By Oli May, Second Year MA Liberal Arts with French

From Afro-diasporic sound to sculptural ruin, Spike Island’s latest exhibitions invite us to listen, linger, and rethink how art holds history and meaning.

As a student fascinated by the critical power of visual art and cinema, I jumped at the chance to attend the press preview of Spike Island’s latest exhibitions - partly out of curiosity, partly because it felt like a necessary rite of passage for a Liberal Arts scholar. On Thursday 29 January, I had the pleasure to experience Feedback by Olukemi Lijadu and RAIN/RUIN by Phillip Lai: the former an immersive film installation, the latter a collection of sculptural works. This article traces what these exhibitions imparted to me - intellectually, sensorially, and politically - and reflects on why they are worth your time. More than a review, it is an invitation: to engage not only with these exhibitions, but with Spike Island itself, as a site for contemporary art, critical thought, and aesthetic encounter.

Feedback - Olukemi Lijadu

Nigerian-British artist, filmmaker and DJ Olukemi Lijadu makes a striking institutional debut at Spike Island with Feedback, a film that reclaims the Afro-diasporic origins of electronic and house music. Developed through research across Chicago, Detroit, Lagos and Bristol, the work is firmly rooted in what Paul Gilroy terms the Black Atlantic - a framework Lijadu cites as foundational. Tracing sonic echoes across continents and generations, Feedback dismantles the persistent myth that Black communities were peripheral to electronic music, instead restoring rhythm, drums and repetition as its core. Here, rhythm becomes more than sound: it is a method of remembering, a carrier of history, and a technology of connection and survival.

After an introductory talk, we were ushered into the exhibition: a vast, darkened room that immediately dissolved any sense of conventional spectatorship. We were invited to sit wherever we wished. I chose the floor, leaning against a long, plush beanbag, watching from a low vantage point. It felt deliberate - grounded, communal. The film unfolded across a split screen, images diverging and converging, occasionally stretching across both frames. Paired with surround sound, whose frequencies and tones felt soothing, the effect was profoundly immersive, enveloping the body as much as the eye. The viewing conditions mattered. Sitting among other writers, bodies gathered loosely on the floor, the space itself seemed to enact the film’s logic of togetherness or shared presence.

Three elements, in particular, left a lasting impression. First: the drum. Operating both as a physical instrument and a symbolic language, it emerges as a technology of communication. Lijadu explained that drums historically transmitted messages - especially during enslavement - functioning as a covert language when speech was forbidden. This reframed my experience of the film entirely. Watching Feedback felt transcendental, as though I had entered a different mode of knowing, communicating and being. African house music is presented as communal and sacred, structured around call-and-response, with rhythm acting as a binding force. Repeated loops of bodies dancing - exhilarated, joyful - embody connection through sound and movement.

Equally striking was the work’s intimacy. Lijadu described the project’s genesis as beginning in her living room in Lagos, listening to music with her father. One image shows the pair seated before a futuristic, altar-like sound system, positioning speakers and sound as conduits for diasporic connection. This autobiographical thread deepens through original camcorder footage filmed when Lijadu was sixteen, grounding the work in lived memory.

‘Music here is not entertainment but force - spiritual, somatic, transformative’

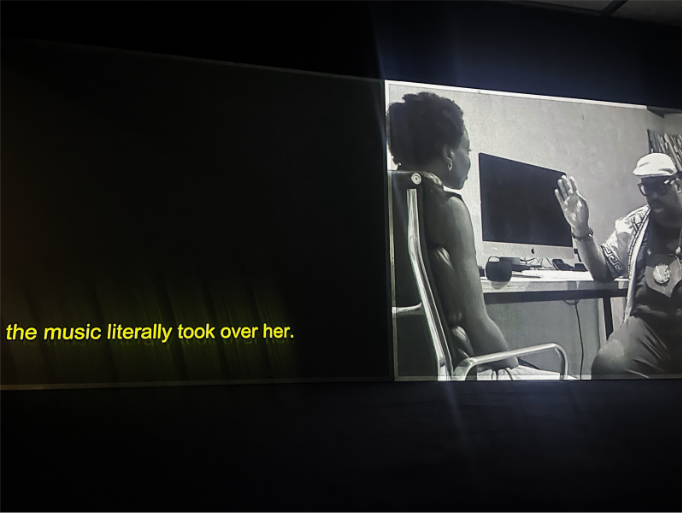

Finally, the film highlights music’s overwhelming power. A DJ recounts a moment in which Josh Milan’s Act 2 + 4 song overtakes a woman’s body on the dancefloor, likened to possession by the ‘Holy Ghost’. Music here is not entertainment but force - spiritual, somatic, transformative.

Formally, Lijadu employs sampling, looping, distortion and echo, likening feedback to waves that travel, mutate and return home. Visually, she resists rigid geometries of control: rectangles give way to circles - a morphology of gathering and continuity. Temporality, too, is non-linear, hovering outside past and future, evoking an Afro-diasporic sense of time. Feedback does not simply represent history; it moves through it, reverberating across bodies, spaces and generations.

The installation incorporates a sound system built by Bristol-based Ramsham Hi-Fi, paying tribute to the city’s sound system culture. Functioning both practically and symbolically, it amplifies histories, voices and vibrations. The exhibition unfolds as a dynamic environment of film and soundscape and will culminate in Lijadu’s live performance at Spike Island on 23 April - an expanded cinematic experience in every sense, and one that embodies the ‘expansiveness’ Lijadu hopes audiences will carry with them.

RAIN / RUIN - Phillip Lai

RAIN / RUIN is Phillip Lai’s most significant institutional exhibition to date, bringing together ten new sculptural commissions that extend his long-standing investigation into materiality, use, and erosion. Born in Kuala Lumpur in 1969 and based in London since childhood, Lai’s practice is defined by an intense attentiveness to how everyday objects are made, handled, and ultimately exhausted. His sculptures do not represent the world so much as recast it, producing parallel versions of reality, stripped of function yet saturated with meaning.

Lai works with ubiquitous objects - trays, bowls, basins, beds, cages - forms associated with containment, sustenance, and care. Yet these objects are rendered unusable. Their familiar ‘grammar’ is quietly dismantled through subtle distortions, misalignments, and material substitutions. What remains is a state of suspension: objects caught between use and ruin, presence and absence.

Lai’s sculptures are evidently the result of slow, meticulous processes, often involving repeated casting and remaking. Materials include wax, stainless steel, concrete, resin, pewter, burnt wheat, glass and ceramic. This labour-intensive approach contrasts sharply with the apparent simplicity of the final forms. The sculptures feel anonymous and transient - located in a temporal and spatial ‘elsewhere’ where utility has drained away, but beauty lingers.

A recurring tension emerges between:

- sustenance and depletion

- containment and exposure

- the sacred and the utilitarian

- surplus and destruction

This ambivalence is central to Lai’s practice.

Most sculptures are low-lying and horizontally oriented, amplifying a sense of exposure within the vast white gallery. Objects are often placed on tarpaulins or isolated within open space, reinforcing their displacement from everyday contexts.

Dominating the central gallery is a large, elevated metal cage, suspended high above the floor. Embedded within it is a speaker emitting a looping soundscape: somewhere between rainfall and demolition. This sonic layer seems to give the exhibition its title, RAIN / RUIN, collapsing environmental cycles and industrial decay into a single rhythm. The cage governs the room not through spectacle but through atmosphere, producing a state of peripheral alertness - felt rather than consciously registered.

‘Once function falls away, beauty is finally allowed to surface’

Lai’s work does not offer narrative or symbolism in any direct sense. Instead, it operates through material relations - how objects absorb time, labour, erosion, and history. By rendering objects unusable, Lai does not strip them of meaning; he exposes their latent beauty, their vulnerability, and their dependence on systems we rarely question. The work recalls Kant’s idea of purposiveness without purpose: once function falls away, beauty is finally allowed to surface.

Though deeply interior and introspective, the work engages outwardly - with infrastructure, urban space, and ecological precarity - positioning sculpture as an interzone: a site of passage rather than resolution. RAIN / RUIN is not about objects as things, but about what remains when use collapses. It asks us to sit with ambivalence, to notice erosion, and to read meaning in the quiet after function ends.

Spike Island

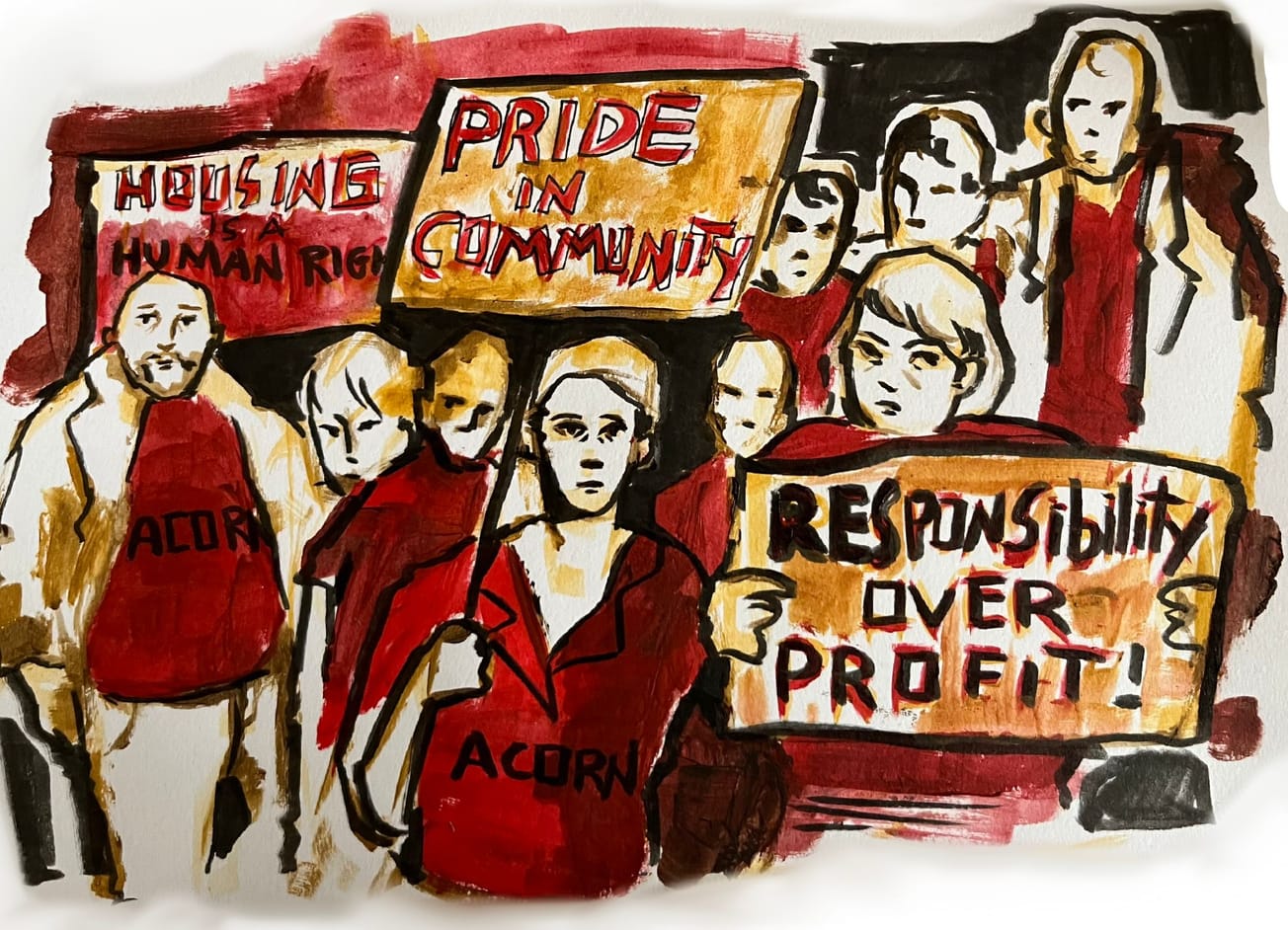

Beyond the exhibitions themselves, Spike Island stood out to me as an institution. Housed in a vast former industrial building on Bristol’s harbourside, it is far more than a gallery space: Spike Island supports over 70 subsidised studios and is home to hundreds of artists and creative businesses, fostering a vibrant, close-knit creative community. The atmosphere feels welcoming rather than imposing, shaped by an affable curatorial team and a genuine commitment to access and inclusivity.

This inclusive ethos extends beyond the galleries. Emmeline, Spike Island’s on-site café bar, serves delicious, reasonably priced food, with thoughtful options for vegan, gluten-free and other dietary requirements. Crucially, Spike Island’s ambitious exhibition programme is largely free to the public, opening contemporary art to audiences from all backgrounds. As the organisation marks 50 years since its inception, 2026 is set to be a celebratory milestone. Spike Island is, without question, well worth a visit.

Feedback and RAIN/RUIN run from 31 January to 10 May 2026.

Featured image: Oli May

Will you visit these exhibitions at Spike Island?