By Sarah Dalton, SciTech Editor

SciTech Editor, Sarah, explores how technology usage has changed amongst students as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the colloquial misuse of the term ‘addicted’, 30 per cent of people in our digitalised world are estimated to suffer from a form of problematic use of the internet, according to the International Journal for Neuropsychiatric Medicine.

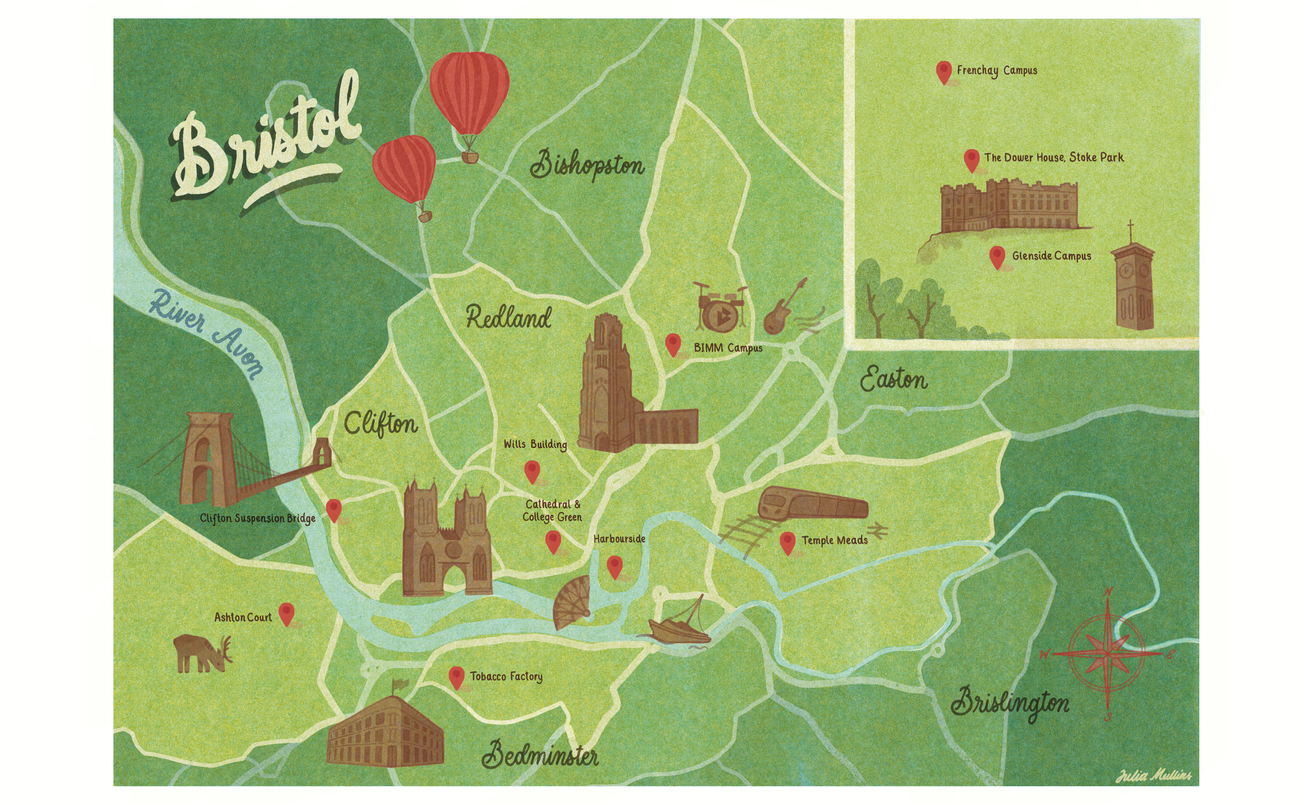

School, work, news, entertainment – the last century has seen all of these platforms of daily living transferred from paper to devices. However, with the pandemic forcing students into a virtual world like never before, just how have University of Bristol students fared? Epigram went to investigate.

In a survey of 227 current University of Bristol students, an astonishing 91 per cent reported that they spend more time on technology now than before the pandemic, confirming assumptions that technology usage has increased amongst students. However, a high technology usage does not necessary indicate a technology addiction, unless this is accompanied by a lack of control over a behaviour that causes psychological or physical harm. Compulsivity and potential for harm must also be taken into account.

When asked how often they felt the need to check social media, 75 per cent of University of Bristol students responded with every one to two hours, with a mere 2.6 per cent of students checking just once a day. This could be interpreted to mean a strong element of compulsivity.

‘I think [social media] is having a real impact on people’s ability to think critically’

However, when surveyed on which app they used the most before and after the pandemic, the use of Instagram, Facebook and Youtube all dropped, whilst Tiktok proved to be the champion of our pandemic, shooting up by a whopping 31 per cent.

So, what is it about these apps that makes them so addictive? One potential answer, posed by social psychologist Adam Alter, is their lack of stopping cues. A stopping cue is defined as a ‘signal that it is time to move on’. The ending of a chapter prompts you to ask if you wanted to read on or put the book down and the end of a radio show prompts us to ask if we want to switch off or listen on.

91 per cent of University of Bristol students spend more time on technology now than before the pandemic

Interestingly, media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram have removed these stopping cues, instead becoming a scrolling stream of media which never reaches an end point. As a result, hours of our lives are scrolled and swiped away often with little sense of the passing of time, and the detrimental impact of this on mental health is clear.

Yet, despite the figures, is technology always a hinderance for the modern student? Not necessarily. As one Third Year Biochemistry student told Epigram: ‘It’s really easy to get distracted by social media, but the resources technology provides me with in terms of accessibility to research, books and note taking far outweighs the costs.’

Why we should be talking about AI in higher education

Building a PC on a student budget

Reflecting on the situation within the humanities, Third Year English Literature student Sanjana Idnani added that ‘I think technology, especially social media platforms like Twitter, have taken the nuance out of situations. People, brands, journalists, politicians, all think about fast engagement over slow thought now and I think that’s having a real impact on people’s ability to think critically.’

Featured Image: Epigram/Sarah Dalton

How have your technology habits changed since the COVID-19 pandemic?