By Corin Hadley, SciTech Editor

The blunder

‘… yeah but Corin’s a bit …’

Huh? Say that again? I let my head follow my spinning vision and whip around. I’m back in The Berkeley. A number of double tequila lime sodas too deep again. Someone just whispered some absolute slander about Corin (that’s me) literally in my ear - but there’s no one there.

Instead, across the room between the swaying, swaggering students I pick out a pair of guilty eyes flicking away from mine. My chemistry opp - my name hanging incriminatingly from their lips.

How come, despite being well and truly out of earshot, I could hear that which I should not have?

The Wetherspoon's website didn’t tell me much, just a mention that the popular watering hole had once been a café. The writing on the glass - ‘whispering gallery’ - gave me a lead. I’d seen someone on LinkedIn complaining about the council decreasing the open hours of the city archives – maybe they’d be able to help.

The archivists

In an email, I gave over the info I had (that is - essentially just a question) and name-dropped Epigram to try score some credibility points.

The archivists did not disappoint. The building the Berkeley now inhabits was created around 1924, when the three buildings between 15 and 19 Queens Road were fused into the Messrs Cadena Café. This post-war pleasure palace was renovated significantly, unifying the three buildings into a Park-Street-top beacon of 20th century luxuries. In the café area, I was told, this elegant dome might have been the centrepiece.

The email also mentioned that I could pop in, for free, without an appointment, to dig through the original drawings. How is that a thing you can do for free? I couldn’t say no.

The archivists had been right.

The plans showed that the dome would’ve covered the central café area in the arcade, now the nook of booths around the corner. The dome certainly took centre stage, but how had it been designed with acoustics in mind? I still didn’t know how you'd make it do that, or whether people even knew about acoustics in the 1920s.

Whispering waves

They did.

In the 1870s, the (literal) height of cool for a London bourgeoise hangout was to go and chat shit in the upper gallery of St Paul’s Cathedral. The Nobel prize winning physicist Lord Rayleigh was on this scene, and when he had a similar experience to mine in the Berkeley, he neeked out. This man wrote a whole paper on his new discovery - ‘The problem of the whispering gallery’.

Unfortunately, that paper is dry and confusing and from 1880, so here’s a rundown:

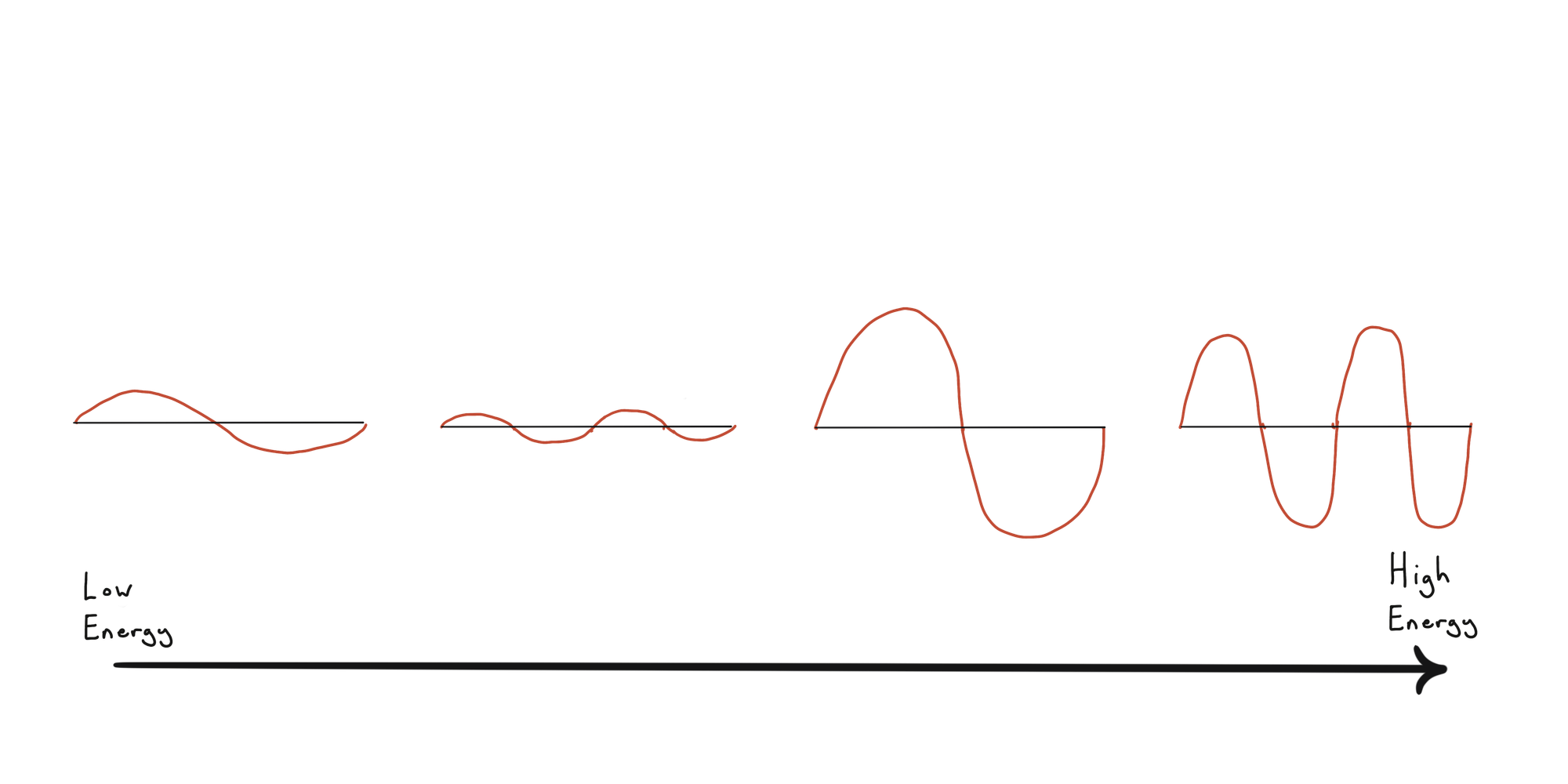

When a sound is made it has a loudness (amplitude) and a pitch (frequency). The energy of a sound wave is dependent on these:

When a sound wave travels straight across a room, it bumps into all the things in the way and its energy is dispersed making it too quiet to hear. The Berkeley’s whispering dome lets the sound take a different route to your ear, bouncing across the dome over the top of everyone in a series of reflections.

But there’s something else going on as well. When a sound wave bounces off a surface, it loses some of its energy to the surface - making it vibrate too. You might expect that if a whispering gallery wave is bouncing many times to cross the room, by the time it reached your ear it would be too quiet to hear, but this is not the case. Instead an effect called resonance allows the wave to retain more of its energy.

You’ll already know resonance intuitively. When a vibrating system (like a sound wave) encounters another object vibrating at just the right frequency, its amplitude (the amount it’s waving) can get way bigger, taking on a lot of the other object’s energy. It’s the same effect that lets you double bounce your friend on a trampoline.

This effect will only happen if the ‘natural frequency’ of the surface roughly matches the average frequency of the sound. For the big, hard, stiff walls of St Paul's, this frequency is high (fast vibration – think of a tight guitar string) and so the effect only works with equally high frequency whispers. In the Berkeley however, the dome isn't backed by anything (as I discovered from the plans) so the natural frequency of the glass dome is much lower (the glass 'wants' to vibrate slower). This is why it can reflect normal speech so well across the room, into your ear.

An attraction

People have been designing buildings to sound a certain way since medieval times, and the field of modern acoustics was evolving rapidly in the 19th century. It seems very likely the architects of the Messrs Cadina Café hoped their dome would attract visitors. Whispering galleries were probably pretty damn cool then. Discovered 40 years ago by the time Messrs Cadina Café was built, it would be kind of analogous to a club now having a 3D printer. I'd go, that sounds sick.

Though it seems to be a general Wetherspoon's policy to buy up old buildings, I wonder whether the ‘whispering gallery’ played a part in the preservation of 15-19 Queens Road. The dome certainly serves the same purpose it always has - I've just spent 1000 words talking about it.

Google reviews for the Berkeley are also filled with references to the stained-glass dome and its peculiar sonic properties. I suppose freaky science-cum-magic doesn't go out of fashion.

That's all well and good, but it does mean that a central pillar of Bristol's nightlife poses patrons the risk of accidentally majorly spilling the tea.

And causing drama - I won't let this one rest @ chemistry opp.

Featured images: Corin Hadley