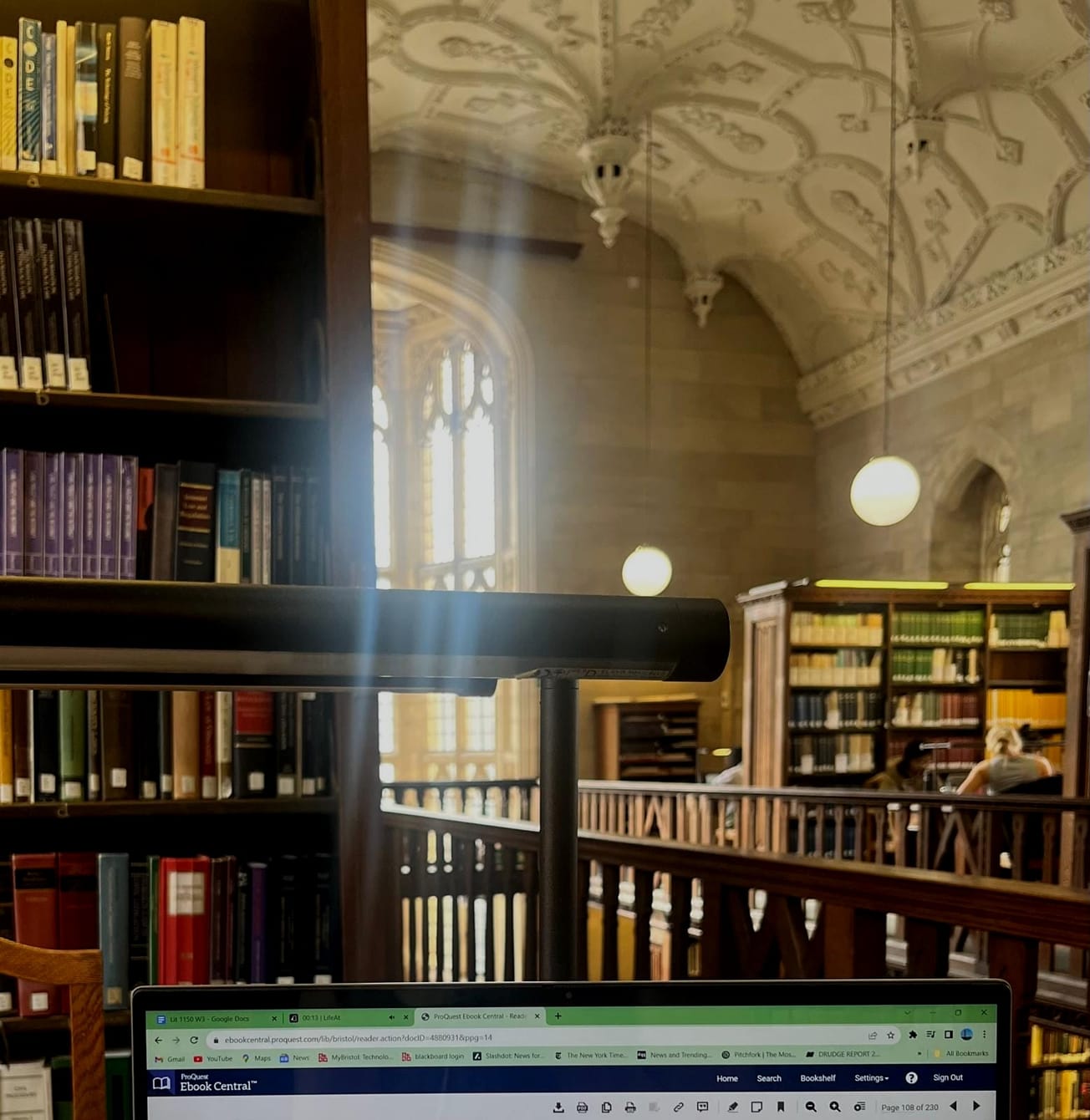

An anonymous writer adds to the debate about the renaming of the Wills Memorial Building.

As a European, white person, should I chime into this debate? Those on the extremes of both sides of the argument may have their respective, emphatic answers. The “common sense” conservatives would say: of course I have a right to express my opinion, however inflammatory and nativist I want to be – this is a “free” society. On the other hand, those people who Trumpists and Alt-Rightists would call “snowflakes”, could understandably argue that my perspective is not adding much to this debate – I am not the victim here.

Does naming the University’s key building after someone who profited from the proceeds of slavery amount to glorification?

There is force to this argument – if, and I’m going to allude to the oft-quoted example, a prominent building were named after Hitler and descendants of his main victims (Jewish people, Slavs, LGBT, disabled people, Roma, non-Arians etc.) were not given a strong voice in the debate, most people would see an injustice.

Therefore, I recognise the need to tread cautiously in this debate, as I am not a victim as such. But, as a critical and open-minded person, affronted often by the heinous acts (‘Mau Mau’/response to Indian famines and mutinies/Ireland/hunting indigenous peoples in the land now called Australia/ ‘Rhodesia’…) committed by some Brits in their empire, my opinion carries some weight.

Having established my rights of audience, as it were, I hope now to deal with the substance of this debate. This can be dealt with fairly quickly – we are covering much of the terrain, gone over in the #RhodesMustFall debate. At root, this argument centres on cultural and philosophical tensions.

Firstly, how do we present controversial art? Does naming the University’s key building after someone who profited from the proceeds of slavery amount to glorification, as alleged by the ‘Wills Must Fall’ side? There is a historical debate to be had here about causation. After how many generations do the proceeds of slavery become sanitised?

There is no acknowledgment in the permanent fabric of the Wills Memorial Building to the contribution made by slaves to its construction

This type of question could be multiplied to a macro level – to what extent is the U.K.’s position of (relative) global, financial dominance intertwined with past economic exploitation of the modern ‘Commonwealth’, and with global markets constructed in the Western image at this time, from which we benefit today?

Assuming that there is a causal link between Wills’ ability to endow substantially the University in 1908 and slavery, this brings us back to the core aesthetic issue here. If I am not mistaken, there is no acknowledgment in the permanent fabric of the Wills Memorial Building to the contribution made by slaves to its construction – neither installed during construction in the 1910s and 1920s, nor more recently. This architectural curiosity appears particularly incongruous in modern Britain, which is meant to celebrate pluralism, and can and does often admirably excavate the voices of those written out of the dominant narratives in history.

Please help us end the glofication of slave masters!! - Rename Wills Memorial Building https://t.co/MkQwqsBdn6?

— Katieellie_ (@Katieellie_) March 28, 2017

This fact speaks to the second core issue – offence. The fact that there is more Latin and hangovers from feudalism – veneration of George V – than mentions of slavery, animates the deferential, perfectionist and stratified nature of elite Bristol society in the 1920s. In order to present a more holistic account of how this University was endowed and built, a story which warrants veneration, we could have a permanent, prominent sign explaining the links to slavery in the foyer. The full title of the building could also acknowledge this debt.

Ultimately, you cannot come near to understanding the history of Clifton without understanding the history of the Caribbean. You cannot erase Wills from Bristol’s history, but you can better contextualise his historical impact, reflecting this in the aesthetics.

It is necessary to have an enabling environment where dissenting voices can be heard.

Secondly, is it legitimate to be offended? Dan Hannan MEP protested vigorously the suggestion that Rhodes must fall in Oxford. He argues that it is narcissistic to judge past generations by present morality. But this kind of argument is problematic in two respects. It presupposes that the values and culture of, say, 1920s Bristol were monolithic – everyone was indifferent to the exploitation of Africans and supported colonialism – a grossly simplistic historical perspective.

There were dissenting voices even then, criticising people like Rhodes and benefactors of slavery. So the students’ position is arguably not ‘present morality’; there is indeed continuity here. Relatedly, the reason why there were dissenters even then is because there are some acts which are morally repugnant in any period. For condemnation of these acts to move from fringe to majority views, a consciousness raising exercise, it is necessary to have an enabling environment where dissenting voices can be heard.

Don't hide history - keep it visible so we are aware of it & can learn from it.

I oppose changing the name of Wills Memorial Building. https://t.co/8SD2bx9ioR

— Nicholas Pope (@nick_pope) April 3, 2017

It is, therefore, no accident that acceptance of Britain’s culpability in the murder and exploitation of millions across the ‘Black Atlantic’ for several centuries – arguably state-sponsored until around ‘Mau Mau’ – has increased. This acceptance coincides with the British state tolerating discrimination towards minorities less, evidenced by the raft of non-discrimination legislation since the 1960s. Whether minorities feel like they have more of a voice or stake is not for me to say. The crux here is – who decides whether a practice is so wicked that its historical adherents should be expunged from public veneration?

As the force of the British ‘civilising mission’ propaganda wanes with every generation, the moral imperative to decolonise areas of British public life grows. It is only when we have had a nuanced reflection on Britain’s past, that its version of Vergangenheitsbewältigung may set in.

Featured image: Epigram / Georgia Marsh

Should we rename the Wills Memorial Building? Let us know what you think on our social media or in the comments section.