by Epigram Film & TV

To mark International Women's Day on March 8, our writers wrote about some of the key female figures of the film industry, both past and present.

Greta Gerwig

Chosen by Daisy Game, First Year, English

IMDB / IFC Films

Frances Ha (2012)

Patch is the kind of guy who buys a black leather couch and is like, ‘I love it’. Introducing Frances Ha(lladay): spiky, awkward and ‘too tall to marry’, Greta Gerwig’s Frances is an antiheroine of epic proportions, starring in the perfect nothing-really-happens-but-everything-REALLY-happens narrative. ‘Dumped’ by her best friend Sophie, Frances is left to her own comically inefficient devices. Flying to Paris with a credit card she received through the mail, moving in with ‘artists’, Benji and Lev (air quotes fully implied), and working a summer job at her old college (at the age of 27), funny and sad in equal measure, Frances Ha is a film about growing up, and shrinking back down again. ‘I’m not messy, I’m busy’; ‘I have trouble leaving places’; ‘but your blog looks so happy’: gloriously funny and stunningly relatable, Frances Ha is the ultimate celebration of confusion, jealousy, and the busy, messy lives we lead.

Natalie Kalmus

Chosen by Leah Martindale, Third Year, Film & TV

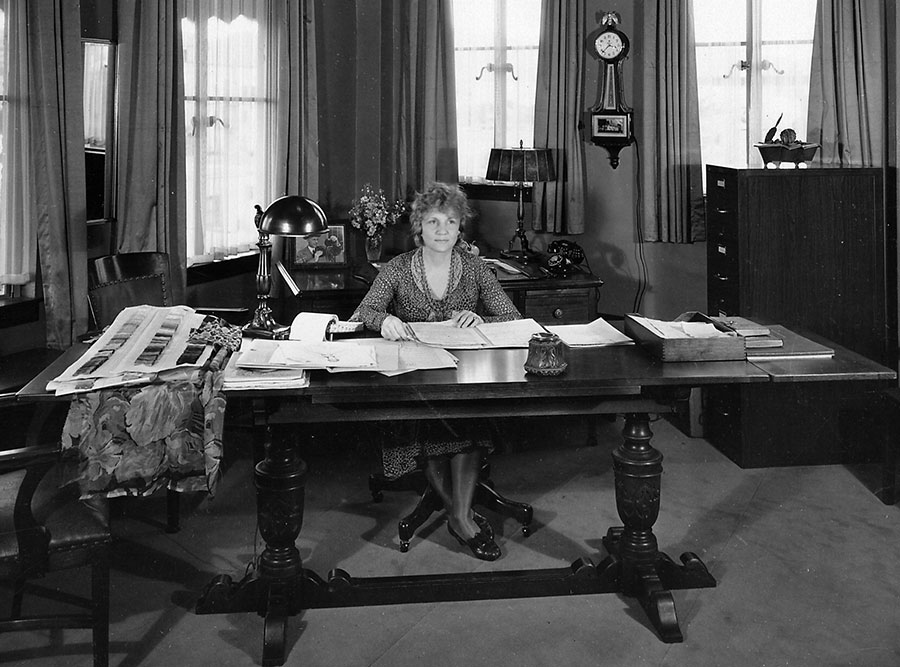

Courtesy of American Stock Photography

Various Technicolour films (1934-49)

While cinema’s feminist icons are often recognised as the actresses, directors, and characters who shape our viewing, little is spoken of the figures who paved the way for women’s place behind the camera. Kalmus is shamefully unknown, despite her credits as ‘color supervisor’ on nearly every Technicolor film from 1934-1949. Her dedicated work ensured the success of the sets, costumes, and lighting synonymous with Technicolor. Kalmus also wrote guides and critiques which became cornerstones for cinematic colouration. While she was not always popular, director Allan Dwan notably called her a ‘bitch’, that is arguably the price women had to pay for being unapologetically good at their craft. I’d happily be a bitch if it gave me the talent, brass-balls, and artistic eye of colour’s unsung hero.

Agnès Varda

Chosen by Siavash Minoukadeh, First Year, Liberal Arts

Michael Kovac / Getty Images

Ulysse (1983)

Faced with a career as prolific as Agnès Varda’s, it can be difficult to find a way in but Ulysse, her 1983 short film, is a good starting point. As with many of Varda’s films, it looks at how fact and fiction interact. The premise is simple: Varda returns to a photo she took of two men thirty years ago to see what has changed.

Characteristically, Varda does not avoid self-examination and her role as storyteller is also questioned. Her female gaze of male nudes demonstrates how radical Varda’s vision is, providing a breath of fresh air in a cinema establishment that still heavily favours men. She balances these theoretical questions with more emotional moments, with her subjects and herself reflecting on how they remember their youth. Ulysse captures what makes Varda’s films so enduring, showing both a serious interrogation of the nature of filmmaking without losing empathy and warmth.

Viola Davis

Chosen by Ella Alalade, Third Year, Ancient History

Thos Robinson / Getty Images

Doubt (2008)

It’s hard to find a role where Viola Davis doesn’t excel. She received her first Oscar nomination for ‘Best Supporting Actress’ for her role in Doubt. An actress with incredible range, she brings plenty to the role of a dismissive mother, whose son has an inappropriate relationship with a Priest. In her first scene, reserved and already aware of the situation, she is protective of her son to the Principal Nun (Streep). Davis, in her posture and tone of voice, portrays the uncertainty and defensiveness but also the willingness to be ignorant. In the last moments, we see her more emotional while discussing the abuse from his school and Father, as the son may be gay. Davis captivates with her facial expressions and mannerisms to tell the story of her character in only a few minutes. A scene with such emotion is rare.

Geena Davis

Chosen by Sophy Leys Johnston, Third Year, English Literature

IMDb / MGM

Thelma & Louise (1991)

Often hailed as the foundation of a groundbreaking feminist manifesto within film, Thelma and Louise continues to remain one of Geena Davis’ finest performances. What starts out as an innocent road trip, rapidly escalates into a journey of crime-committing, cop-fleeing chaos after Louise (Susan Sarandon) impulsively murders chauvinistic, would-be-rapist, Harlan. As one half of the iconic duo, Davis’ performance perfectly encapsulates Thelma’s arc from “sedate” housewife to alarmingly confident, gun-wielding robber.

Emerging from her entrapping marriage, Thelma is thrust into a world of independence and freedom, perfectly subverting the constructed gender roles of a typically male dominated cinematic genre. Just as her character achieves, Davis herself has the ability to diminish the performances of her male co-stars, often side-lining their comparatively two-dimensional characters to entirely dominate the screen. With a memorable mix of relatable fear, enviable authority and sharply delivered comedy, alongside an equally thrilling performance from Sarandon, it is no surprise that the two protagonists reaped a box-office success upon release and continue to withstand universal acclaim today.

Lynne Ramsay

Chosen by Ewan Marmo-Bissell, Second Year, History

Vittorio Zunino Celotto / Getty Images

You Were Never Really Here (2017)

Lynne Ramsay last year directed one of the most visceral and violent films I have ever seen, and yet every scene is captured with an inherent beauty despite the story’s bleak and at times horrific outlook on the world. You Were Never Really Here is a psychedelic, tumultuous journey through a depressing criminal underbelly of sin and oddly detached violence that Ramsey captures through more unconventional means. You can feel every slash and pummel but you as a viewer are very often removed from the violence itself. The other key players in the film are Joaquin Phoenix who plays the mortally depressed Joe and Jonny Greenwood whose wild and restrained score soundtracks Joe’s journey with everything from soothing violins to clanging drum sequences.

Snubbed entirely from the awards season, You Were Never Really Here was a masterpiece that exemplified everything genius that Ramsay had so often been able to pull off. Finding that dichotomy between beauty and a relentless horror. Her influences from the horror genre are most obvious in this, her fourth film. It’s terrible to watch at times, out of fear or unsteadiness as to what lays around the corner, or through the door. It’s Ramsay’s finest work, and the hardest to watch.

Merie Wallace / Courtesy of A24

Which other women do you consider icons of film and television?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter