Josh Peleg reflects on the reasons behind NME's decision to cease the publication of its print edition.

NME died a slow and aggravating death. Having gone from a paid publication, to a free print, to no print at all, it’s a sad state of affairs for a magazine which is the wallpaper of so many bedroom walls. But why is this brand, which used to be the highest selling music paper in the 1970s and have the biggest standalone music website in 1996, on such a depressing decline to disappearance? The reasons are many. This is the first time I’ve gone out on a limb to write an article about something I love, because watching NME drown in this gloop of malnourished 21st century pop culture hurt me on a personal level. Spare me five minutes of your time and I’ll take you though a well reasoned response to this inevitable event of 2018.

Contrary to popular to belief, I do not think that the progression of music itself is to blame. The common argument normally takes this kind of form, ‘How can a Rock n’ Roll magazine survive in a rap & pop dominated musical world?’. The answer is two Cs: counterculture and controversy; elements which the magazine is lacking in the modern age. NME famously has golden boys; these are bands or artists which are always given good reviews, dominate the front pages and can seemingly do no wrong. To name a few, there are The Libertines, Arctic Monkeys, Noel Gallagher, Pete Doherty (solo) and Morrissey. Throughout their good and bad days these artists are repeatedly praised and glorified as if they could do no wrong. This stance from NME devalues it’s integrity as a publication that should supposedly adopt an un-biassed view towards its subjects. Many of the reviews feel like they come from salivating fanboys (and girls) who kiss the feet of their idols. This is also seen in the way NME reports on news and gossip. Full articles about the state of Alex Turner’s facial hair (which happens to make him look like a homeless Dubliner) and one titled, ‘Liam Gallagher wishes Morrissey a ‘miserable Christmas'', makes me want to renounce any love of guitar music and begrudgingly pledge my allegiance to Nicki Minaj.

“The margins for error just got slimmer and slimmer until the margins ran out.” I spoke to a lot of people about what killed the NME https://t.co/dVKLYWlzKm

— Laura Snapes (@laurasnapes) 14 March 2018

In my opinion, a Rock n’ Roll magazine should praise its gods as much as it exorcises demons, brings me to another point about favouritism. An opinionated magazine should diss, cuss and chastise that which goes against its ideology. Mindless and superficial pop culture should be demonised and made a villain of the type of music that NME is otherwise presenting. I say this in the interest of increasing circulation numbers. It’s a well known fact that Rock n’ Roll and Punk has always flourished by presenting itself as an antidote to a popular illness. Be it the establishment, politics or top knots, there has always been a force that Rock n’ Roll has sought to oppose, and it was in the friction of this hostility that NME used to flourish. During the 1970s, NME held its highest circulation numbers, and as voted by NME users, 8 of their favourite covers were in this period. These included the likes of The Clash, The Sex Pistols (twice), John Lennon and Syd Barrett, all of whom were controversial figures.

Controversial figures revel in the public eye, but none more so than politicians. Publishing an article about ‘Jeremy Corbyn’s heroic speech’ at Glastonbury 2017 was funny, savvy and in touch with the interest of modern-day festival goers. However, putting Jeremy Corbyn on the front cover of the June 2nd edition is like running into a knife fight with a rubber pink dildo; it is NME entering a political arena with only musical credentials to their name. Being anti-political parties is cool and rebellious, despite us living in a time when it is increasingly respectable to hold political opinions. However, voraciously supporting a single party is a predictable partisan attitude that I am specifically looking to avoid when I pick up a copy of NME.

If the magazine wants to demonstrate a personal opinion on the subject, then I believe that they should do it through the focalisation of a band. This is something that they have done, but not enough. For example, the band Slaves, a punk-rock duo with a left political leaning (famous for songs such as ‘The Hunter’ and ‘Cheer Up London’), have violent yet existentially driven songs that chastise the political system and demand action from their listeners. In their fight against apathetic Londoners, I feel exempt, having already sacrificed a chip of my front tooth for them (there’s a white spec of enamel buried in a field somewhere in Glastonbury if anyone fancies retrieving it for me).By placing Slaves on the cover, which they have done twice now, it channels a political option to its readers without ultimately aligning the publication itself to a certain standing point.

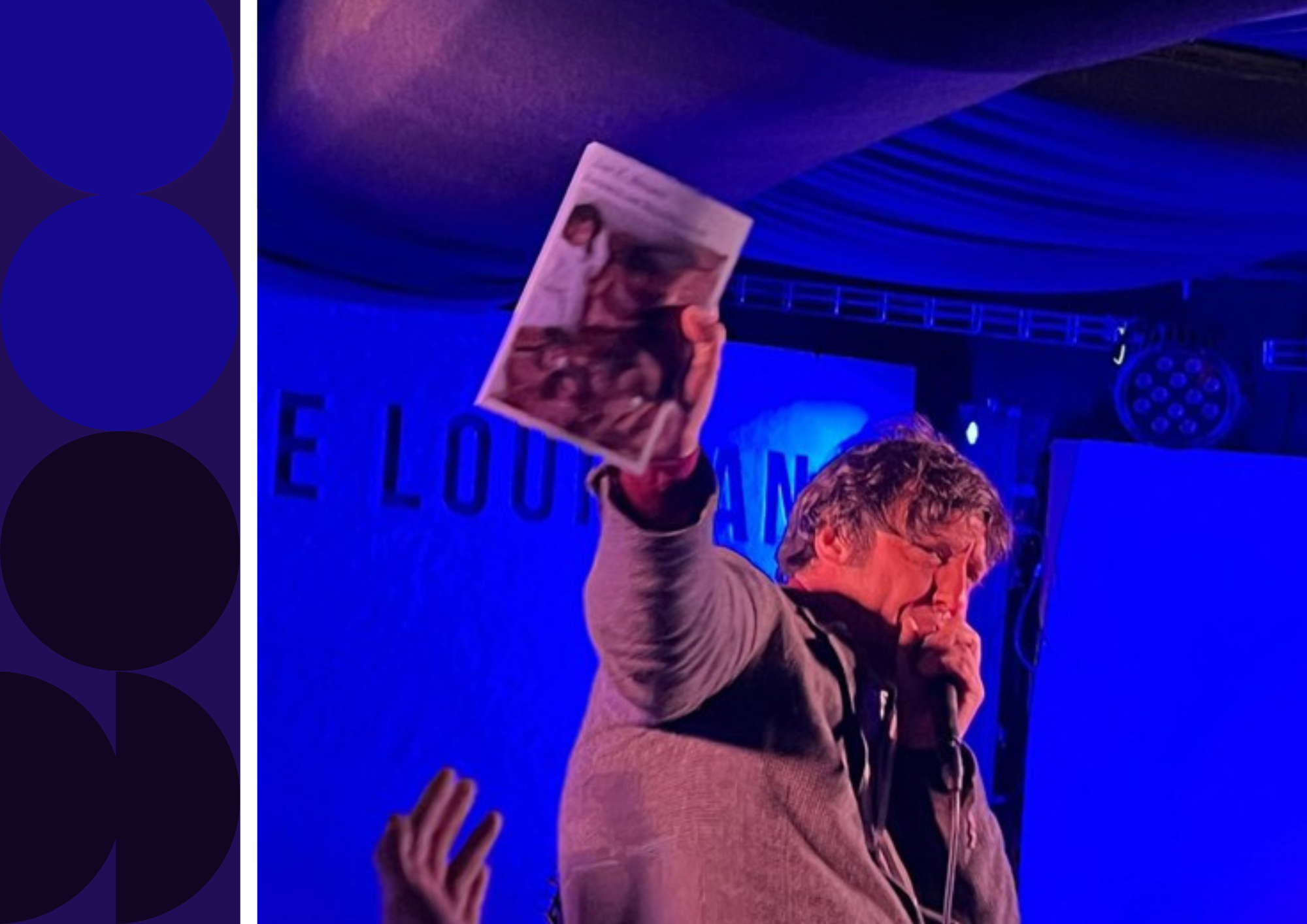

My final point is probably the most inevitable; it involves tangibility and the internet. Tangibility is underrated; holding a picture of Noel Gallagher (or anyone else) in your hands to either wipe your ass with or pin it up on your wall is a defining element of any teen forming their musical taste. NME has had some absolute bangers on their cover pages, and this ‘in your face’ effect is completely lost on their website. If they intend to survive as a teeth-gnashing defender of ‘the good ol’ days’, or as a baton-wielding crusader of the future then they have to represent that feeling on their website. The worldwide rise of online journalism and decline of paper publications is the most saddening aspect of the future, but also the most inescapable.

But allow me to get nostalgic for just a moment. Waking up on a Friday morning, in the final few years of secondary school, I would grab a few coins from my desk drawer and take the tube into the city (London). The hours would swim lazily by, until I could bunk double Spanish just before lunchtime. I would slip out via the front entrance, being sure to duck under the classroom windows as I walked towards Blackfriars. It was a right of passage, a pledge of allegiance to what NME represented for me, and thousands of others. NME was a cool older brother. The one who smoked without mum knowing, snuck out to go to gigs and only needed mates and a cracked Fender Strat to be happy. Bunking school to spend my lunch money on NME seemed the only thing cool enough I could do to impress him.

So… Dear NME, if you’re not gonna give us dreams of being in a band or the balls to tell someone to ‘Fuck Off’, then you may as well make your bed of crumpled old editions under a London Bridge, lie down to sleep and never wake up.

Do you agree with Josh? Do you miss NME in print? Let us know...

Facebook // Epigram Music // Twitter