By Noah Robinson, First Year Law

This five-decade retrospective is a startling and unflinching confrontation of the pervasive and systemic racism that marginalised communities face. In the wake of anti-Black state violence both in the US and internationally, it is a powerfully articulated response and a testament to Pindell’s expansive body of work, in A New Language currently at Spike Island.

The exhibition begins with Pindell’s early career in the 1970s, a style reminiscent of minimalism. However, it is nothing short of a wielded form of pointillism.

In Untitled (Talcum Power), the use of the chads (‘dots’) have strong implications of democracy and political participation. Whilst pre-dating the 2000 US presidential election, it implicitly recalls the infamous recount over ‘hanging chads’ to determine between Bush and Gore. This connection to voting is reinforced by the way that the chads become scattered and encased across the grid, becoming part of a visibly obsessive process to restrict and contain. Produced between 1973 and 1974, the works undoubtedly reflect contemporary measures to undermine Black Americans’ right to vote.

The neighbouring pieces emphasise this need to be seen, heard and represented. Parabia Test #3 takes letters from an inscription on a broken stone found by an enslaved person in the Brazilian state of Paraiba in the nineteenth century. Whilst unauthenticated, it provides potential evidence of contact between the Americas and the Mediterranean-based civilisation, Phoenician, long before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. It illustrates a need to reassess the way that global histories are told and reassessed. Blanketed in creams, ivories and peaches, it replicates Pindell’s own pressures from the art world “to whitewash everything in order to make it palatable”.

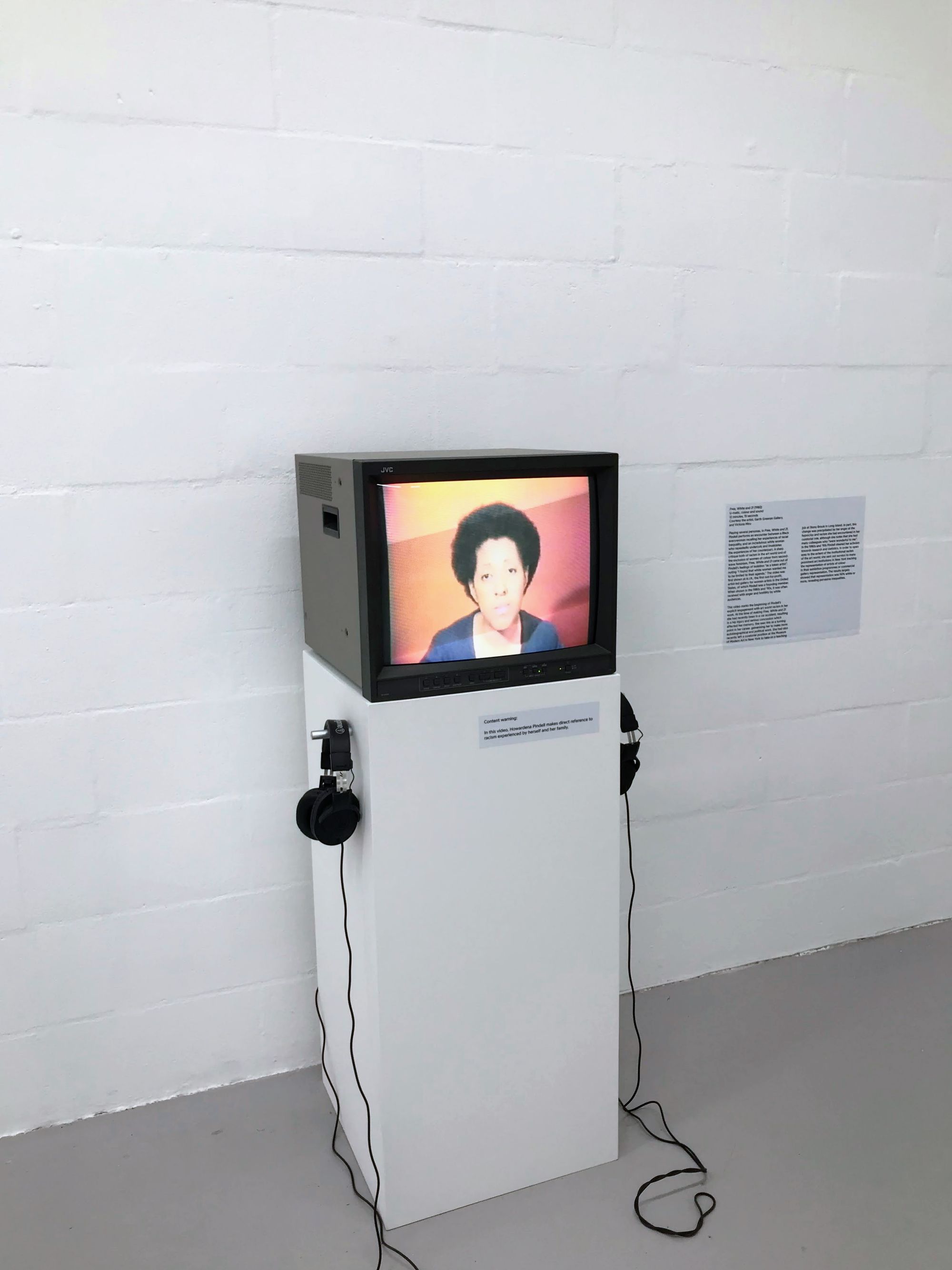

By the 1980s, Pindell’s work takes on an overtly political engagement, openly addressing her personal experiences of everyday racial inequality and micro-aggressions. Her film Free, White and 21 is sharp critique of the undercutting and invalidation of black experiences. It is a performance of an encounter between a Black “everywoman” and a white woman, in which Pindell conceals and reveals materials from her head and face as a metaphor for social constructs of race and colour. This desire to silence black voices, as Pindell recalls, is an extension of the legacy of slavery. It is also a clear confrontation of how unrepresented black artists remain; in the art world, as recent as 2022, they only make up around 2% of all auction sales.

Pindell’s later work moves forward, both formally and thematically away from abstraction. Building on the seminal title of the exhibition, the work creates a ‘new language’, combining text, photo, video and canvas. The paired War: Agent Orange (Vietnam #1) and War: Starvation (Sudan #1) begins Pindell’s exploration of the way that the media frames blackness, as well as the way that black communities can reclaim such tools to document their own experiences in a form of citizen journalism. Against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement, it illustrates the way that social media can connect us and be used as a means to resist the distortion and silencing of marginalised voices.

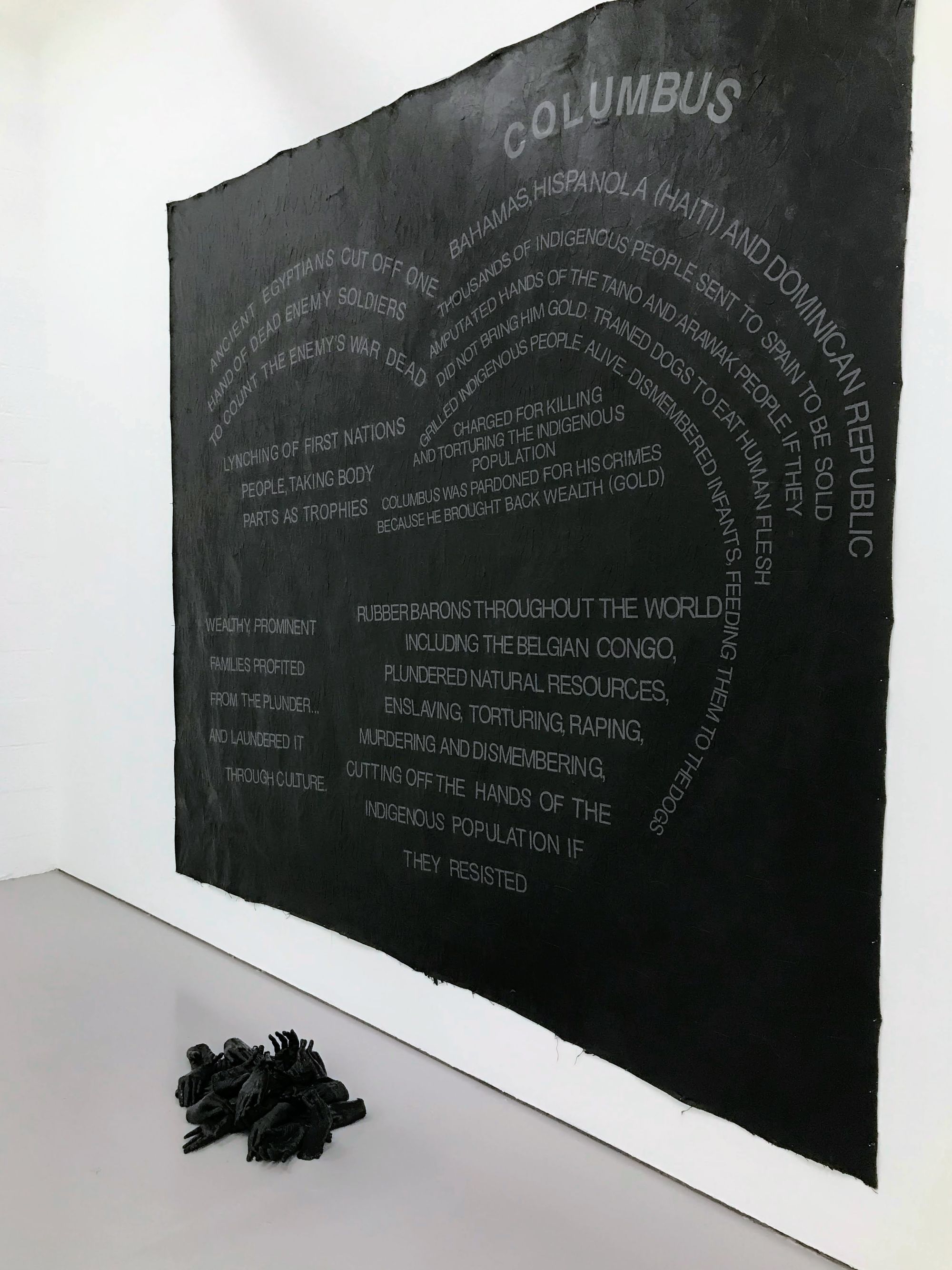

In this examination of the past and present, Pindell explores the ways that black bodies carry the generationally traumatic legacy of imperialism and slavery. Columbus collages black hands and text onto canvas, describing the atrocities committed in the name of wealth and empire. These horrific acts become twisted in a raw encounter between then and now, illustrating how this lure of profit, wealth and privilege has become embedded in structures and institutions, built on oppression and violence.

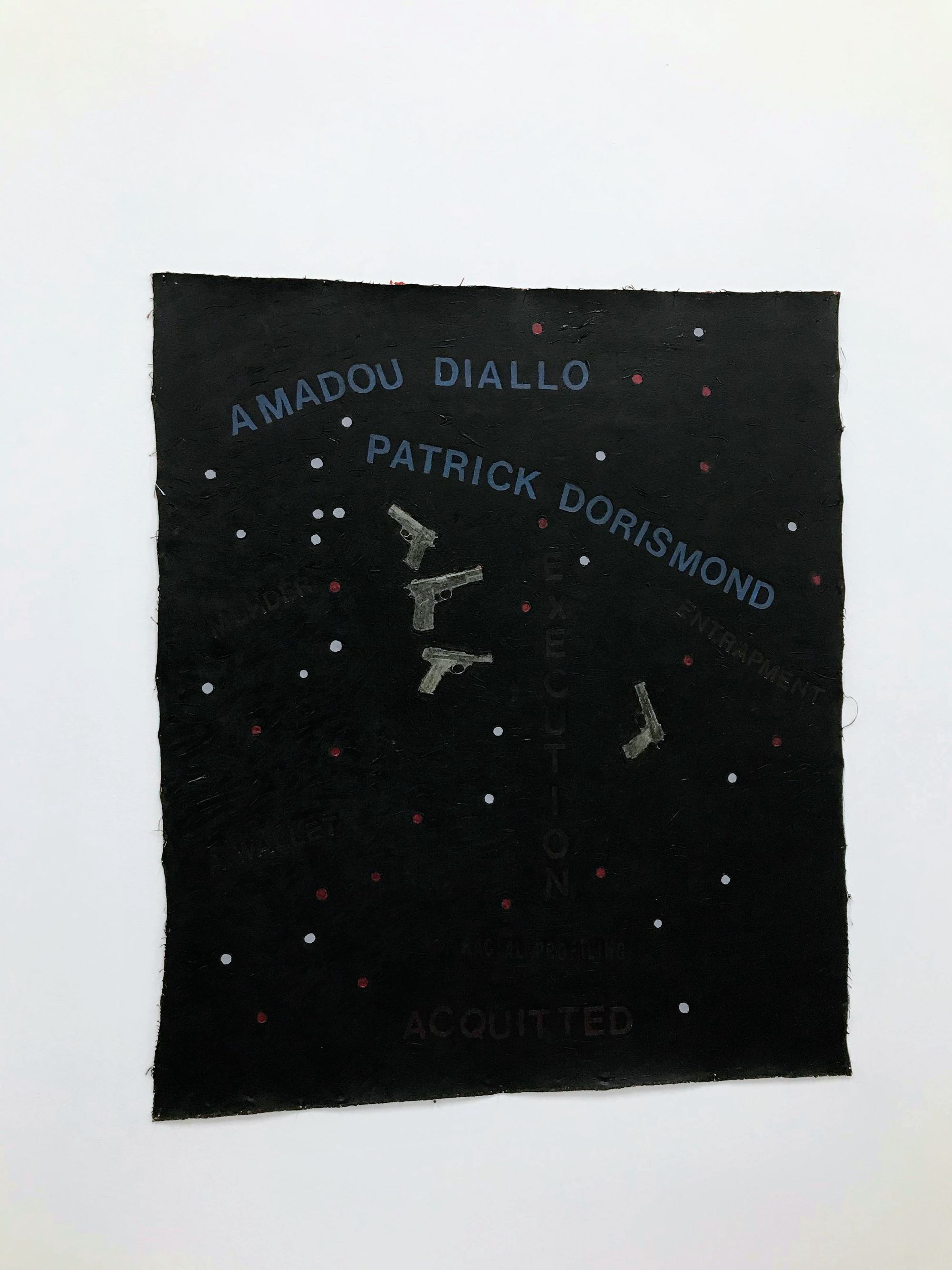

This is most apparent in Diallo. The title refers to the fatal shooting of innocent and unarmed 23-year-old Amadou Diollo by four NYPD officers in 1999. It is a story that is easily and sadly recognisable. The red and white dots on the canvas indicate the forty-one shots fired, against a seething black darkness.

Under this banner of ‘protect and serve’, Pindell’s contemporary work confronts the hypocrisy and systematic racism in so many of our institutions. Separate but Equal Genocide: AIDS is a present reminder of the disparities in US healthcare between white and black patients: an injury of inequality. It remains an illustration of the disproportionate impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on Black Americans due to the intersection of ‘urban renewal programmes’, social oppression and racial barriers to accessing healthcare in the 1980s and 1990s.

Pindell’s most recent film Rope/Fire/Water features black and white archival images of lynched bodies interspersed with long periods of black screen. The subtitled narration describes historical and contemporary cases of racialised violence, underlined by a commanding tick of a metronome. It is a counter to tallies and numbers of the hard-hitting data: a reminder of the true human cost and individual lives lost.

A New Language is a sobering reminder that violence against Black people is not only a historical truth, but an undeniable ongoing crisis.

The exhibition runs at Spike Island until 21 May.

Featured Image: Courtesy of Noah Robinson

What was your favourite piece from Howardena Pindell's exhibition?