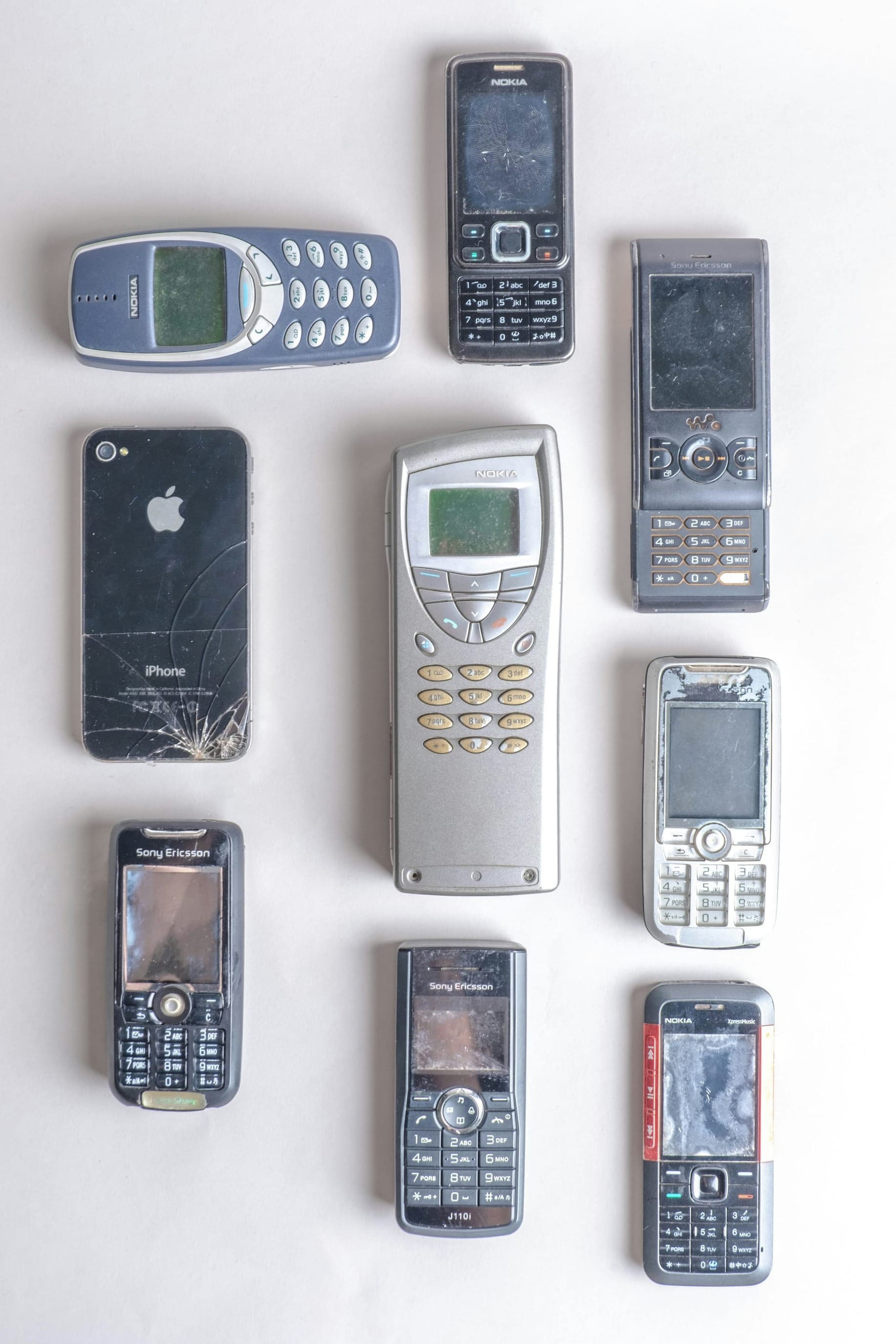

Thou and thee, to a simple ‘u’

The first SMS message was sent on December 3 1992 (according to google) and sparked a new world of digital chat rooms like Myspace and MSN messenger. From there the quirks multiplied. Emojis reached widespread popularity in the 2010s, despite being first created in Japan in the late '90s. These inclusions added depth and nuance to digital communication, marking a shift from formal to a ‘keyboard casual’ era of expression. Early acronyms reduced sentences to compact signals and as video content became more popularised, the digital accent of ‘algospeak’ (‘algo’ meaning algorithm –a form of rhythmic uptalk, distinctly Californian in nature) emerged as content creators began reshaping language to avoid moderation filters.

Over the past five years, vertical forms of entertainment have eaten up our attention spans, bones and all (I blame lockdown, RIP YouTube). It’s easy, accessible, and before you know it you’re doom scrolling in bed with your consciousness being dominated by the phone in your hand, mindlessly swiping while you don’t process a single thing that's right in front of you.

How is this relevant to language? Previously upheld eloquence has been replaced by efficiency and exposure, online content only amplifies this: whatever’s ‘cool’ or trendy leads change, and trends get pushed by algorithms.

As words are easy to borrow, certain terms and phrases can very easily get pushed into linguistic normality the same way.

'Historically, [...] young people, working-class communities, Black people, women and queer people have been innovators for expressions that eventually filter into the mainstream'

Of course, this isn’t just about nonsense syllables. In sociolinguistics, it’s long been observed that people with covert prestige facilitate changes in language (influence rooted in ‘cultural cool’ rather than institutional authority). Most change happens from the bottom-up in culture. Historically, that’s meant young people, working-class communities, Black people, women and queer people have been innovators for expressions that eventually filter into the mainstream. For example, words like ‘gag’ and ‘clock it’ began in black and queer spaces before becoming online staples.

‘Skibidi’ and ‘rizz’ phonetically just sound funny, these types of words are typically interjection and intensifier words that are flexible in meaning, and sometimes used as nonsense filler terms.

Many people on social media see this shift in language as detrimental, often blaming younger generations' consumption of absurd content for a broader cultural decline – amplified by fears around AI and shrinking attention spans (which are completely valid). When I went home for the summer and saw that my five year old sister had a Labubu on her school bag, admittedly I briefly cussed out Dubai and Elon Musk. But in a weird way, this language does serve a purpose in creating a sense of community – we consume and push absurd content because it’s ironic, and algorithms reward our engagement with it.

We giggle at the silly words on our screens as they slowly creep their way into our everyday lexicon. Meaning has easily been compressed, sometimes simplified, and occasionally flattened in the rat race to consume attention.

'This linguistic shift reflects a larger cultural prioritisation on immediacy'

This linguistic shift reflects a larger cultural prioritisation on immediacy that has reshaped not only language, but the arts and communication more broadly. As a species evolved for face-to-face conversation, our linguistic shifts are now created digitally through audio rather than direct interaction.

It’s not necessarily rotting our brains and the future generations, it’s just a new form of language change that reflects the general passivity and speed of our contemporary society.

Whether ‘aura farming’ makes it into the Oxford English Dictionary in 100 years will depend on whether we keep saying it until it loses all meaning, which might be the most fitting fate of all in the algorithmic age.

Featured Image: Epigram / Tylah Hendrickson

How often do you use the language of 'brain rot'?