By Lucy Ilett, First Year, Politics and Philosophy

For most people, Christmas is a time for celebration and togetherness in the depths of winter. But for others, it can also be a difficult period which brings experiences of grief, loneliness and financial strain back to the surface.

Christmas isn’t always as ‘merry’ as it may seem. My mum and sister died a year apart—let’s start with that. One year I loved Christmas, the next year I liked it, but by the year after too much had changed, and I struggled to find joy in the holiday season. The expectation of celebrating together is a lovely thought, but also disheartening for some, and a little naïve.

The year after my sister died, being in my house during Christmas was like living with people who each spoke a different language. We struggled to communicate, and unlike the rest of my family, I struggled to pretend it was a joyous time. We were six people around a turkey, and a few years later we were four—overwhelmed by loss, surrounded by lights and tinsel, angels and stars.

So, I don’t like Christmas. A few years ago, admittedly before I’d healed a little, I found being told—not wished, but told—‘Merry Christmas’ offensive. I love the lights and the colours, the warmth in a cold space, and I resent the idea that I’m a Grinch or a Scrooge, when really I’m just a griever.

At my worst times, I wished people who knew the story of the past few years had reached out, but I was juggling that selfish and completely understandable grief, with the knowledge that others enjoy Christmas, and don’t want to think about what was—as I saw it—the sob story that was my family.

Christmas is also a consumer-driven event, something which I always massively disliked anyway. As with the ‘rainbow capitalism’ of companies using the pride flag during June, few corporations use the extra revenue to help where they can—though Lidl, B&M Bargains, and The Entertainer are some of those companies that have teamed up with various charities, or founded their own, to provide a joyous Christmas for those in need.

Decorating a family home as if it’s Santa’s Grotto is a lot of children’s dream—until one house has a ten-foot inflatable Santa in the garden, and another just puts last year’s cut-out snowflakes back up on the door. When its time for the January comparing-of-presents in the classroom, kids start to understand—unfairly, and all too soon—that a hierarchy exists, and those conversations may become a memory which a less fortunate child will carry with them forever.

The average household spends around £1,150 on Christmas, according to Credit Union UK. It’s no secret that the ongoing cost-of-living crisis means more families struggle through the Christmas period, trying to afford gifts for their children, a full meal, and the decorations to go with it—those pleasantries which for other people make Christmas, Christmas.

Lots of foodbanks run ‘Christmas Dinner campaigns’, where you can buy a meal for someone in poverty for just £13. Christmas is an expensive time for everyone, but if you can live without that one extra treat, or pick a night in with friends rather than a dinner out, that money could go to making the season a little easier for someone in need—for instance, through donating to the Bristol-based charity inHope’s ‘Big Give’ challenge. The Salvation Army runs a present appeal which distributed 76,000 gifts to children of all ages last Christmas, while other campaigns include Cash for Kids’ ‘Mission Christmas’, Lidl’s toy bank, and Action for Children’s ‘Secret Santa’ appeal[ej1] . It’s also worth finding out what your local church does to aid struggling communities during Christmas, religious or not.

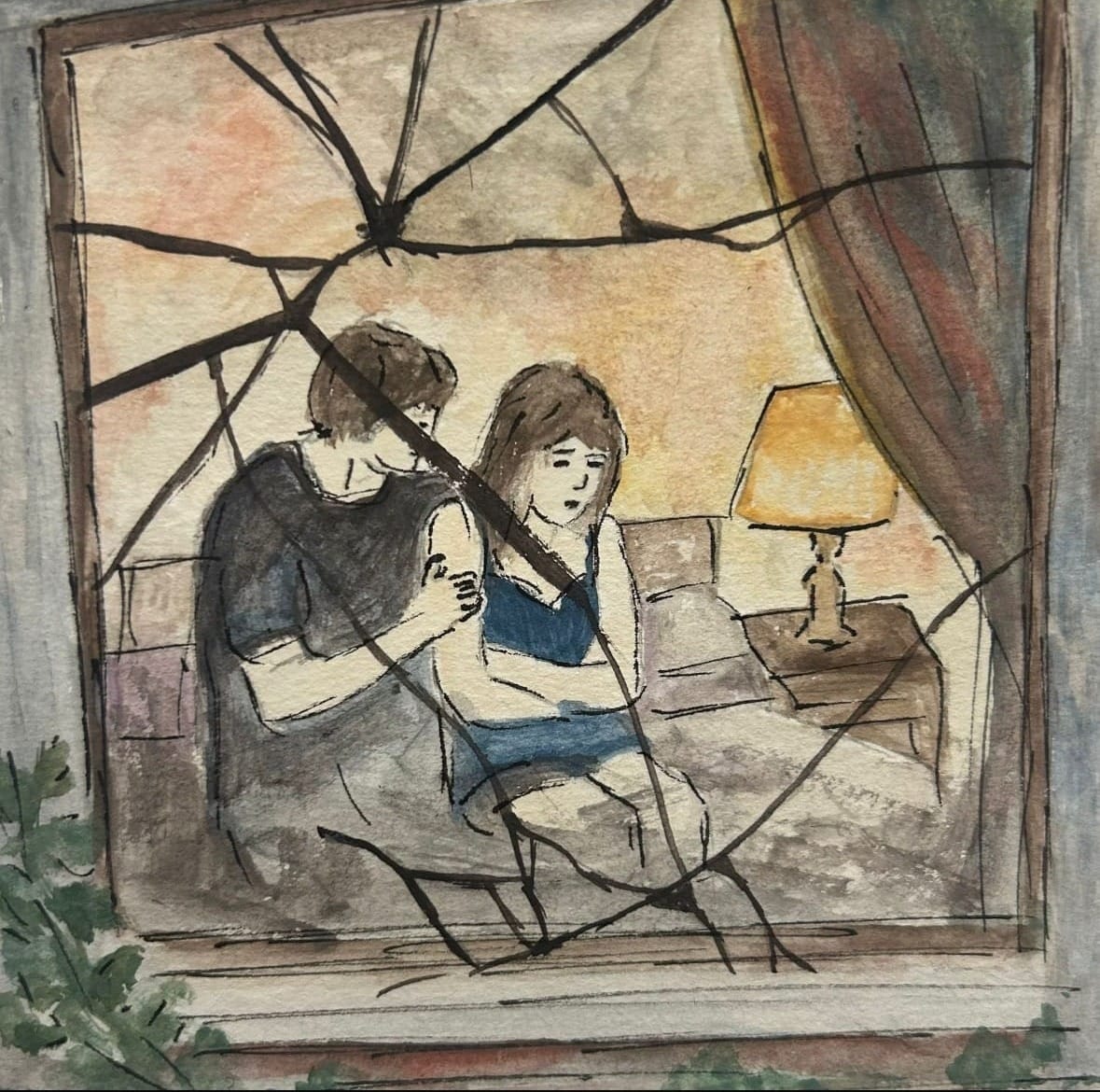

Grief and financial pressure aren’t the only factors which might contribute to a depressing December, either. DVACT says that Christmas 2020 saw the number of domestic violence incidents nearly doubling from 2019, from 200,000 to 369,000—and since 2020, numbers have remained high, while one in six believed they were more likely to suffer emotional or physical abuse from their partner over the Christmas period. Christmas, for some, isn’t just sad—it’s a reason for fear. Act, if you know someone struggling, and understand the signs: sources like the National Domestic Abuse Helpline and Women’s Aid are good for learning to recognize the signs.

At a time of celebration and family, social isolation can—and does—increase. If I took anything from my difficult Christmases, it’s that even in the darkest times, I wasn’t alone. According to Mental Health UK, 74 per cent of people surveyed experienced loneliness and isolation during the festive period. For a university student, that’s just under three quarters of your lecture theatre—almost three out of four people you walk on the street. So to the 74 per cent percent, who might not be counting down the days on their advent calendar come December, you’re not alone.

Featured image: Ellen Jones

Have you been affected by loneliness or grief during the Christmas period?