By William Sinclair-man, First year, Film and Television

A man flees from Paris to Poland after his divorce and attempts to get his life back together in the tragicomedy Three Colours: White (1994) which serves as the midpoint of the three colours trilogy by Kieslowski, this time focused on the theme of equality (égalité).

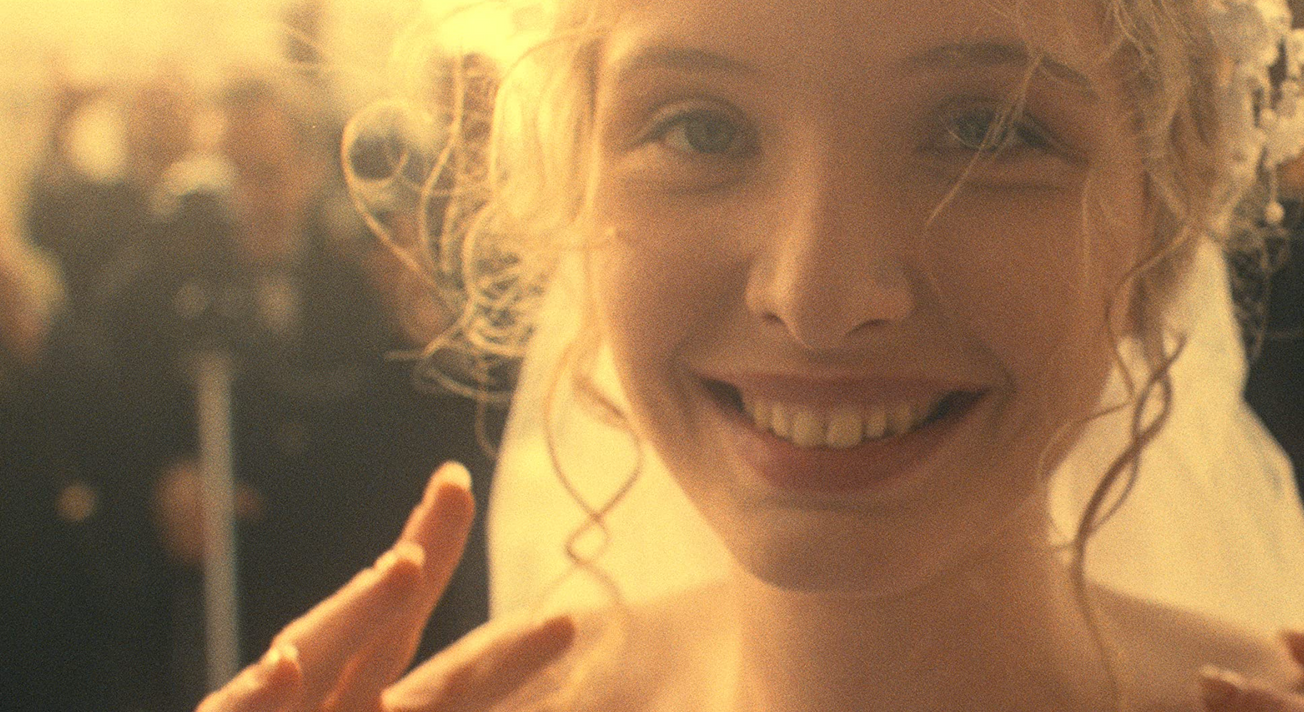

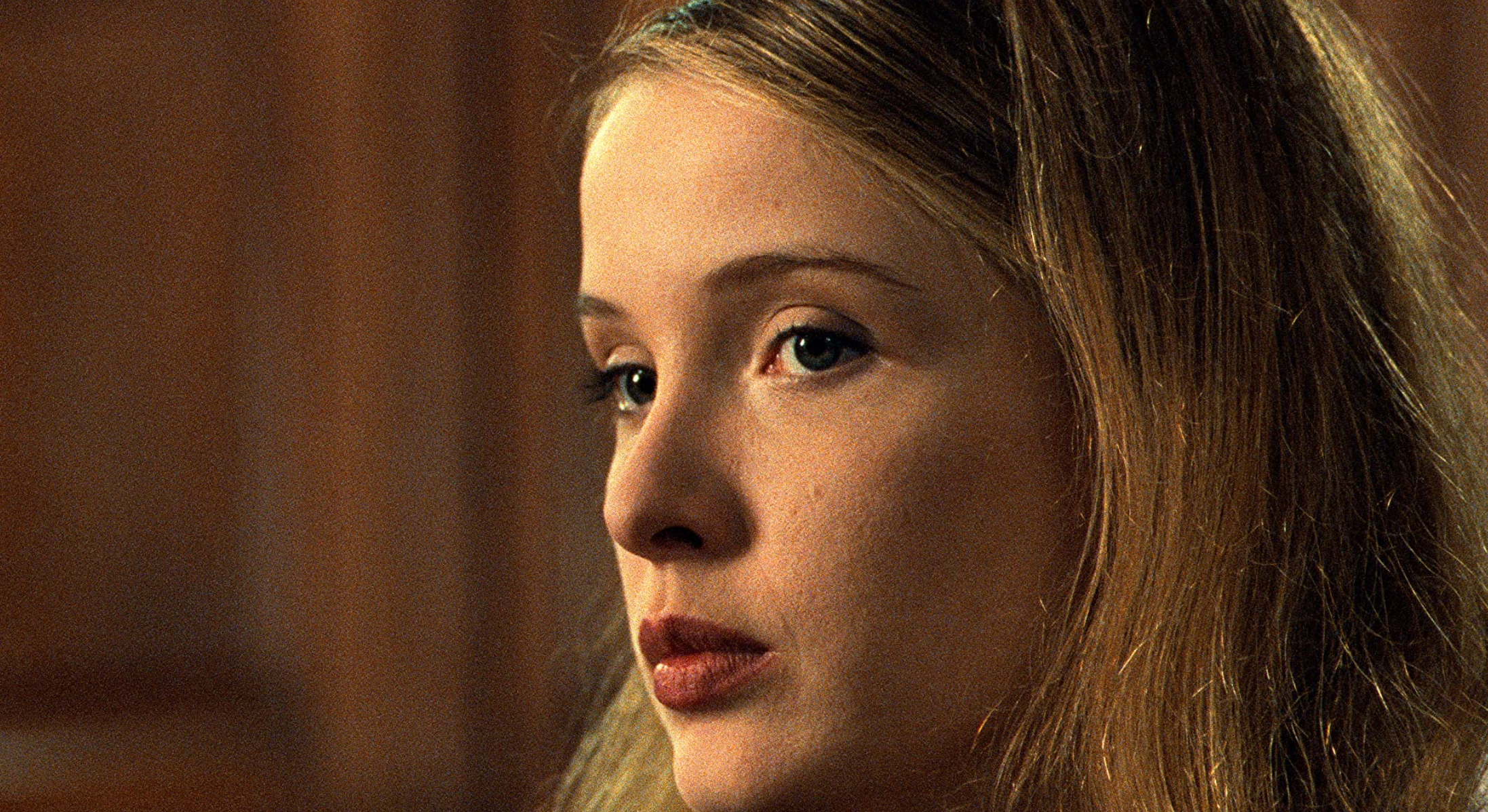

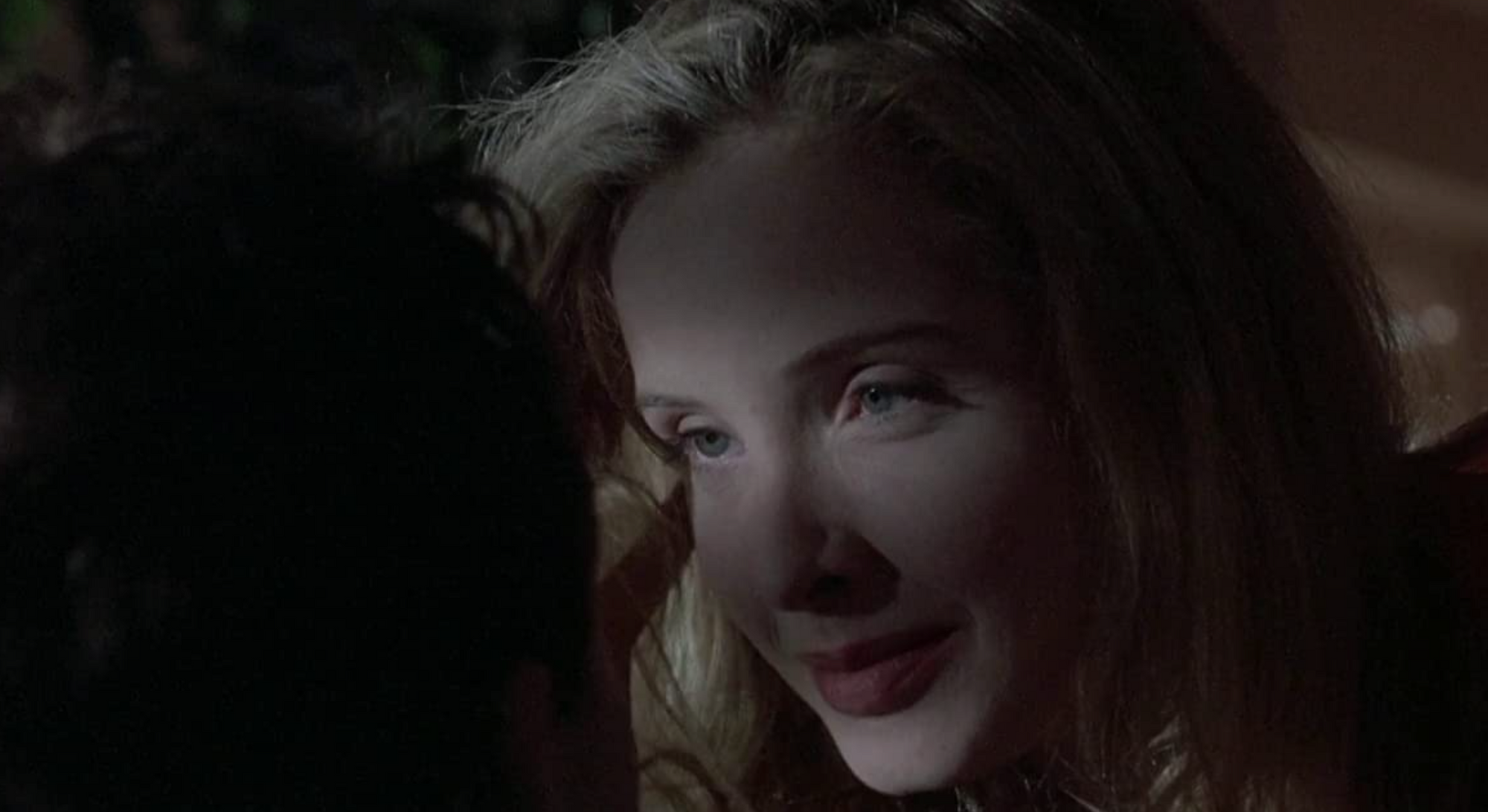

Polish hairdresser Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowksi) is divorced by his wife Dominique (Julie Delphy) and is left with nothing. While begging for change in the metro where he meets forms a connection with another Pole who agrees to smuggle him in his suitcase to Poland and offers Karol a job assisting with someone’s suicide. Poland recently transitioned from communism serves as a blank canvas for Karol to rebuild his life and - through a series of backstabs and shady deals - become a fully-fledged capitalist, ready to get even with his wife.

Visually the film is less impressive than its counterparts, though it’s difficult to give white the same visceral impact as the other colours of the French flag, blue and red but Kieslowski still manages to weave it throughout in interesting ways; Poland in the film is shown as a pure white expanse with its endless snowscapes and overcast skies, a place of possibility but one that is also cold and unforgiving to those less fortunate.

This association with white and coldness continues across the film with much of the plot revolves bureaucracy and business: the signing, acquisition, and loss of documents. Divorce papers, diplomas, deeds, and business orders. White pieces of paper apathetically shape so much of the characters’ lives. Despite this Karol carries a warmth that lets him stand against the frigidity of the world (for a time at least). It’s an engaging dichotomy that speaks to a lot of our struggle against nihilism and apathy in a world where we so often seem disposable.

Three Colours: White is less lyrical than the other films in the trilogy such as Blue with a greater focus on narrative. It is more naturalistic compared to the poetic formalism and abstract dreaminess of its siblings and while this may disappoint fans of Kieslowski this comparatively conventional approach (though still far removed from the traditional Hollywood approach to storytelling), combined with the films humour makes it Kieslowski’s most accessible work.

The film (fittingly given its title and colour palette) displays a rare degree of lightness compared to the rest of Kieslowski’s work, though the humour is still very much black. White derives much of its comedy from the misfortunes of its main character and cast with topics such as poverty, death, suicide, and loneliness at the forefront leaving the audience unsure whether to laugh or cry. Despite the bleak subject matter though, in the end, the film manages to produce a cautious sense of optimism: a faint glimmer that things might be okay.

A more conventional film than its predecessor and perhaps less memorable, Three Colours: White still manages to maintain many of the directors’ trademarks and tell an engaging, surprisingly funny (and just as often heartbreaking) story. For those looking for an entry point into European art-cinema though, this restraint makes white an excellent place to start.

Featured Image: IMDB

Have you seen this film trilogy?