By Barney Johnson, Third Year, Film and TV

It can be argued that there is no genre in film that is more impactful, more iconic, and more polarising than horror. It may be more effective at achieving its desired effect on its audience than any other genre, but consequently could perhaps be ascribed as the most difficult type of film to get right.

Anyone who likes cinema will have an opinion on horror, whether it be for or against; but the fact remains that it is a genre that has remained and outlived many other film types, such as the Western, the Slapstick or the Film Noir, whose legacies, for the most part, are cemented exclusively in the past.

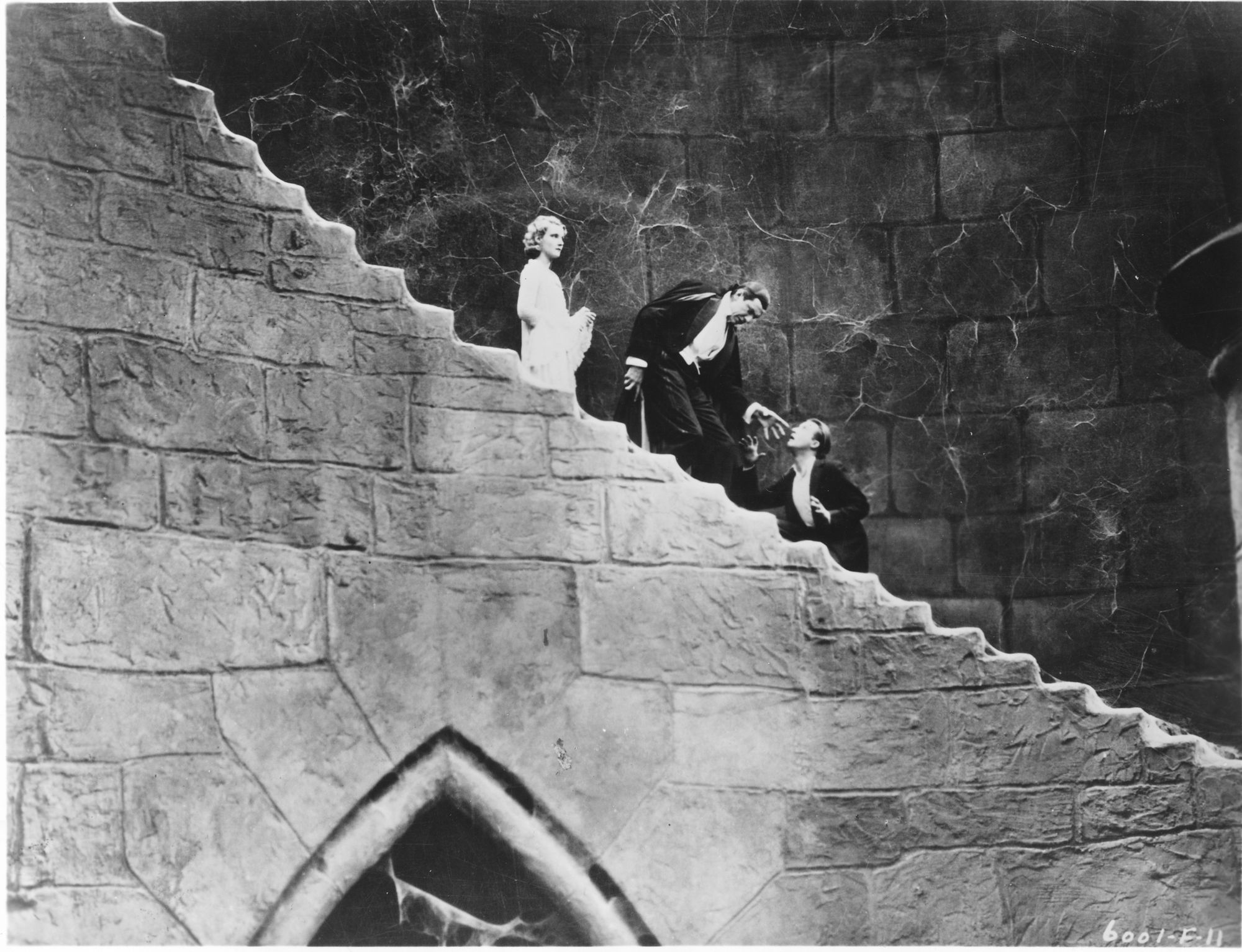

Though its subgenres may reach periods of burnout over time, horror as a whole remains a constant fixture of the cinematic catalogue, with its roots standing as far back as a century ago with early entries such as Nosferatu (1922), The Man Who Laughs (1928) and Dracula (1931).

Perhaps the catalyst for its commercial springboard into popular commonplace Western cinema was the emergence of the slasher film in the late-1970s to mid-1980s, which generally consisted of a young protagonist being hunted down by a monster with seemingly insurmountable power.

While Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) is often attributed with being the progenitor of slasher films, the two milestone releases that really validated horror as a financial hit were Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), whose successes launched a myriad of frightful flicks for the next decade or so with a proven narrative formula and setting replicated over and over.

As such, subsequent films unravelled from their popularity, alongside other similar film franchises such as Friday the 13th (1980-2009), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-2010) and Child’s Play (1988- ).

The zeitgeist lens that horror finds itself looking through in the 21stcentury is now that of the supernatural, especially that of the possessed, the haunted, the unholy.

No doubt much of what constitutes modern horror and the slew of paranormal releases that are churned out on a yearly basis can be attributed to Friedkin’s seminal The Exorcist (1973), which remains to this day one of the most beloved and memorable horror films of all time to many horror buffs, primarily for its disturbing imagery and brazen commitment to repulsing its viewers.

Of course, the ultimate question pertaining to this most unique and striking method of visual storytelling is: Why do we enjoy horror films? As well as how has it managed to endure for so long, as a genre, when others have simply faded into the sands of time?

Perhaps the first step in trying to obtain an answer to that would be to cement an understanding of what “good” horror is. It must be emphasised at this point that there is no definitive description of what constitutes “good” or effective horror.

This is dependent on the individual viewer’s own plethora of phobias and anxieties, and whether a specific monster, situation or environment strikes fear into their hearts.

However, a common rule of thumb for writing captivating horror is the idea of taking the comfortable and the familiar and transforming it into the uncomfortable and the unfamiliar.

Often, I find that my own reactions to horror films are at their most extreme when the respective narratives feign control and security to both its characters and to me as a spectator in its opening act, convincing me that I understand the situation only to then have my sense of reality and safety challenged.

Some iconic horror films that come to mind that utilise this approach are Alien (1979), Audition (1999) and The Thing (1982), all of which introduce the true extent of their horrific elements as the narratives’ events escalate.

It is this unshakeable state of paranoia and an inability to escape the dread of an idea that inspires the most fear in me, and it is an irrefutable thread that binds horror across its entire ancestry. Because of this characteristic, many audiences find films that were not intended primarily to be horror films terrify them more than works whose intention was to do just that, as that false sense of understanding the situation is amplified further.

For example, many viewers of my age will have childhood memories of films or programmes whose uncanny visuals and unexpectedly dark themes permeate the mind for years after their first watches, such as Coraline (2009), Monster House (2006) or the modern era of Doctor Who (2005-). All of this jarred me upon first viewings with how surprisingly they delved into the horror genre for supposedly more innocent narratives.

Thus, the Other Mother from Coraline and the Weeping Angels from Doctor Who remain to this day a far more traumatising visual than that of Michael Myers or Freddy Krueger, simply because the former pair of monsters appear in more light-hearted narratives and yet belong in horror films all the same.

Another film that comes to mind that is terrifying despite having no such marketing to be a horror film is Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), which on the external poses purely as a Sci-Fi survival film, yet most viewers would agree that from the beginning to end it is relentlessly suffocating and anxiety-inducing, to the point of genuine visceral unease.

It must be highlighted, therefore, that there is an inherent desire within many people to be scared, unnerved and disgusted, otherwise horror films would not have an unwavering audience for 100 years.

Perhaps it would be accurate to say that the appeal of the horror genre comes from enduring the suffering of the protagonist almost as if it were oneself suffering their terror. We bear witness to their horrific journeys, with their fear and ours not so far apart, thus making the relief brought about by a resolution – a most impactful and valid catharsis.

That rush of adrenaline, that reminder of one’s vitality, the very fear that comes simply from being alive and having to endure the cruelty and agony of our world, is perhaps a feeling that is made a little easier to cope with thanks to the escapism provided by the world of horror cinema.

As for my own favourites, I would recommend the following films for both horror buffs and novices to the genre alike:

- It Follows (2014) – for its masterful handling of paranoia through a familiar but ever-daunting premise and simple but effective cinematography.

- The Descent (2005) – for its impressive ability to constantly escalate the dread of an already claustrophobic and bleak scenario.

- The Conjuring (2013) – for quite simply a sequence in a basement that has terrified me since the age of 10, and the mere thought of it brings me goosebumps every time without fail.

- The Birds (1963) – for taking a seemingly absurd and mundane idea and turning it into a genuinely tense and phobia-generating experience.

- Misery (1990) – for taking the appeal of celebrity status and flipping it into one of the most harrowing and toe-curling prospects imaginable.

Featured Image: Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., courtesy of IMDB

With Halloween approaching, which horror films will you watch this October?