By Tilly Long, Second Year, English

Famous for intimidating roles in gangster movies, Al Pacino’s most interesting choices are often overlooked, namely those centered around LGBT+ issues.

Al Pacino is best known for playing Italian mobsters, from Michael Corleone in The Godfather Trilogy (1972-1990) to Tony Montana in Scarface (1983).

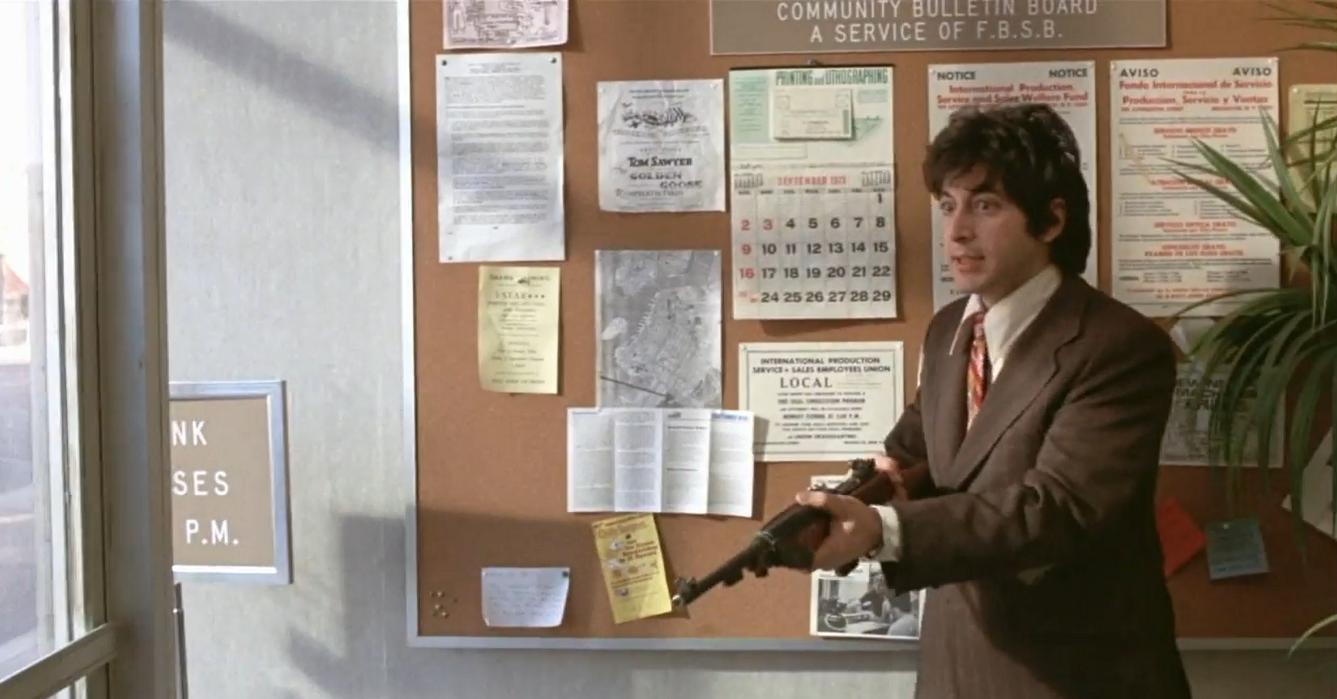

However, my favourite performance of his is Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Directed by one of cinema’s most influential voices, Sidney Lumet, the plot navigates Sonny’s frantic attempts to rescue his failed bank robbery.

Although it may not appear to be an LGBT+ film at first glance, there are clues. In Brooklyn, New York, on August 22, 1972, there was a fourteen-hour standoff between the police and the real Wojtowicz, whose motive was to steal enough money to pay for his lover’s sex change.

Pacino’s performance is memorable for a number of reasons. It took place in the same year The Godfather: Part 2 (1974) had gained him an Oscar nomination.

Pacino’s genius is to slowly un-menace his character, to the point where his own hostages start to care for him

At the time, it was very rare for a famous actor to play a homosexual. Paradoxically, as the film takes place almost entirely within the confines of his own crime scene, Sonny becomes an anti-establishment hero. We increasingly root for him.

In the film’s most iconic moment, he parades down the sidewalk, white flag in hand, shouting at hundreds of braying police officers, “Put your guns down! Attica, Attica!” referencing a notorious New York prison riot in 1971. Pacino’s genius is to slowly un-menace his character, to the point where his own hostages start to care for him. Aware of his emotionally fragile state and his marked distaste for putting them at risk, they begin to help him.

Sonny’s motives are eventually revealed in a live TV broadcast: ‘Police are questioning Leon Shermer, a 26-year-old admitted homosexual... they were married in an official ceremony… seven bridesmaids, all male and about seventy other guests, all members of the gay community, were present.’

Sonny’s most poignant moments occur when talking to Shermer (Chris Sarandon), who tells police, ‘I went to a psychiatrist who told me I was a woman trapped in a man’s body.’ She details that this triggered her depression and suicide attempt, whilst Sonny goes to extreme lengths to attain the money needed for a gender re-assignment surgery.

Despite his all too fleeting scenes, Chris Sarandon’s sensitive portrayal was Oscar nominated for this role. Lumet was fearful audiences would view the character in an insensitive way, and insisted the portrayal should not be caricature.

The film ultimately relies on the empathy of its audience; we grow to care for Sonny. During an emotional reading of his own will, he states: ‘to my darling wife Leon, whom I love more than any man has loved another man in all eternity.’

Lumet was fearful audiences would view the character in an insensitive way, and insisted the portrayal should not be caricature

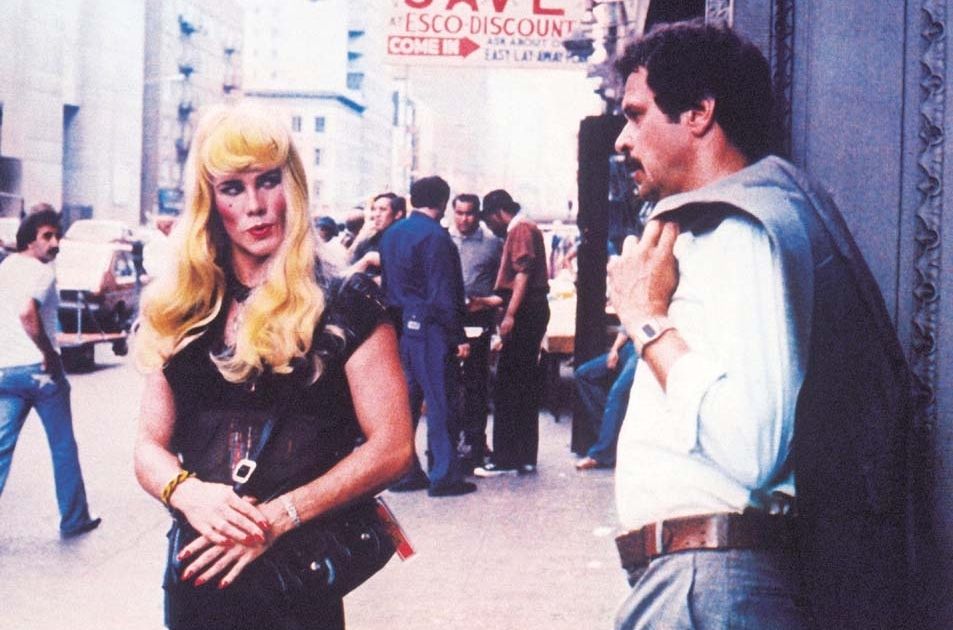

Pacino’s most controversial queer film is the erotic crime thriller, Cruising (1980). The plot follows detective Steve Burns (Al Pacino) learning to navigate the underground sadism and masochism scene of New York, as he goes undercover in search of a serial killer targeting gay men.

LGBT+ protests occurred even before the production began; their fear being that the small S&M subculture would be exaggerated to the detriment of the entire community.

Despite these controversies, the most interesting exploration of the film is one that is only alluded to: Steve struggling with his own sexual identity. Pacino plays the character with a particular innocence.

In a comic scene inside a scarf shop he is told, ‘A light blue hankie in your left pocket means you want a blow***. Right pocket means you give one.’ He embarrassedly replies: ‘I’m going to go home and think about it!’

The overt differences between his job in the police force and the gay clubs he attends evidently exacerbate

However, the overt differences between his job in the police force and the gay clubs he attends are evidently exacerbating, as he admits ‘what I’m doing is affecting [him].’ His girlfriend voices concern that he is no longer attracted to her: he mysteriously tells her, ‘There’s a lot about me you don’t know.’ Steve even contemplates giving up the job altogether, telling the police captain, ‘There’s stuff going down I don’t think I can deal with’, implying he is questioning his sexuality.

Whilst undercover, Steve befriends new neighbour Ted, who highlights the police as an inherent enemy of the LGBT+ community. Steve later directly challenges the abuse he witnesses at the hands of the police, asserting, ‘I didn’t come on this job to s**t-can some guy just because he’s gay.’

Cross-dressing hustlers in the film also prove the prevalence of police brutality; the opening of the film depicts two cops forcing them into their car and making them perform sex acts.

Whilst Cruising remains a potentially problematic film of its time in terms of LGBT+ representation, its analysis of internalised homophobia within Steve remains a curious case study, making it well worth a watch.

Featured: IMDb

How do you think Cruising has aged? Is it still worth a watch? Let us know.