By Lucy Mahony, Fourth Year, Bioinformatics

A new study involving researchers from the University of Bristol, has highlighted an important distinction between African and Amazonian forests in their future ability to soak up carbon dioxide. This difference will be indispensable for effective future policy.

So far, tropical forests have been referred to as carbon ‘sinks’, due to their ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. As we continue to pump CO2 into the atmosphere, forests have conveniently removed approximately 15 per cent of these anthropogenic emissions.

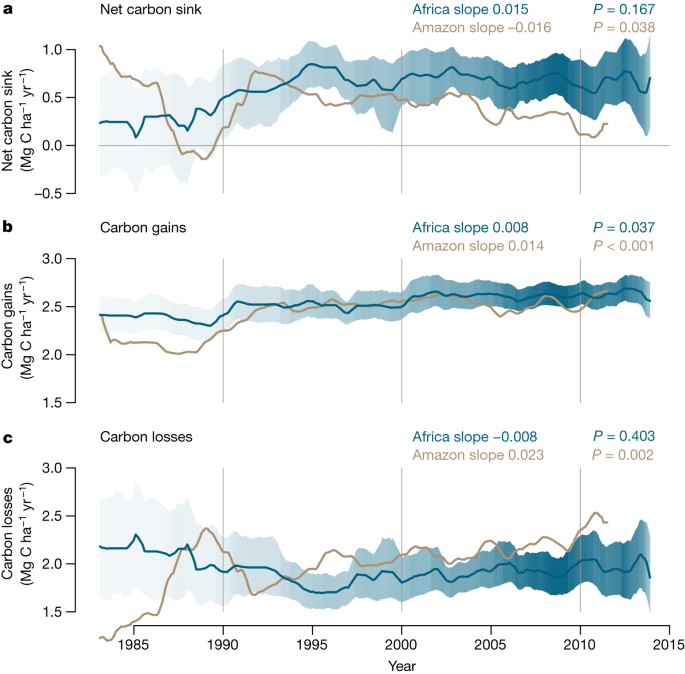

The amount of carbon that African forests can sequester (ie. store) via photosynthesis, has been relatively stable for the past three decades. On the other hand, since the 1990s the amount Amazonian forests can sequester is on the decline. This difference is thought to be a result of higher death rates of the Amazon caused by heat and drought.

Understanding these differences are vital, as tropical forests account for approximately one-third of Earth’s terrestrial gross primary productivity – the ability to convert atmospheric carbon into organic compounds – and one-half of Earth’s carbon stored in terrestrial vegetation. As such, even small changes to the functioning of tropical forests can have a huge effect on the global carbon balance.

Many current climate models have made the assumption that we can rely on current tropical forests as carbon sinks for decades to come. This research adds to the scientific consensus that the tropical forest carbon sink is set to end sooner than what even the most pessimistic climate-driven vegetation models predict.

On the 22 and 23 April 2021, US President Joe Biden brought together presidents and leaders across the globe to attend the online Leaders’ Summit on Climate, in hopes to set up a concrete plan to tackle the climate crisis. Despite hope for a Brazil – United States agreement on Amazon rainforest protection, one failed to precipitate.

The US, along with other nations, are prepared to provide funding to actively protect the Amazon from further deforestation. However, President Joe Biden is not willing to hand over these funds unless President Bolsonaro is clear in outlining a plan to reverse the ongoing damage. It seems that negotiations are currently at a standstill.

Despite five African leaders being invited to the conference – Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Gabon, Kenya, Nigeria and South African – African tropical forests were not centered in the conversation. A summary of the current climate goals of these countries can be read here.

Earth’s lungs are shrinking, as humans keep interfering with the Amazon’s ability to regrow

£10 million invested to guide the UK into a greener future

In response, Greenpeace Africa Congo Basin Forest Campaign International Project Leader, Irene Wabiwa said ‘Congolese and other Central African governments must shift their support from industrial destruction and degradation of the rainforest towards collaborating with and empowering local communities and Indigenous People, who remain the best guardians of the forest and its rich biodiversity. Community forest management plans need national and international backing, in order to pick up pace and become recognised as the local system of ownership.’

If we are to limit global warming, we must protect both African and Amazonian tropical forests, as well as push for an earlier date to reach net-zero anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Featured Image: CIFOR / Patrick Shepherd

Did you watch the 2021 Leaders' Summit on Climate?