By Charlie Graff, MPhil English

Almost everything in Bristol was built from the wealth obtained by extorting the labour of enslaved Africans between the 17th and 19th centuries. The practices and ideological constructions of colonialism survive in Britain and around the world to this day, articulated in different forms and exercised by novel means.

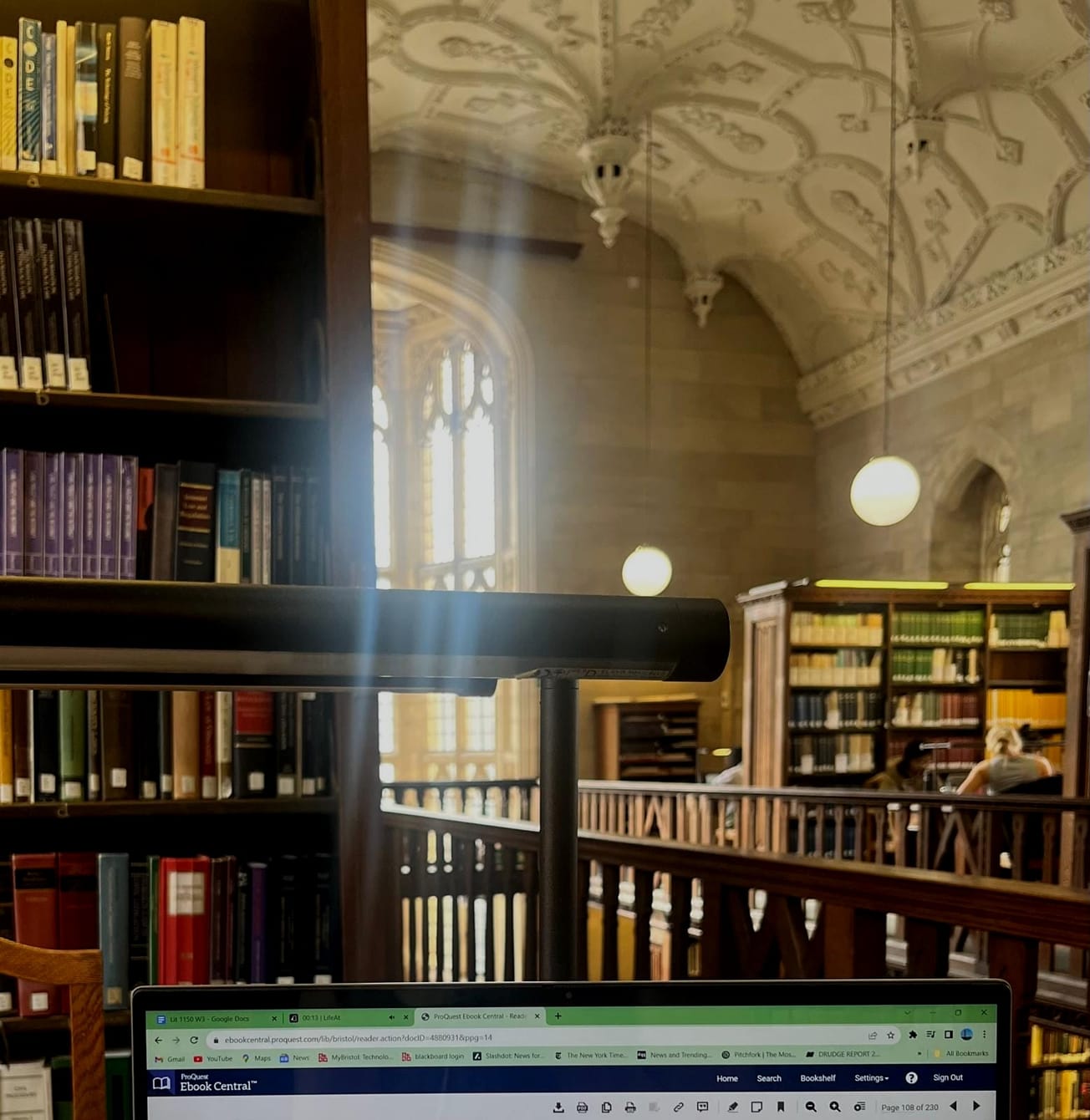

One of the places this is most evident is Goldney Hall: even if you changed the name of this place, a cursory glance around the grounds, with its lead statue of Hercules and mock Gothic tower, could not fail to remind the casual observer of how such a place came to be.

The foundations of the University of Bristol can be traced back to the establishment of the Merchant Venturers' Technical College in 1595, a school devoted to training the navigators upon which colonialism depended. The university received its royal charter in 1909 with the help of the Wills, Fry and Colston families' generous sponsorship. All three families, of course, gained their wealth in connection with slavery. This sponsorship is commemorated by the four panels of the university logo: a ship framed against a tower and the heraldic symbols of these three families.

The university believes it can adequately address its legacy by changing Colston’s emblem for a book and dedicating £10m to a ‘Reparative Futures’ campaign. In an interview with the BBC, student Lisa Inneh said, “[We're] seeing institutions throwing money at a problem but they're not really saying what they're going to do with it.” The university has said that the money will go towards “work[ing] with staff, students, and local communities to ensure the full stories of the institution’s origins, both positive and negative, are made more visible.”

Since the negative stories about the university’s relationship to slavery are so vividly palpable in this city, one wonders how much of the £10m the university intends to spend on promoting positive stories about its origins. At present, the university’s statements seem particularly keen to focus on the fact that it only “indirectly” benefited from slavery. The university seeks to remind students that its wealth stems from “donations originated from individuals or organisations whose wealth can be associated with goods that were produced by enslaved labour but who did not actively participate in enslavement.”

One way to frame the question of renaming could be this: Has the University of Bristol earned the right to assert that it is not the same kind of institution as the one it evolved from? I ask this question in view of the statement released by the Bristol Beacon, formerly Colston Hall, on the topic of its renaming. The statement described the changes as "a fresh start for the organisation and its place in the city". Does UoB deserve a fresh start?

Ships have been traded for aircraft and the navigation college has been transformed into a 21st-century engineering school, but the relationship between Bristol’s industrial centres and the global arms economy as well as the relationship between the University of Bristol and the local arms industry remains comparable to how it was four hundred years ago. Extinction Rebellion Youth Bristol (XRYB) recently protested UoB’s continued promotion of Bristol’s three largest arms manufacturers, BAE, Rolls Royce and Airbus. Rolls Royce produce engines for the

Eurofighter Typhoon. This warplane was sold by the UK and Germany to Saudi Arabia and used to bomb civilians in Yemen. Sales of the plane to Saudi Arabia were halted in 2017 due to human rights violations, but the UK resumed these sales back in 2020 and Germany is presently preparing to resume sales in response to Israel’s war against Gaza. This is only one case of how university policy may be related to the ongoing legacy of colonialism, but I believe there may be more.

Obviously, student halls shouldn’t be named for the sake of glorifying the ill-gotten gains of colonialism. But colonialism isn’t really over and the University of Bristol isn’t yet separable from it. One thing the renaming of buildings allows for is the belief that the past is the past and the present affords a “fresh start”. Every symbol by which the university expresses itself is a product of the legacy of slavery. If the university were to take renaming seriously, it would have to start again from zero. This is called for, but, in order for the university to take a meaningful stance on

the political roles it played in the past, it would have to address the political roles it plays in the present. Anything less than a serious engagement with this reality will prove to be more empty crisis management. An ethically engaged university administration would have already renamed Goldney; the present one may not deserve to.

Want to read the other side of the argument? Find Alex Creighton's article here.

Feature Image Courtesy: University of Bristol

What do you think about renaming Goldney?