By Benjamin Seekings-Jenkinson, Second Year, Anthropology

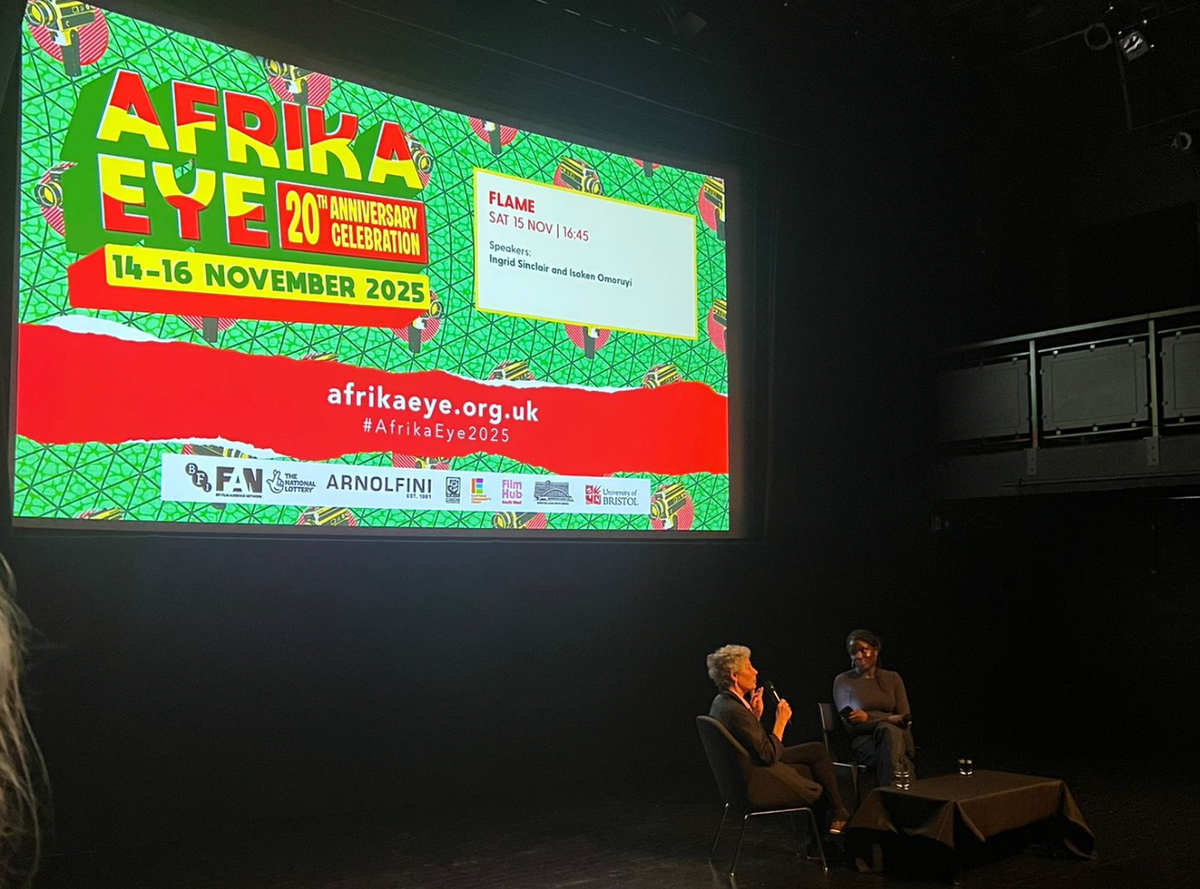

I was fortunate to attend the Afrika Eye festival on Sunday 16th of November this year, celebrating their 20th anniversary in a weekend rich with creativity.

The film events that I attended, The Anchorage of time (2024) and Come Back Africa (1959), took place at the Arnolfini Centre, Bristol’s International Centre for Contemporary Arts, located in the heart of the city. Due to my own South African heritage and having not attended the festival before, I was intrigued as to what the festival would entail, what experience I would have, and what topics the carefully selected African films would present to an audience in the UK.

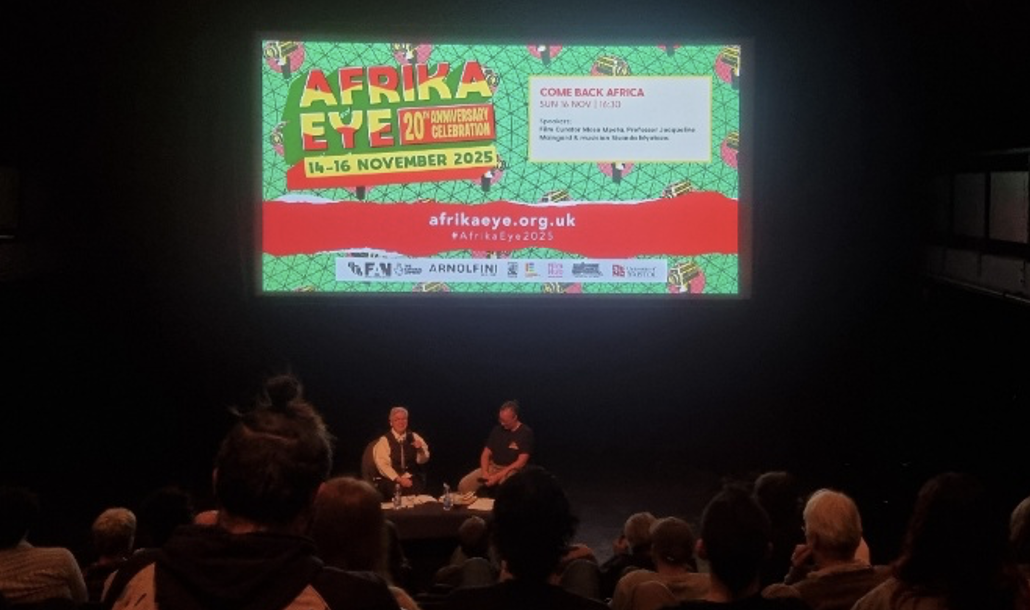

Arriving at the Arnolfini, I was immediately met with a warm and friendly atmosphere and a community feel as everyone waiting to view the film congregated in the main hall of the building. Each film felt very well organised and was followed by a Q&A session, which helped to unpack themes presented and explore the emotions generated by them.

Come Back Africa featured a beautiful performance by South African musician, Sisanda Myataza. After the film, the audience were welcomed back into the main hall for complimentary drinks and snacks, creating a space for the audience to discuss and share their ideas about the film they had just seen.

The first film that I attended, The Anchorage of Time (2024), was a murder mystery directed by Sol de Carvahlo, based on the book A varanda do frangipani by Mia Couto. Set in a retired colonial fortress on an island off Mozambique, a police detective arrives to solve the murder of the director of the island. As the film goes on, he collects contradicting and confusing accounts of the crime, which hide the truth of what really happened.

A fellow audience member turned to me after the showing had finished, telling me how she ‘didn’t know what would happen next’, and how her attention had been kept for the entire film. The cinematography was beautiful, the acting of the very small cast was marvellous, and the use of straight to camera monologues presented an intriguing way of giving the backstory of each character.

The film also included important issues present in modern day Mozambique, the illegal albino organ trade and the pangolin scale trade. I personally felt these themes were not explored nearly as much as they should have been, and only cropped up a couple times, feeling more like a late add-on rather than a key part of the plot.

However, some credit can be given for including these themes at all, and it contributes to bringing awareness to atrocities that the audience may not know about, including with myself and the albino organ trade which I felt compelled to educate myself about after the film had finished. The Q&A between Professor David Brookshaw (the translator of the original book from Portuguese to English) and Dr Edson Burton helped to explore the themes further and break the film down.

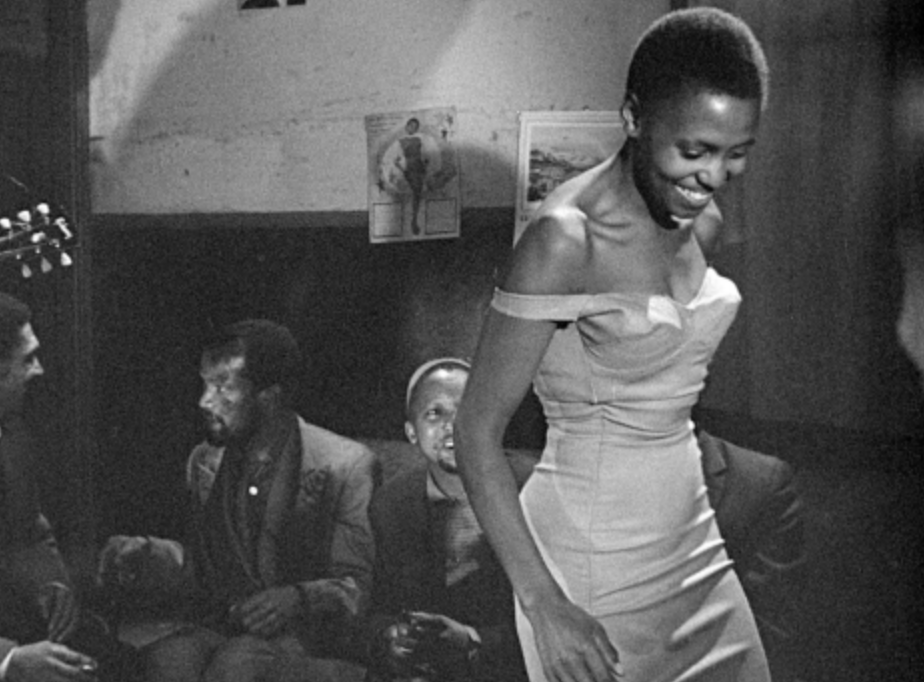

The 1959 film Come Back Africa followed, directed and secretly filmed using guerrilla film tactics in South Africa’s apartheid by Lionel Rogosin. It features non-professional actors and real people living under the apartheid regime in Sophiatown, a (now destroyed) racially segregated ‘township’ in Johannesburg. The film follows the story of the character of Zachariah, a black man who moves away from his family in rural South Africa to pursue work in Johannesburg, with which he is mostly unsuccessful due to heavy, racially segregating restrictions from the apartheid government on work and housing.

The film is heart-wrenching, portraying the everyday struggles of a black person living under the oppressive South African apartheid state. The moments of conversation throughout provided insight into life under institutionalised oppression, from the instances of small banter to scenes of intellectual debate between individuals such as the writer Can Themba at the local ‘Shebeen’ (illegal bar).

The film even featured an appearance from the then-unknown Miriam Makeba, later becoming the famous black South African singer, actress, and civil rights campaigner she is known as today. After the film, a Q&A followed between University of Bristol Professor Jacqueline Mainguard and film curator Mosa Mpeta. Along with the exceptionally informative introduction by Professor Mainguard herself before the film, the Q&A provided all the necessary context to the film as well as unpacking the visceral feelings brought up.

Come Back Africa is just as relevant today as it was when it was first released. Not only does it shed light and educate those watching on the history of oppression of black people in South Africa, which many people in the UK may not be familiar with, but it also reminds us to remember and campaign for those who are being oppressed and persecuted in the rest of the world.

Attending the Afrika Eye Film festival was a wonderful and culturally educational experience. Through the films shown, it fostered engagement with its audience and created a community space for education and cultural celebration.

Important discussions around heavy topics of history and the modern world show how much value there is to bringing African made films to a multicultural city like Bristol. I urge those reading to keep an eye out for the festival next year.

Featured Image: Epigram / Benjamin Seekings-Jenkinson

Epigram is hugely grateful to Annie Menter and Pam Beddard for organising the event and offering exclusive access to the events across the weekend.

This event was featured in the November edition of Epitome: Epigram's monthly go-to guide of unmissable events across Bristol. Sign up here to receive our curated newsletter in your inbox!