Content warning: contains extended discussion on suicide

By James Dowden, Co-Editor-in-Chief

‘We need to sort out the confusion once and for all. We need to have that debate. We need to clarify the current situation. If the government feels nothing needs changing, they're saying that the current situation is acceptable. We don't think it is.’

Bob and Maggie Abrahart are determined to make a change.

They are currently campaigning for what could prove to be the biggest legal change to student rights in a generation since the 1970s.

Currently under UK law universities and higher education institutions are not required to provide a legal duty of care to their students. The Abraharts, as part of The LEARN Network, a group of 25 bereaved families who have lost children to suicide at university, are working in tandem with the #ForThe100 campaign group, to fight to change this.

The Abraharts were motivated to help with the campaign following the tragic suicide of their daughter Natasha while studying at the University of Bristol in 2018. Her death sent shockwaves through the local community and raised important questions about legal obligations of responsibility towards university students in the UK.

Natasha was a gifted student who excelled in her physics course. Despite her academic success, she struggled with anxiety and depression, arising from a university requirement to do oral assessments, which had worsened in the months leading up to her death. She was found dead on the day she was due to give an in-person presentation for her class.

Following Natasha’s death, her parents wanted to find out answers. Speaking on the eve of the fifth anniversary of Natasha’s death, Maggie recalls how people tried to deny that there had been warning signs. She notes that ‘the thing that stood out for me was you would hear the story in the press. They would always say nobody knew that there was anything wrong. We looked at Natasha's case and we thought that was not what we are finding in the evidence that was presented. We were in this total vacuum. It’s like your life's been shattered. Nobody is prepared for that experience.’

Following an inquest by a coroner, the couple eventually decided to take matters into their own hands in their fight for justice and began civil proceedings against the University.

In the eyes of the Abraharts, Bristol’s response was cold. As Maggie explains, ‘I would say it feels very empty. They make public statements saying that they're sympathetic to the family. It doesn't tend to feel very genuine when they haven't said that to us.’

Bob adds, ‘They've never admitted anything. They've never said sorry. We publicly asked for a meeting to sit and talk with the senior managers from the University but we’ve got nothing. All we’ve ever met is their lawyers.’

Eventually, in May 2022 the courts ruled in the Abraharts’ favour, on the grounds of provisions made under the Equality Act. The University of Bristol was found guilty of discrimination against Natasha based on her social anxiety disorder and ordered to pay compensation.

However, just months later their world would be turned upside down once more as the University applied for permission to appeal the decision in the High Court in October 2022.

A statement released at the time by the University of Bristol stated that:

‘We would like to make it clear that this appeal is not against the Abrahart family, nor are we disputing the specific circumstances of Natasha's death. We remain deeply sorry for their loss and we are not contesting the damages awarded by the judge.

‘In appealing, we are seeking absolute clarity for the higher education sector around the application of the Equality Act when staff do not know a student has a disability, or when it has yet to be diagnosed.

‘We hope it will also enable us to provide transparency to students and their families about how we support them and to give all university staff across the country the confidence to do that properly.

‘In Natasha's case, academic and administrative staff assisted Natasha with a referral to both the NHS and our Disability Services, as well as suggesting alternative options for her academic assessment to alleviate the anxiety she faced about presenting her laboratory findings to her peers.’

‘However, the judgement suggests they should have gone further than this, although Natasha's mental health difficulties had not been diagnosed. Understandably, this has caused considerable anxiety as it puts a major additional burden on staff who are primarily educators, not healthcare professionals.’

In December 2022 Bristol was awarded the University Mental Health Charter Award by the UK mental health charity Student Minds for its mental health support services and the improvements made to its mental health provisions in the years since.

However, the Abraharts don’t believe the proposed measures have gone far enough and believe that a legal change at a national level is what is ultimately urgently required to protect students.

During the Abraharts’ civil court case, whilst the court agreed that there was a failure by the University of Bristol under the Equality Act, it was also argued that the University should have a legal duty to its students, but on this specific issue, the court ruled against it.

Now the Abraharts, together with other families, are fighting back to change this.

‘I think there's a sense that for many grieving families, it's just too difficult. You've got the advice from the lawyers that you can't go ahead. I think that universities are in a position where if they make things difficult, people will eventually go away. Now we've got a group of families that just aren't going away’ explains Maggie.

They are campaigning alongside other bereaved families from across the country to create a legal change as part of the #ForThe100 campaign, a reference to the approximate number of students who sadly take their own lives each year while at university.

Maggie explains how the families came together. ‘Over the years we've encountered other brave families and some of us are now brave enough to go forward together. No one investigates the death of a child like a bereaved family. They know exactly what happened to their child. We came together and formed a group and we shared our stories. We came up with this commonality, what was needed to save our children. That commonality was a duty of care.’

Bob details how the term duty of care is often misunderstood and its potential significance for students. ‘We're not talking about medical care. We're talking about the sort of care that’s a bit like a moral duty of care. This sort of care should be applied to every decision that's made at university. If I do this, or more importantly in the university's case if I don't do something, how's that going to impact the student body? It’s not about infantilizing adults. You need adult standards for adult students. It's not rocket science. It's so basic but it underpins every decision a university makes. Don't do something which will result in a physical or mental health problem for one or more students.’

He adds that there is currently a gap in the protection offered by the law when students come to university. Currently, students at schools have a legal duty of care towards them and then when they enter the workforce they are also protected there. In Bob’s view, there is a clear loophole when it comes to the legal duty of care for university students, especially given the fact that there is a legal duty of care for university members of staff.

‘There is nothing after that [legal duty of care at school]. When you got a job, employment law protection kicks in. You’ve got a gap. There's your problem. Students are adults so why can't they have parity with adult staff at the university?’

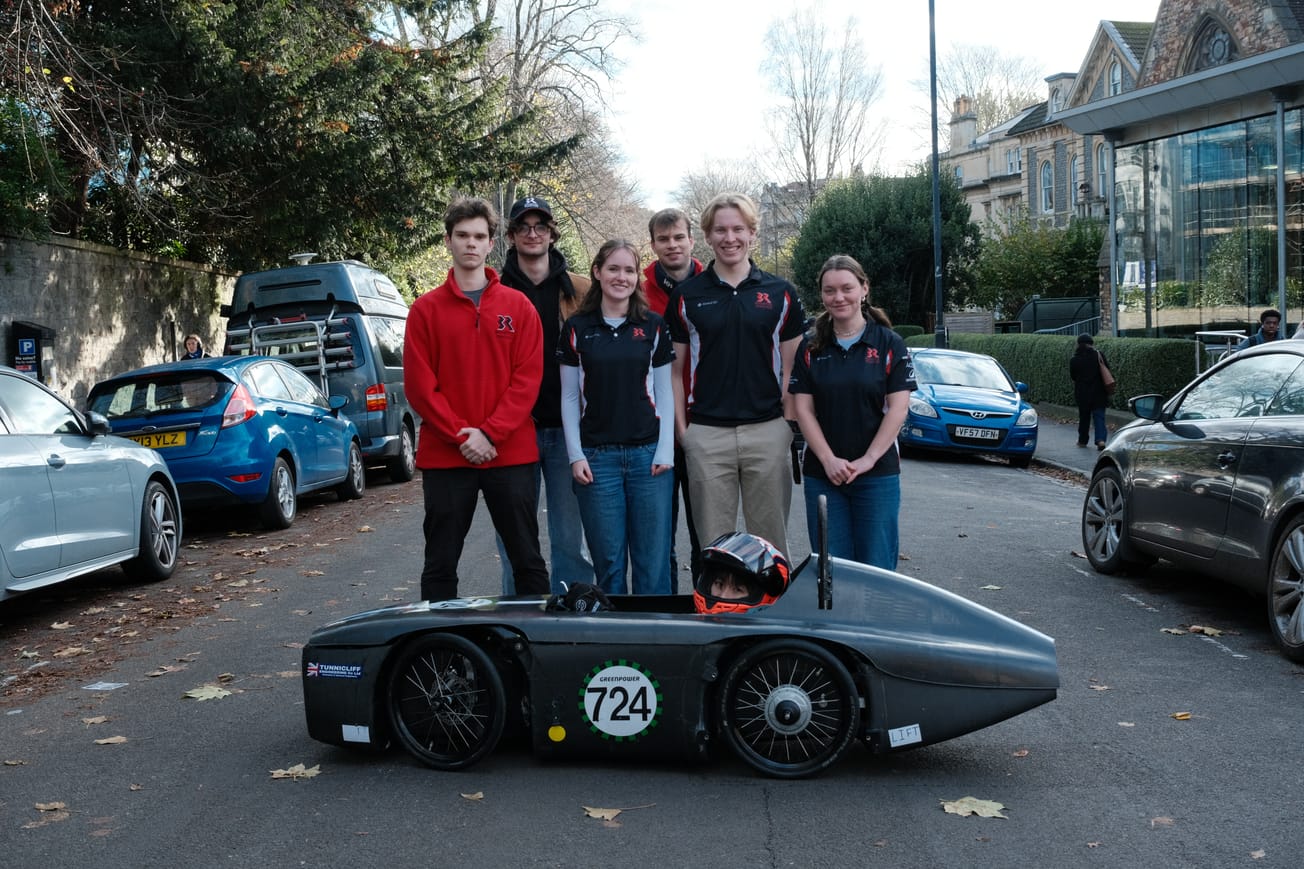

A petition has been launched in support of the campaign which recently passed 120,000 and will now be debated in the House of Commons. The #ForThe100 campaign also held simultaneous candlelit vigils in London, Bristol and Edinburgh on Saturday 4 March as part of the campaign.

In a statement by the University of Bristol on behalf of Vice Chancellor Evelyn Welch stated that:

‘I know just how painful it is to lose a loved one who has struggled with their mental health. The welfare and well-being of our students and staff remain the University of Bristol’s and my own personal top priority. Any student death is a tragedy that hits the very heart of our community. Our thoughts continue to be with the families and friends of those students who have died.

‘While there is always more we can do, Bristol has improved its support for students who are struggling with their mental health. We have made huge strides forward in recent years. While we are never complacent, I have seen impressive models of support and the introduction of a wide range of services that provide crucial early interventions and help.

‘We continue to challenge ourselves to improve academic processes, to understand what services and systems are working well and where potential improvements can be made. We want to work with parents and our broader community to ensure our students are able to access support to enable them to thrive at the University of Bristol.’

Rounding off our conversation Bob says how the road to justice has already been long and draining but alongside Maggie and many other families, they will continue to campaign until meaningful legal change occurs.

‘We've spent four and a half years to get to this point and getting a new law through parliament could take another four and a half years. It'll probably be the end of the task we set ourselves. It will be a sense of justice.

‘How many people are suffering in the meantime? This is four and a half years, nearly five years. These changes should have been made shortly after Natasha died. Everyone knows what happened. We've had to drag it out of the university and it's taken years and years. It's faced massive resistance.

‘It's a bit of new territory because we're all pretty worn down now. We would actually quite like to go away but we’ve got unfinished business so we can't. What needs to happen is a wake-up call up to the system to do what's needed to be done.’

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To sign the petition for universities to provide a legal duty of care to their students click the following link: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/622847/signatures/new

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Where to go for support:

To seek support within the University, students are encourage to access these services:

Students can request wellbeing support by completing a simple Wellbeing Access form, by emailing wellbeing-access@bristol.ac.uk or calling 0117 456 9860 (open 24 hours)

Multifaith Chaplaincy: call 0117 954 6600 or email multifaith-chaplaincy@bristol.ac.uk

Students' Health Service: 0117 330 2720

Students may not always be sure about what kind of support they need – to explore what might be helpful, please complete the form, telephone or email Wellbeing Access who will be happy to help.

Other student support services include:

· Young Minds https://youngminds.org.uk/

· Nightline https://www.nightline.ac.uk/want-to-talk/

· Papyrus https://www.papyrus-uk.org/ 0800 068 41 41

· Student Minds http://www.studentminds.org.uk/findsupport.html

· Samaritans Step by Step: 0808 168 2528 / stepbystep@samaritans.org

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------