By Maya Tailor, Features subeditor

The smiles of surprise, the raised eyebrows; I remember the impressed, albeit bewildered, look on my relative’s faces when I told them I wanted to study English at university. As an Indian person, I had always felt the weight of the underlying cultural expectation to enter a high earning field of study (bonus points if it was a STEM-related field!). For them, subconsciously or consciously, a degree in the humanities was a waste of time and money. The career pathway was dreadfully unclear and the content, to them, was too ‘white’ and boring. Alongside this, I didn’t know of any other South Asians who had pursued the humanities. All of these factors made me aware that English would not be the most ethnically diverse course. At the time, I didn’t fully understand the gravity of this. What I definitely didn’t anticipate was how this lack of diversity would manifest itself within the structure and the content of the course.

Having grown up in north London, every classroom I had inhabited from primary school up until sixth form was incredibly diverse. I didn’t know any different. To go from this to lectures theatres and seminar rooms that lacked the diversity I was accustomed to was a strange experience. I thought I knew what to expect walking into these spaces, but they bewildered me more than I ever thought they would. It went beyond feeling nervous. I felt like I didn’t belong in this particular environment and that it wasn’t made for me. It was unfamiliar and unnerving in a multitude of ways that I didn’t know how to process.

Seminar rooms especially presented me with a unique set of challenges that only solidified the isolation I felt. English is a large enough course that in a majority of my lectures, I could spot the handful of brown people sitting alongside me. However, in some seminars I became conscious of the fact that I was the only person of colour in the room. I’m not entirely sure if my white counterparts were aware of this dynamic, or if it was something that even crossed their mind. Why would it? I was just another face in the room, because this imbalance is non-existent when you’re not the one being weighed down by it.

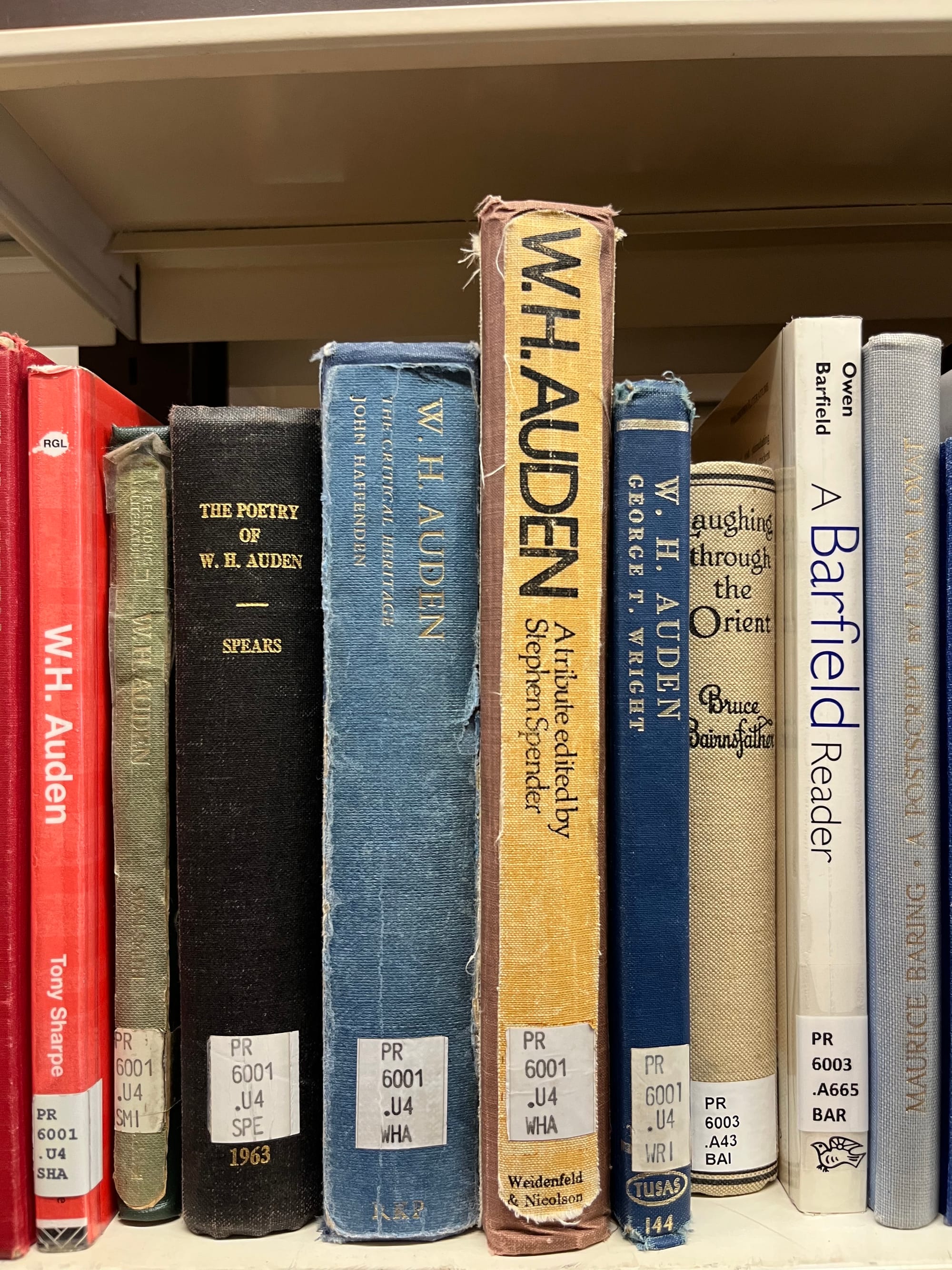

This weight became pressing as my seminars progressed and we delved into yet more work by prominent white authors of the literary canon. In one of my modules last year, deceptively called ‘Literature 1900-present’, most of the texts prescribed for this module were written by white people, mostly men. This isn’t to say that the English course at Bristol doesn’t have its moments of inclusivity. I’ve read and written about some great writers from across the Global South. But this is precisely the issue. Their works are reduced to moments. A passing comment in a lecture loosely linked to focus writer or text for that week.

‘If we acknowledge that there is a systemic lack of diversity within the content, we also need to accept that the content is chosen by an overwhelmingly white teaching panel, for an overwhelmingly white cohort of students’

Writers of colour, especially South Asian writers, are hardly seen in the larger, compulsory breadth modules. Their works are reduced to a singular optional module. Don’t get me wrong, it is great that this detailed study of the South Asian diaspora is on offer, but by reducing it to one module, it suggests that works like this – and what they represent – are not worthy of being included in the wider field of study. Brown voices need to be studied in both forms in order for a course to be considered inclusive.

The lack of diversity within the English course content is also a reflection of the demographic of the course itself. And by the demographic, I mean both students and tutors. The content is not set in stone, and is constantly being adapted year upon year. The texts that are on offer are chosen by tutors because they either resonate with them or are part of a wider topic in which they specialise. If we acknowledge that there is a systemic lack of diversity within the content, we also need to accept that the content is chosen by an overwhelmingly white teaching panel, for an overwhelmingly white cohort of students. By catering it to such a small worldview, it restricts the opportunities to learn about literature outside of the traditional western canon, and the complexities and histories that come along with it.

So what does this all mean? The fact is that there aren't a huge number of South Asians opting for humanities subjects. According to various studies, it was found that South Asians were far more likely to study Science, Medicine and Engineering compared to their white counterparts, stemming largely from their parent’s desire for social mobility. The issue isn’t the number of South Asians in higher education – it is that they are choosing pathways that will guarantee mobility and higher earning potential. When we also consider that the number of people applying for arts and humanities courses generally is decreasing, it isn’t surprising to see a lack of brown representation in this field of study.

Although this is only one interpretation, it doesn’t change the fact that brown people still enter the arts and humanities. We do exist and we deserve to have our voices and experiences represented in our education. We are a part of lectures and seminars, which justifies the importance of adapting the teaching from a Eurocentric perspective to one that goes beyond this lens. The lack of South Asian voices within the content has only intensified the lack of South Asian people within the demographic of students. It has created this wider culture from which many may feel disconnected, and within which they may feel unwelcome. I know I have experienced the layers of unfamiliarity that come with navigating such a complicated space. And whilst I can appreciate the small changes being done to the content, I know more can be done to champion South Asian voices and inclusivity.

Featured image: Epigram / Leah Hoyle

Do you feel that marginalised perspectives are represented within your course?