By Helen Barber, Second Year, Biochemistry

Antibiotic resistance is perhaps the biggest crisis modern medical professionals face. Globally, it kills 700,000 people a year. This is primarily due to the overuse of antibiotics where they are not needed. Unless something is done to change the tide, this uncontrolled spread of antibiotic resistance will continue, causing more deaths. However, a new study led by the University of Bristol may offer a way to decrease needless antibiotic use.

Antibiotics are one of the hallmarks of modern medicine. The discovery of the first antibiotic penicillin, by Alexander Fleming in 1928, marked the beginning of the ‘antibiotic era’. Since then, the number of antibiotics available to us has greatly increased, and in the developed world, severe bacterial infections are no longer the lethal threat they once were. Antibiotic resistance, however, is helping to return these diseases back to their original hazardous state.

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria evolve mechanisms to protect themselves against the antibiotic drugs administered to fight against them. Due to the ability of bacteria to rapidly replicate, their evolution happens on a much shorter scale than that of humans, and so new mutations can quickly occur. Some of these mutations may give rise to resistance and are permanently integrated in their DNA. When antibiotics are then used on an infection, only those few that have antibiotic resistance can survive and go on to multiply, producing more antibiotic resistant bacteria in the population.

Now antibiotic resistant, we are unable to use that class of antibiotics to treat the bacterial infection. Instead we must switch to a different, potentially less effective or more harmful, antibiotic class. However, in some cases, even this isn’t an option. The rise of multi-drug resistant bacteria, which are bacteria resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics, means our choices of drug treatment become severely limited. There have already been cases of bacteria resistant to the majority of available antibiotics, causing life-threatening infections.

There have already been cases of bacteria resistant to the majority of available antibiotics

There are many reasons why antibiotic resistance has been able to arise and grow in number of cases. One is the overuse of antibiotics; many being prescribed even when there is no benefit to the patient. This is dangerous as the more antibiotics are used, the more opportunities bacteria have to develop resistance.

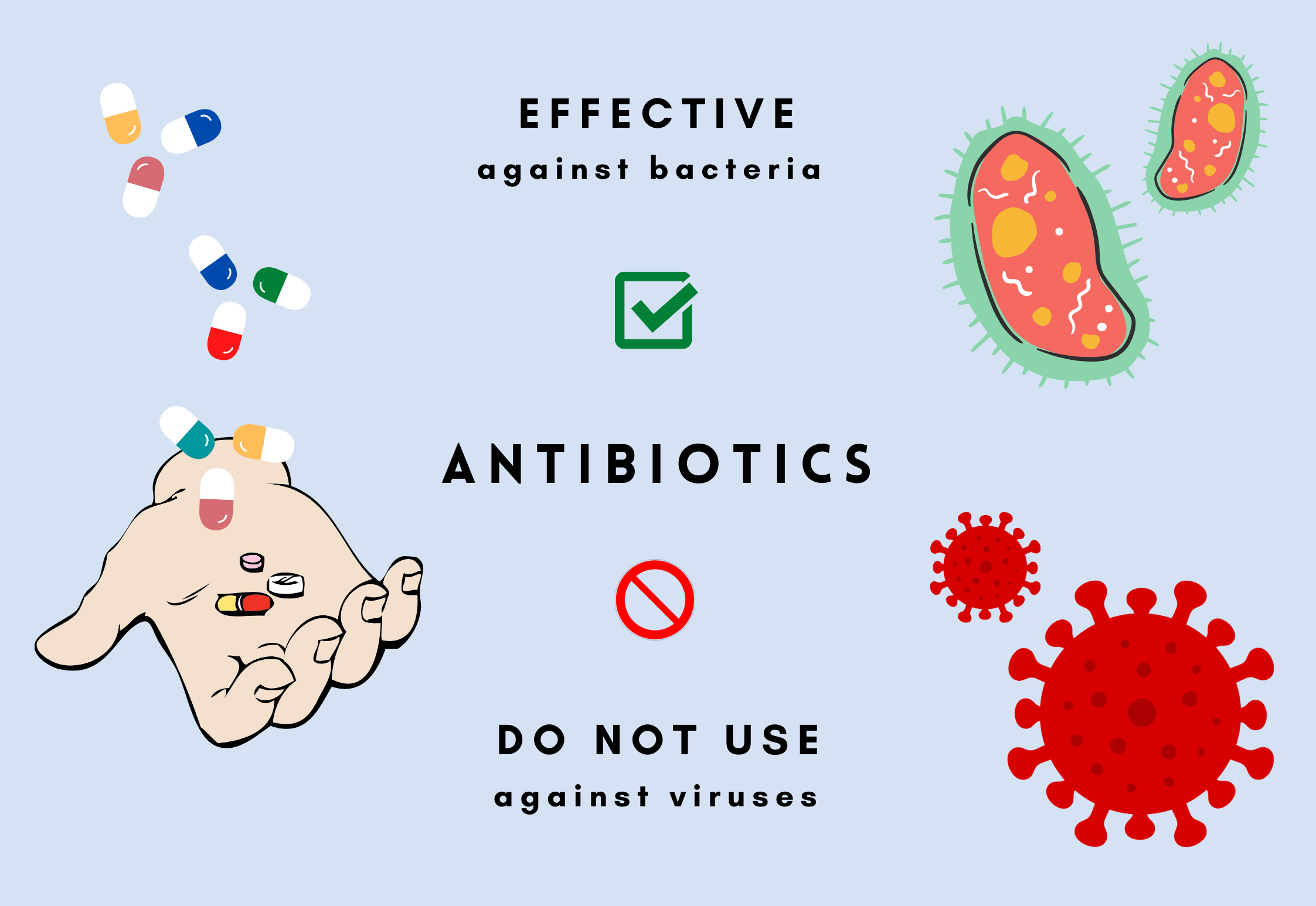

One way to decrease the spread of antibiotic resistance is to reduce the number of antibiotics prescribed. While antibiotics are effectively used to treat a great number of otherwise lethal bacterial infections, many antibiotics are prescribed needlessly. Antibiotics have little effect on viral infections, and yet often they are prescribed by GPs as the symptoms are similar to those of bacterial infections. Therefore, doctors need a method to quickly identify the cause of a patient’s symptoms, in order to make correct prescriptions.

Learn how @BioFireDX can help you strengthen your #clinic with point-of-care infectious disease testing. #CLIAwaived #PointOfCare #SyndromicTesting https://t.co/wS57chKqLu pic.twitter.com/xU89QYQbih

— BioFire Diagnostics (@BioFireDX) March 4, 2021

The solution may come in the form of the BioFire® Filmarray® v1.7 (bioMérieux) microbiological point-of-care test. This swab test can detect the presence of 17 different respiratory viruses and three atypical respiratory bacteria in the nose and the back of the throat. Doctors are able to use this test and receive results in 65 minutes, allowing them to better diagnosis and treat infection.

While similar point-of-care tests are already in use in the UK, they are currently only used in hospitals. A study, led by the University of Bristol’s Centre for Academic Primary Care (CAPC), was conducted using the BioFire® test to see if such tests would be useful in GPs surgeries.

The study took place in four south-west GP practices over six weeks. Of those given the test, 35 per cent of patients who would have otherwise been likely prescribed antibiotics were found to have no virus or bacteria, whilst 25 per cent of potential antibiotic patients were found to have a viral infection.

This test does not test for the most common respiratory infection-causing bacteria

However, this test does not test for the most common respiratory infection-causing bacteria, as these can also live harmlessly in the nose and throat without causing an infection. Therefore, it is possible that those patients found with no bacteria or virus may still have a common bacterial infection, which antibiotics must be prescribed for.

Indeed, GPs changed their diagnosis in one out of five cases where testing was done and said they felt more certain about their diagnosis afterwards. Alastair Hay, Professor of Primary Care at the CAPC and the leader of the study, stated: ‘The results show the potential of these tests to improve diagnostic certainty and reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing’.

Bristol University’s micro-bots could change the face of medicine

Treatment for addiction: How are patients coping with the pandemic?

This is a vital first step in the fight against antibiotic resistance. Professor Hay continued to explain that ‘clinical trials are now needed to see if these point-of-care tests can safely and cost-effectively reduce antibiotic prescribing.’

It is hoped that these point-of-care test kits will be shown to be effective and become more commonly used in GP diagnosis. This would both increase the reliable of GP diagnosis and help decrease the spread of antibiotic resistance, something that is sorely needed in our fight against it.

Featured Image: Epigram / Julia Riopelle (using Canva)

Have you been prescribed antibiotics more often than you would expect?