By Charlotte Kerby, Deputy Features Editor

Football is a cherished part of British culture, whether you know the offside rule or not. Get me and the girls a cheeky pint down the pub in front of a EUROs game and my weekend plans are set. But how does the football industry fail its spectators and players in terms of its approach to inclusion?

If I’m being really honest, men's football had always been an action-packed excuse to socialise at the pub for me. Nothing beats the drunken excitement of a penalty shoot-out, or an insane last-minute shot on target, but I’m by no means a lifelong fan. The rise of the women’s game, however, has brought out something a bit different in me. Ever since the 2022 EUROs I have been a stickler for the underdog and I know I’m not alone. The Lionesses make football feel progressive, like the future of football doesn’t lie in quite so murky waters. So how exactly does the men's game compare? And what is its future?

For many, football fans have a terrible reputation, awash with hooliganism, racism and bigotry. There is the too-often prolific use of homophobic language, racist and nationalist violence from the men's game spectators, and a dearth of LGBTQ+ diversity on the pitch.

It’s not exactly a glowing review, is it? Of course, I’m not claiming the women’s game is immune to all of this, and I'm not claiming the men's game always involves this. But if we really considered the moral standings of the professional football industry in England, would we be so eager to watch a game?

Within the men’s Premier League there have been no openly gay male players out during their professional career. Yet, within the 2025 EUROs tournament alone the England Lionesses featured plenty. Why?

Prevalent baller Justin Fashanu, once an England Under 21s player, was the most professionally successful and publicly gay player the English men’s game had ever seen. His career in England, however, was cut short when his sexuality became known following a coerced media outing in 1991. Fashanu began to coach overseas in the USA, attempting to escape the homophobic and racist dialogue imbedded within the British game.

Yet, following an unfounded sexual assault accusation of a 17 year old, unrelenting homophobic and racist abuse, and horrific coverage in the press, Fashanu spiralled and committed suicide in 1998. Fashanu said before his death that he knew of at least 12 other gay or bisexual players in the Premier League. Yet none spoke out during their career, before or after his death.

The men's football industry in England was not a welcoming place to be. Justin’s own brother John said on Justin's sexuality that ‘I wouldn’t like to change or be in the vicinity of him.’ He also declared that he begged his brother not to publicly come out, offering to pay Justin the same as what The Sun was offering so that he did not have to publish the story.

The discriminatory attitudes to Justin's sexuality from his own family only perpetuated silence from gay professional players. No English male player in the top division has come out during his career since.

Whilst this discriminatory abuse dates from the 90s, homophobic chanting is still very much prevalent today, with Ben Chilwell being called a ‘Chelsea rent boy’ by Millwall fans at a recent game. Whilst the FA intervened and fined the club £15,000, it is unclear what tangible action the club have taken to tackle this behaviour. And, if we’re honest with ourselves, £15,000 for a Championship level club does seem to be more performative than genuinely punitive.

So, what makes the use of homophobic slurs in the football grounds ok for so many people? Why is there an unspoken rule that it's ok in one setting and not in the other - and why are Premier League clubs allowing this behaviour to continue?

The answer is complex - but what I can say for sure is that football is an environment of power and pride. Homosexuality, in the men's game, is viewed as weakness, and homophobic chants are used as mechanisms to shame the other side.

Happily, there is a marked contrast in the women’s game. Spectators of the game are often shrouded in rainbow flags, owning a culture of unwavering support for their heroes and welcoming the team members' diverse sexualities.

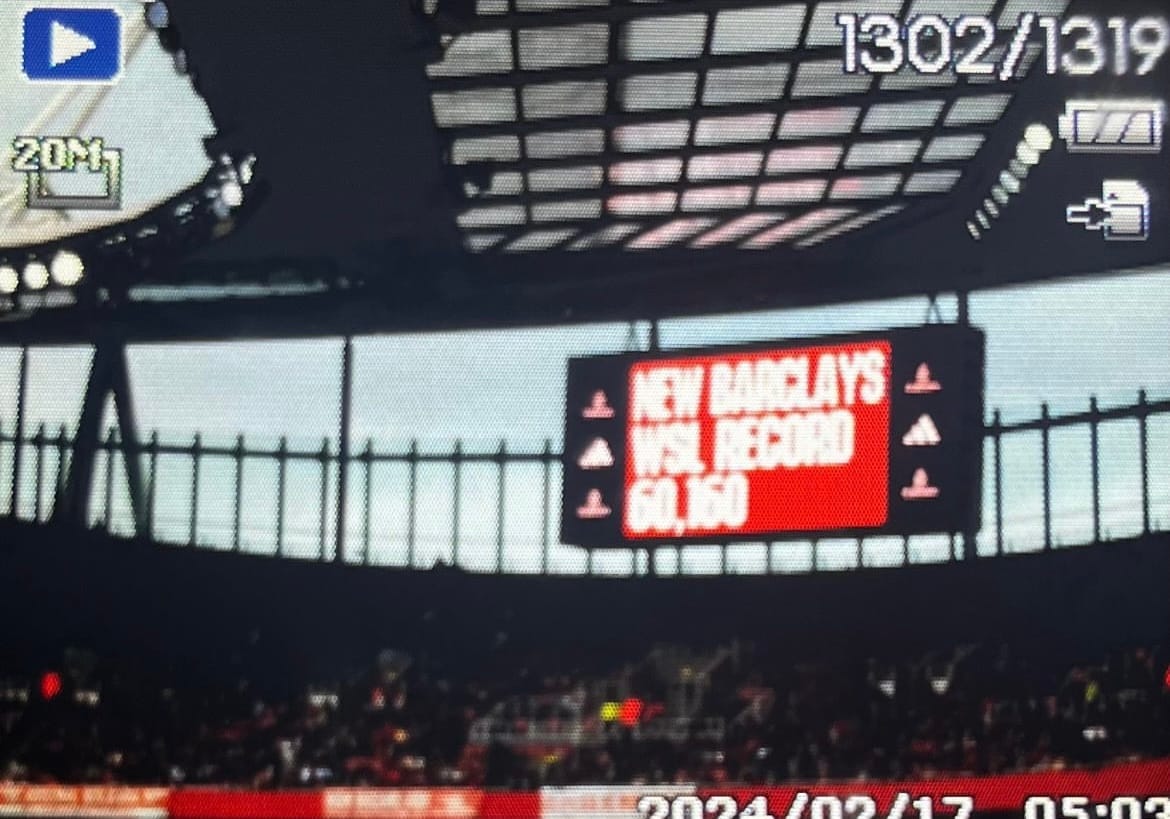

One contributor to this differing football culture could be the demographic in attendance at the women’s game. Research published by the Football Supporters’ Association highlights that attendance of women’s games in 2024 was split evenly across age groups, and women outnumbered men by almost two to one. Perhaps the children in the stands discourage such insulting language from being used, or perhaps the diluted male presence lessens the herd behaviour driven by toxic masculinity. Another reason could be that the professional industry of the women’s game is a lot younger than the men’s.

It is not news to anyone that Britain has a heavy emphasis on tradition, with football club fandom passed down through families and chants carried through the ages. A newer fandom might mean a more progressive fandom. And another route to pursue is of course the difference in gender of the players - is success and sex with women conflated in quite the same way as the men's game? Regardless, the marked difference in the culture of men’s and women’s games has had consequences. Bristol City is trialling alcohol in the stands at their Women’s Super League games due to the lack of antisocial behaviour, whilst continuing to maintain the ban at men’s games in accordance with the law.

Whilst I'm (just about) aware alcohol is not the most important feature of a football game, the presence of pints in the stands implies the club has a greater level of trust in the women's fans than the men's in the stands, a judgement that begs the questions of 'could the women’s game be the football fandom’s saving grace?'.

Managers and key players in the game are also paving the way for greater inclusivity. The 2022 Men's World Cup was held in Qatar, a country with harsh laws condemning homosexuality. As such, One Love Rainbow armbands were forbidden from being present in gameplay, with punishments of yellow cards and game bans. Leah Williamson, the captain of the England Women's national team the Lionesses, spoke on this decision at her Oxford Union address:

'I’m telling you now if I was at the Men’s World Cup when they were threatening to card players and ban players, I would have served the ban. I wouldn’t have played a game because there’s no way I wouldn’t have worn that armband onto the pitch in that moment.'

It speaks volumes that this attitude, of sacrificing performance to campaign for the rights of the LGBTQ+ community, was ultimately not adopted by the England men's team when push came to shove in Qatar.

LGBTQ+ activism in football isn’t just a feature of the English team. Across the Atlantic, Megan Rapinoe, an American national soccer hero, has repeatedly spoken about LGBTQ+ rights on and off the pitch, making her support for trans inclusion in sports public in 2022.

Such an inclusive stance on gender inclusion, however, is not taken by the FA. Following the UK Supreme Court ruling on April 16 deeming the term ‘women’ a label solely for those biologically assigned female at birth, the Football Association banned any transgender women from playing football in the women’s game across all divisions in England.

Stonewall found in 2018 that over 50 per cent of LGBTQ+ people experienced depression, and The Office for National Statistics found that in Autumn 2022, 16 per cent of adults of any sexuality or gender identity experienced depression, highlighting that the LGBTQ+ community experience an elevated amount of depression compared to the straight community.

Given that Sport England have identified the varying positive impacts sport has on mental health, it seems backwards that transgender people, a group who statistically experience more mental health problems than their cis, straight counterparts, have been excluded from the benefits of sport in grassroots teams by football's governing body.

The football industry seems to be far more exclusionary than I’d like it to be. But some approaches to discrimination in the game give me optimism. Pay for the women’s game increases every tournament, as does spectatorship. And with integration of the men and the women’s division growing, perhaps the women's example of inclusivity of all sexualities can be followed. Change is definitely on the horizon for the game. But with key governing organisations in football failing to secure inclusion and safety for all players, it’s hard to see whether a progressive future, pursued by key playmakers or not is actually coming.