By Sagal Khalif, Second Year, Law

“I love you despite your olive skin”

The casual concern in my aunt’s voice telling me to get up from under the sun, lest I become too dark, not only broke the midday quiet but the rest of my fifteenth birthday. Her words, spoken with a casual concern only an older relative could have, caught me off guard. It was a simple comment, but it struck a deep chord. Is whiter better? The thought lingered in my mind, unsettling in its simplicity. The vast majority of my family are lighter skinned than I was, but I had never thought much about it until that moment. Now, as the sun began to dip, the question felt pressing, demanding an answer. Later that evening, I watched my young cousins, with innocent concentration, wrap their hands and feet in plastic bags and socks, trying to emulate the whitening techniques they’d seen the women in our community use. Again, I was left wondering: Was this fixation with lightness just a game, or had it become so ingrained in our lives that it was something we, too, would pass down without question?

The desire for lighter skin is not just an individual choice but an ancient, global fixation with unsettling roots. Skin bleaching may feel like a modern crisis, but history reveals it as an inheritance, one that threads through empires, classes, and cultures. Practices of lightening skin were already prevalent among ancient Greeks, Egyptians, and Romans, where a pale complexion was seen as feminine, pure, and desirable. Wealthy Roman women covered themselves in a ceruse mask made of white lead and vinegar—a ritual echoed centuries later in ancient China and Japan, where women used white lead and rice powder to craft a luminous, mask-like effect. In East Asia, the proverb “A white complexion is powerful enough to hide several faults” captures the relentless pressure to appear lighter, a tradition that, sadly, holds a bitter relevance today.

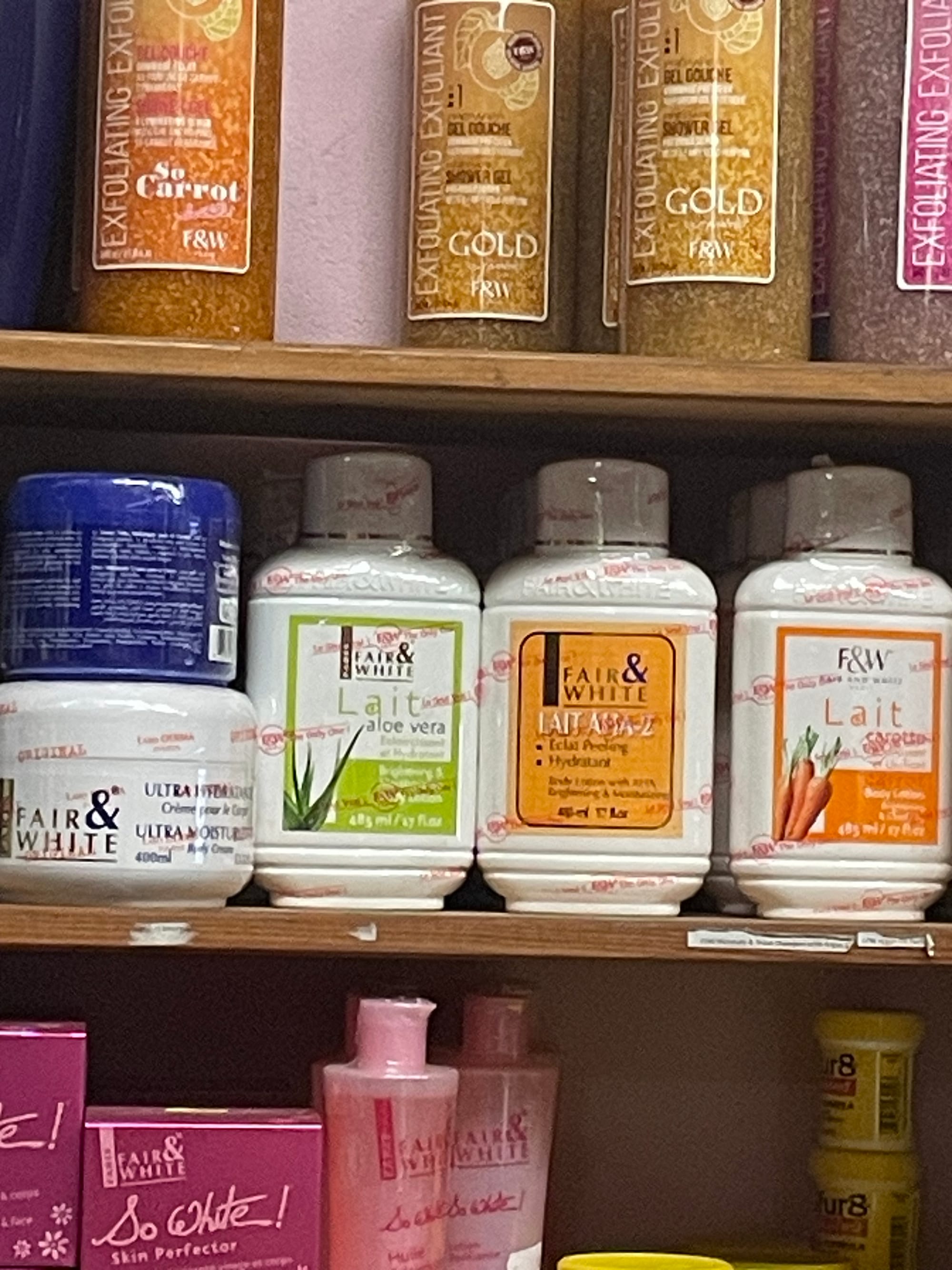

In many regions of the Global South, skin bleaching has evolved into an enduring, disquieting obsession. Recent data from the World Health Organization reveals the scale: Nigeria leads with 77% of women using skin-lightening products, while in Congo-Brazzaville, 66% follow suit. Ghana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa report similar trends. These numbers tell a painful story of internalised ideals, where millions undertake daily bleaching routines that sometimes lead to physical harm, all in the name of a beauty standard that venerates lightness over natural diversity.

What perpetuates this trend? A potent mix of historical remnants, economic motivations, and social expectations. In Africa and the Middle East, where European colonialism left a brutal legacy, the hierarchy of skin tone lingers, casting shadows across modern societies. Those with lighter skin were once treated as more civilised, more deserving of power—a notion upheld through laws, labour divisions, and societal privileges. Salwa, a well-educated woman from Cairo, recalls her boyfriend’s words: “I love you despite your olive skin.” For her, lightening creams are not simply a cosmetic luxury but a means of fitting into a world that still quietly insists that to be fair is to be favoured.

The motivations for bleaching go beyond appearance. In many contexts, it serves as a form of economic aspiration. In cities with high unemployment and poverty, fairer skin is seen as an asset, particularly for women, who find that a lighter complexion can improve their chances in work and marriage. In poorer areas like Cairo’s Bulaq al-Dakrur district, lightening creams are available even to teenagers, who find themselves pressured to emulate a paler standard of beauty, be it through branded products or risky, unlabelled bottles from neighbourhood shops. This isn’t simply a matter of vanity; for many, lightening skin feels like a way to survive in a world structured by old biases.

The paradox is undeniable: in countries rich with heritage, people strive to erase part of themselves to become “better,” to fit a narrative they never chose. This dynamic is especially heart-breaking when we consider the mental toll, the sense of shame and inadequacy ingrained in each application of cream. It creates a painful internal dialogue, a constant question of worth that gnaws at self-esteem and cultural pride. Among the younger generations, the effects are profound. In Ghana, nearly half of those surveyed in Kumasi had engaged in bleaching practices, and the highest prevalence of bleaching is found in people under 30, who inherit the insecurities of a past they may only vaguely understand.

In this obsession with lighter skin, we have forgotten a crucial truth: beauty is diverse, a spectrum as vast as our histories and stories. The differing shades of brown and black are not only beautiful but are the source of countless amounts of folk songs. Yet, as communities, we continue to reinforce the opposite message. This is the silent inheritance we pass on, a collective unwillingness to shed the ideals handed down by foreign empires, ideas that equate whiteness with purity, with worth, with humanity. The cultural erasure this obsession entails is as distressing as the physical harm it inflicts. It is, in effect, a form of quiet violence against our heritage.

In challenging this engrained mindset, the responsibility falls not just on individuals but on communities, governments, and industries. It is a call to reclaim beauty standards on our own terms, rejecting the colonial legacies embedded in our perceptions. While campaigns have made strides to celebrate darker skin and encourage self-acceptance, they are still a small countercurrent against a larger tide. The movement to reclaim beauty must be relentless, woven into the fabric of education, media, and daily life to slowly dismantle centuries of harm.

In the end, the question of whether lighter skin is truly better lingers, not just as a personal reflection, but as a broader cultural narrative that shapes how beauty is defined in many parts of the world. Skin bleaching, with its deep roots in colonial history and reinforced by modern beauty standards, continues to perpetuate the belief that fairness is synonymous with worth. As I watched my cousins mimic the practices of those around them, it became clear that this cycle is far more than a superficial concern—it is a deeply embedded part of how we see ourselves and each other. What’s more unsettling is that this obsession with lightness is passed down, almost unconsciously, from one generation to the next. Perhaps the real challenge lies not in lightening our skin, but in questioning the standards that make us believe we must.