By Fergal Maguire, Features Columist

‘These countries were using the climate as part of their political argument’.

Antarctic traveller, world expert in Polar history, member of the Iona community in Scotland, epicurean explorer and, of course, lecturer of History here at Bristol University, Dr Adrian Howkins was on the top of my list of people to interview. I wanted to find out about the man behind these endeavours, behind this hugely varied and cultivated life, behind the supposedly unequivocal yet evidently ambiguous title of ‘Lecturer of History’.

Howkins and I sit facing each other in his office, a round table and two mugs of coffee separating us. The room is enveloped in books in a comforting way, and alongside his desk hangs a proud (and colossal) map of Antarctica.

‘Why do you love history, Dr Howkins?’ I ask.

He chuckles - partly at the lack of pleasantry, partly at the thought of his raison d’être. For him, History is about understanding the world we inhabit. ‘I’m fascinated by History’s connection to the present and using it to make sense of the world we live in’.

I was eager to begin with some of the bigger questions in attempt to put his work into some sort of context; to appreciate why he does what he does. ‘Everything that happens in the world today has a back-story to it,’ he says. ‘Environmental problems, political upheavals, economic ventures. I want to understand how things came to be the way that they are.’

As I take a sip of my steaming coffee, Howkins mentions how his work in Antarctica has significant contemporary relevance; the undeniably important geo-politics of the environment.

Why do so many countries want a piece of this frozen wasteland?

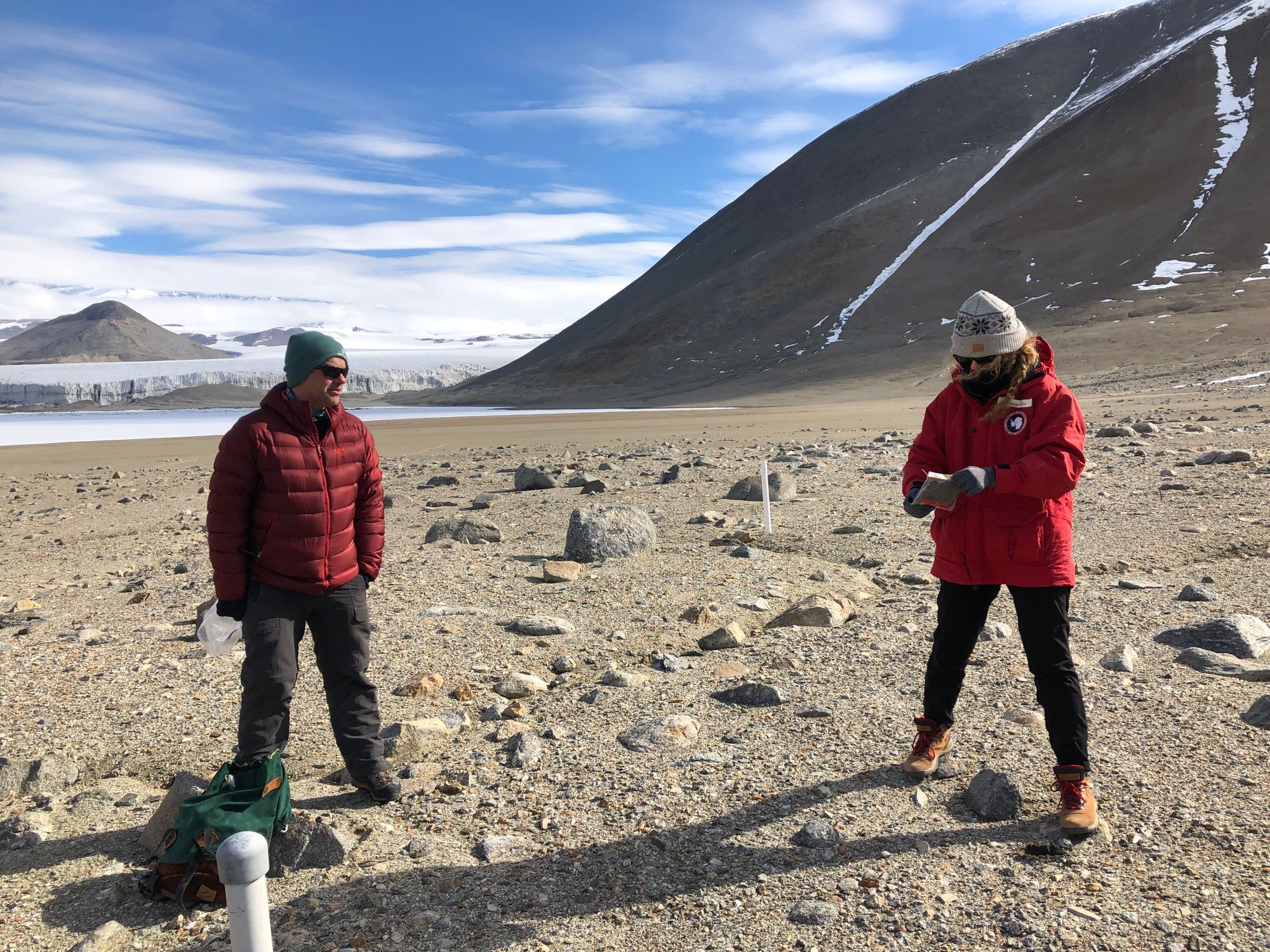

The slightly weathered, hugely warm man sat opposite me has just returned from a four week research trip in Antarctica. His eighth trip out there to date. ‘My interest in Antarctica started when I was in Texas and began solely as a political history; the various claims of ownership between Britain, Argentina and Chile.

Very quickly I realised that this political dispute had very strong environmental dimensions. These countries were using the climate as part of their political argument’. As we set sail deeper into discussion, I noticed we were now both leaning forwards; as if the conversation had taken hold.

Dr Howkins’ book ‘An Environmental History of the Antarctica Peninsula’ is one of his many highly respected pieces of research. Published in 2018, the book explores the way in which countries and imperial powers have passively fought – and continue to fight - over Antarctica in a sort of pseudo cold-war.

Indeed Howkins outlines how Imperial powers, especially Britain, used exploration and the production of useful scientific knowledge about the Antarctic environment to help legitimise their control. With today’s increasing threat of climate change, the importance of Antarctica as a scientific hub is ever growing, and the way in which countries engage with scientific research in Antarctica can tell us a great deal about the contemporary geo-political scene, especially surrounding climate change.

It seemed that Howkins was seeking to expose this mutual relationship between the science of climate change and the politics around it. ‘In Antarctica, science is very explicitly political’, comments Dr Howkins. I wonder if the science dictates the politics, or whether instead the politics drives the science?

Why do so many countries want a piece of this frozen wasteland? I ponder. Antarctica is not a country, nor does it have an indigenous population, or a government; it is the coldest, driest and windiest place on earth. Antarctica is inhuman. It begs the question again – why have Britain, France, Norway, Australia, New Zealand, Chile and Argentina all drawn their own lines on Antarctica’s map, territorially claiming parts of it?

'The legacies of earlier imperial expeditions remain, hanging in the air like a looming fog.'

The unsurprising answer is, dare I say it, resources. There is no doubt of the continent’s huge abundance of oil. Some predictions suggest Antarctica could hold more than Kuwait or Abu Dhabi. Antarctica’s waters also offer huge economic potential through fishing. Despite this, the entirety of Antarctica is set aside as a scientific preserve, enshrined by the 1961 Antarctic Treaty. Yet it is difficult to predict what will happen in 2048, when the protocol banning Antarctic prospecting – the process of exploring a region’s mineral deposits - comes up for renewal; by then, could we be a desperate, energy-deprived world willing to make a different decision?

I can’t help but wonder how this will play out in the future. Seven countries have laid claim to parts of the South Pole and in total 53 nations govern Antarctica. As Leslie Hook reported – the FT’s environmental correspondent – ‘At stake is the last pristine continent, one that contains the world’s largest store of freshwater, huge potential reserves of oil and gas and the key to understanding how quickly climate change will impact the world through rising sea levels’.

As Howkins swigs back his last drop of coffee, he tells me that part of his work involves interviewing scientists who have been to Antarctica, and recording perhaps a more humanised perspective of historical work in the South Pole. As I sit opposite him, it occurred to me not only how important his work was, but also how hugely absorbing it must be. All encompassing.

‘Lake Bonney has risen by eighteen meters in the past one hundred years.’ Howkins says. ‘That’s higher than this building. At the moment climate change is certainly driving this research. I think my role as a historian on trips like this is also to give the scientists some perspective. It’s a very complicated story and acknowledging that is important.’

We talked about how the legacies of earlier imperial expeditions remain, hanging in the air like a looming fog; how the ‘Heroic Age’ of Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, and Ernest Shackleton, fuelled by national pride, all competing to be at the forefront of science and exploration. To what extent is this still driving science in Antarctica? Has the focus shifted away from covetous exploration and towards covetous economics? If so is this still equally damaging to an increasingly fragile continent?

For someone so involved in such an absorbing and hugely consuming project, I was sceptical about the extent to which Howkins could fit time for other things in his life. But he does. Indeed, as a part of the Iona Christian community in Scotland – a community with a strong commitment to ecumenism, peace and social justice issues – the charismatic man is also in training to become a self-supporting minister within the Church of England.

It’s clear this is someone who’s work – indeed his life – is firmly rooted in the regions he’s known. The wild beauty of the Hebridean island of Iona connects its members closely to the natural world, and indeed this is a pivotal part of their movement.

We discuss how the growth of secularisation and science over the past two hundred years has changed the way in which humans interact with the natural world; a shift that saw people assign environmental changes to the rationale of science, instead of the actions of God. I ask Howkins if there is ever any conflict between his religious beliefs and his scientific research.

'Religion and environmental history are interlinked, it’s fascinating.'

‘Not at all’ he replies. ‘For me, they are totally compatible’. There’s a great sense that Howkins’ beliefs in both religion and science are beautifully linked by a greater epistemological understanding of our world. It strikes me how well considered he is about everything, as though it has all been carefully thought through and deeply pondered over.

The Iona community seems to allow him to connect on a more profound level with his work in Antarctica. ‘It gives me adeeper understanding on human relations with the natural world and how they have changed. And also how we fit into it’.

In reflection, two things stuck with me after my interview with Dr Adrian Howkins. The first was how all the interests in his life seem to be wonderfully woven together, like a beautiful tapestry, not just existing alongside each other, but subtly complementing their presence. History. Religion. The natural world. All pervasive and full of essence. And the second. Well the second thing that stuck with me was that perhaps we should aim to get to know our lecturers just a little bit more than just as our lecturers. After all, they’re human too, right?

Featured Image: Epigram / Adrian Howkins