By Leah Martindale, Third Year Film

The first of a two sided argument exploring the effects of film violence on real life crimes and attitudes, here it is argued that cinema is one of the least significant factors which may increase aggression levels.

Violence has been an inherent element in cinema since its inception. Much of the earliest moving pictures from the 1890s display crude and childish slapstick humour. As of October 21, from the top five grossing films of all time, only Titanic (1997, dir. James Cameron) could be described as featuring no violence - and hundreds of people still died.

When we look at violence levels related to violent cinema, it’s clear the two aren’t correlated. A 2014 study at a New York hospital concluded that while violent scenes affect brain activity and behaviour, the reactions are vastly different depending on your personality - whether you were already a calm or aggressive person.

Epigram / Patrick Sullivan

Levels of violent crimes more often relate to socioeconomic factors, and the ghettoisation of certain groups by postcode. If we are to tackle issues of violence in cinema and its correlation with social groups’ levels of violence, we flirt with a cinematic eugenics eradicated a depressingly short time ago - see the South African Population Registration Act of 1950, and its regulation of cinema.

Of course, our old friend racism always lurks in the shadows of such discussions. The scaremongers of the anti-violent cinema brigade were rarely fearful of Terminator (1984, dir. James Cameron) inspired vigilante squads of white men taking to the streets, but Spike Lee’s relatively less violent Do the Right Thing (1989) has famously been ranked as one of the most controversial films of all time.

Why might the possibility of black people rioting against a police officer murdering a brotha, or coming Straight Outta their hometowns incite more fear of the pervasivity of cinematic violence than with other, lighter demographics? It is truly a mystery for the ages.

IMDb / Kick-Ass 2 / Universal Pictures

Actors and filmmakers, while artists, still need to show humanity publicly. Jim Carrey tweeted ‘I did Kick-Ass [2, 2013] a month before Sandy Hook and now in all good conscience I cannot support that level of violence’. Carrey’s Grinch-like, three-sizes-too-big heart is admirable and understandable, but I’d say misguided.

If we censor ourselves of all imaginable evils, when they occur in reality we would never do anything. Carrey’s purposeful detachment from the project shows a bold acceptance of the artist’s culpability and responsibility for their art. I cannot, in good faith however, accept this detachment.

Famed French expressionist artist, Henri Matisse, said that creativity takes courage. Surely that includes the courage to show the reality of the world’s aggression, in the full spectrum of realism in film?

Epigram / Patrick Sullivan

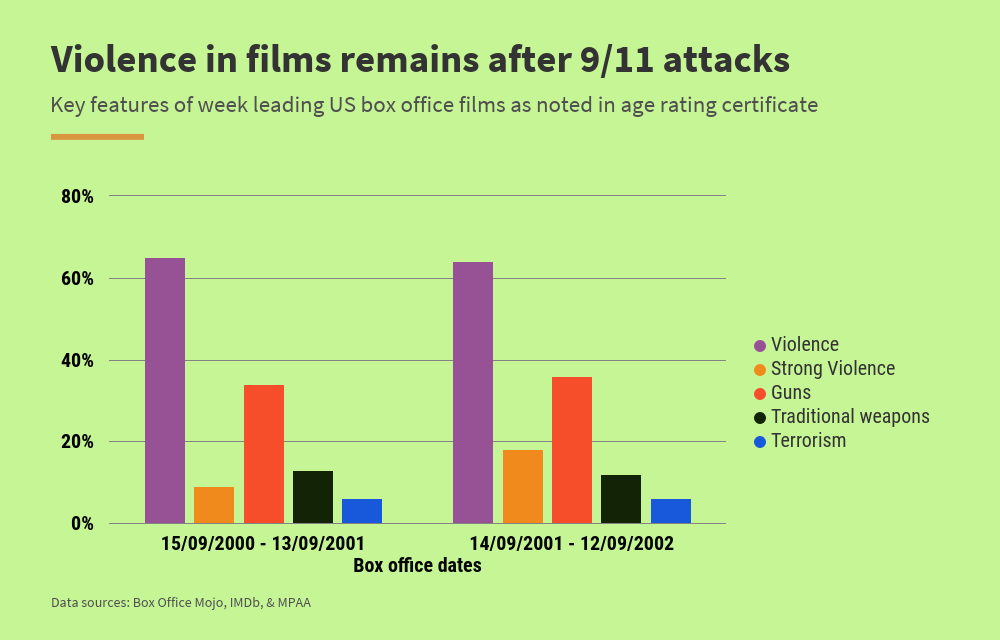

After 9/11 in 2001, it was theorised that violence in American cinema would have a drastic decline. However, in the years that shortly followed, releases included classic action films such as Minority Report (2002), The Bourne Identity (2002), Kill Bill (2003), and a plethora of superhero films. Action, and inherently violence, became the country’s strongest rallying force against the fears of an insatiable and unstoppable evil.

In a world where you could go to work one morning and simply never return, burnt to death in your seat or die leaping from a crushed building, the idea of superhumans, spies, and badasses, was a nation’s saving grace. Looking back at the thrillers and Hammer Horrors that came out of wartime Britain, you can tell the sentiment is hardly new.

Read the other side of the argument here!

Featured Image: IMDb / Minority Report / 20th Century Fox

Collage Images: IMDb / The Terminator / 20th Century Fox // IMDb / Do The Right Thing / Universal Pictures

Would you rather see the amounts of violence in film curbed or even censored out?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter