By Milly Randall, First Year, English

In this sparkling love story, director and co-writer Wanuri Kahiu seduces us into the vibrant world of suburban Kenya, where the initial connection of two adolescents Ziki (Mugatsia) and Kena (Munyiva) blossoms into love and friendship.

Throughout Rafiki, both lead actors, Samantha Mugatsia and Sheila Munyiva, are electric and captivating in their portrayal of the first flutters of romance. Beginning with tentative looks and even the predictable mood of conflict between the two, Mugatsia and Munyiva’s performances are vulnerable, but most overwhelmingly: persuasive. With the opening credits featuring buildings of pastel pink and blue, and colourful and ugly fruits chopped on the sides of the street, we are quickly submerged into Kahiu’s world.

YouTube / IndieWire

This electricity is of course heightened by the trope of ‘forbidden love’. Not only is homophobia still at a height in Kenya, with homosexuality still a criminal offence, but there is the added aspect of class difference. Ziki’s father, Okemi, is running against Kena’s in the upcoming local elections, and this political feud only adds more colour to this multifaceted narrative, which addresses many issues on many levels.

The complexity of Rafiki’s plot undoubtedly enriches the composite characters: the audacious but obedient Ziki, who seeks more overt terms of expressing her love, and the calm, confident, but understandably cautious Kena. These characters are utterly convincing, and fully portray the heat of first love with all of its gaping silences and stilted conversations.

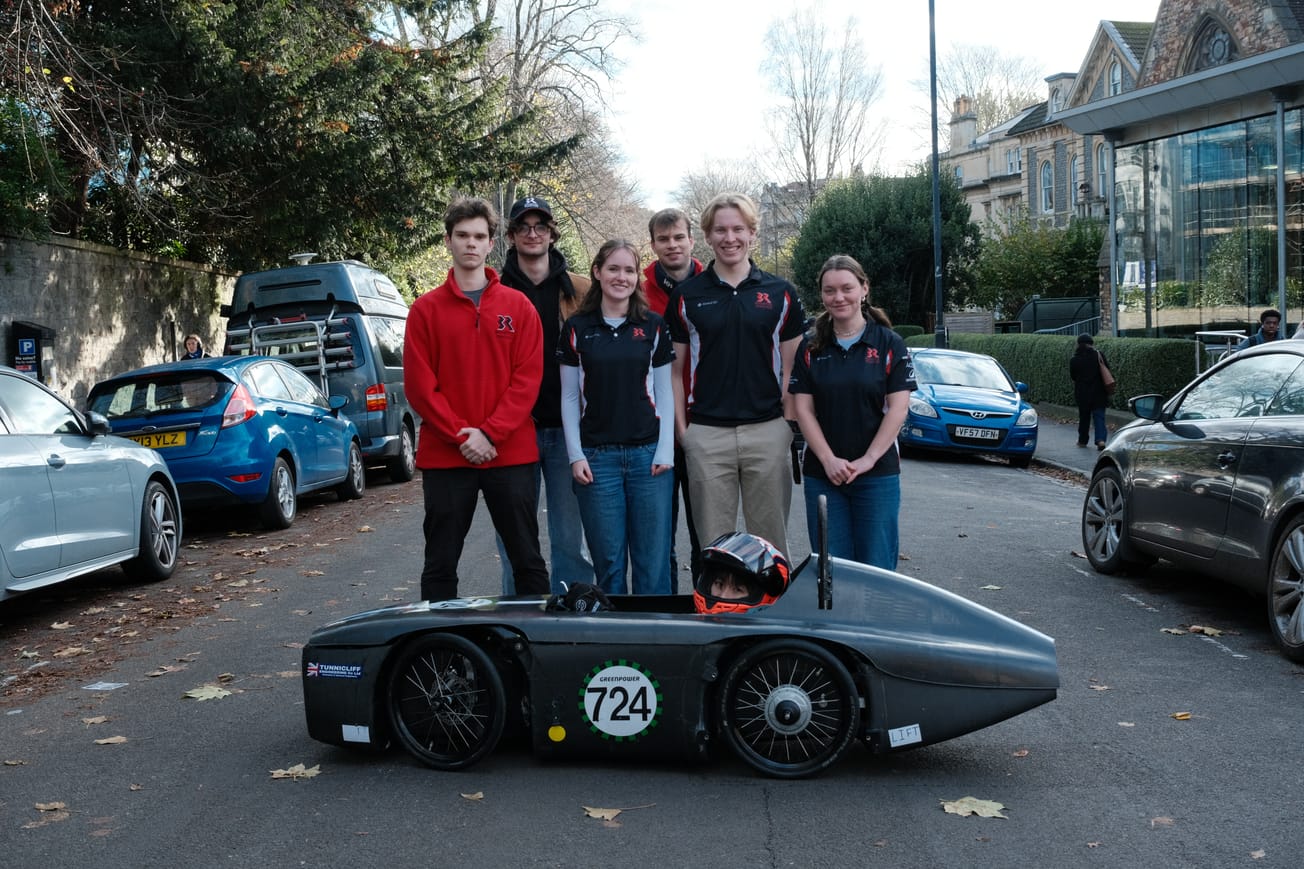

Photo courtesy of Watershed

Cinematographer, Christopher Wessels, intensifies these moments of vulnerability, with extended close ups of both Ziki and Kena. Dripping in light leaks and twitches of afternoon sun, Wessels manages to evoke a sense of nostalgia through, quite literally, rose tinted glasses. The images naturally cause the audience to reinstate their own youthful experiences, creating a sense of empathy and personal connection to these characters. This is made more emotive by the beautiful soundtrack to the film, with major key dance numbers, and notably the slow whispery melody of ‘Ignited’ by Mumbi Kasumba.

Overall, this film is hopeful. No one is ultimately punished, no one dies horrifically, like so often happens historically in queer romances. As was discussed in the panel at Watershed after the opening night screening, there is tolerance to LGBT+ relationships in Kenyan society, but Rafiki challenges the limitations to this tolerance. The reason this film was banned in Kenya was not purely due to the story, but for the lack of remorse that Kena showed for her ‘actions’.

#RafikiMovie convo kicking off @wshed with this great panel 😍 pic.twitter.com/z32tOzQ3r3

— Tara Judah (@midnightmovies) April 19, 2019

There has been criticism that the narrative here follows too many cliches of a love story, but I think it’s the adhesion to these classic romantic tropes which makes the film so powerful. It lends a purity to the friendship (rafiki meaning ‘friend’ in Swahili), which combats the tragic moments of the young girls being exorcised of their apparent demons publicly in church, or brutally attacked, verbally and physically.

Kahiu has created a heart-warming love story in Rafiki, and if Kenya moves towards decriminalising sexuality and public consciousness shifts, I’m sure the film will be embraced as a classic.

Rafiki is showing at Watershed until 25 April.

Featured Image courtesy of Watershed

Will Rafiki help a social movement in Kenya for more tolerant legislation?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter