By Carissa Wong, PhD Cancer Immunology

Nancy Grace Roman was a pioneer of both women in science and the world-renowned Hubble telescope. In 1959 she became NASA’s first chief in astronomy, and the first female executive at the American Space Agency. Nancy was an inspirational advocate for women in science throughout her life.

Nancy’s curiosity for the cosmos began at a young age and lasted until the day she passed, aged 93 on December 25th last year. Her mother would show her the stars and auroras and her dad would answer her scientific questions. “It was probably my parents who inspired me most” she said in a NASA interview. At 11 years old whilst living in Nevada, she organised a summer astronomy club with her school friends to study the constellations. Space captivated her and she would devour library books on astronomy. However, it was not easy for Nancy to follow her passion.

Throughout her life, Nancy saw beyond beliefs of society that “women were not supposed to be scientists”. At secondary school she was asked by a counsellor “What lady would take mathematics instead of Latin?”. Undeterred by this, she took algebra classes and went on to study Astronomy at university. Here she was told that she “might make it”, while being taught by professors who thought women were best suited for marriage, not education.

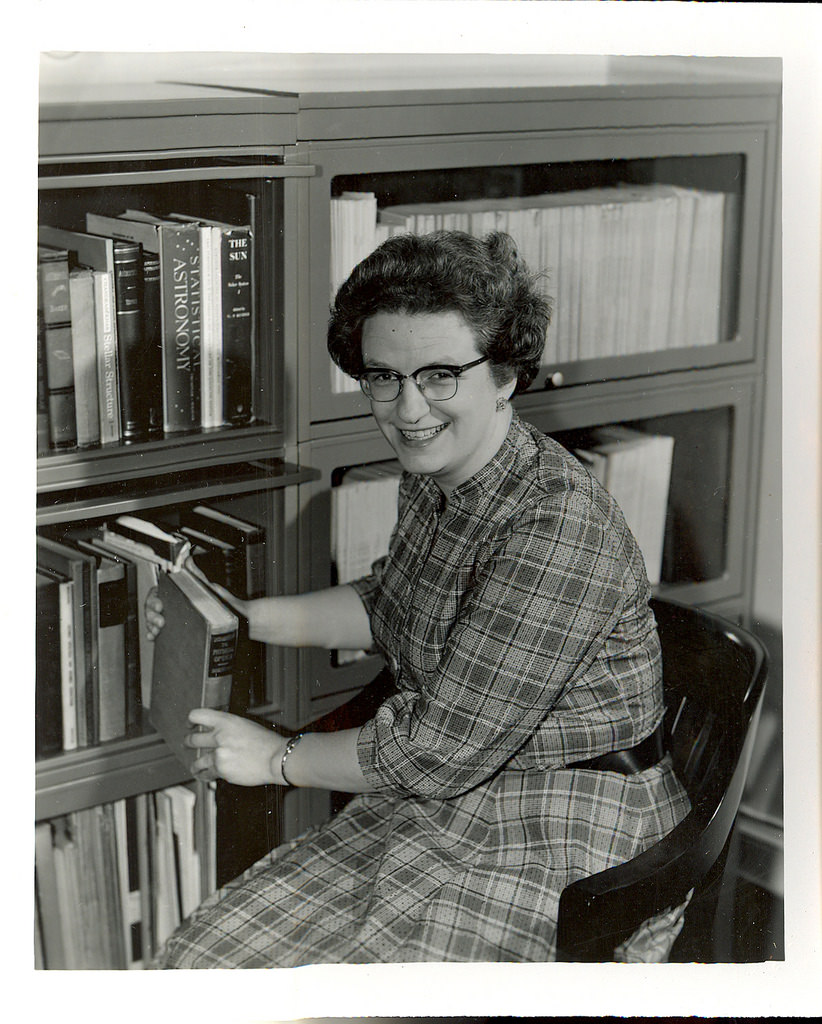

Dr Nancy Roman, NASA Hubble Space Telescope/ Flickr

Years down the line, Nancy had earned a PhD in astronomy, and went on to take post-doctoral and assistant professor positions studying stars to shed light on the Milky Way’s evolution. Her novel research showed that stars comprising of more heavy elements and following a more circular orbit are older than stars which orbit more randomly and contain few heavy elements.

In 1959, whilst attending a lecture about the moon, Nancy was told that NASA was looking for a Chief in Astronomy. She successfully won the job and it was over the next 20 years that she played a key role in enabling the construction and launch of the Hubble telescope.

It was at NASA that Nancy finally felt treated as equal to men. Nancy was able to convince politicians that NASA and the European Space Agency should cooperate to bring the Hubble to life; she successfully lobbied for the funding required to support the project. She worked as an interpreter between scientists and engineers, forging the foundations of a team that would soon revolutionise space exploration.

First envisioned in 1946 by Lyman Spitzer, the Hubble telescope was named after Edwin Hubble, an astronomer who transformed the field when he discovered galaxies outside the Milky Way and provided evidence that the furthest galaxies from Earth move faster away from our planet. It was Nancy’s perseverance and dedication in the face of failure and scepticism that enabled the idea of a space telescope to be realised in 1990.

Owing to its location beyond the distorting effects of our atmosphere, the Hubble lets us peer into the cosmos with incredible clarity. It can observe infrared and ultraviolet light which cannot be easily detected by ground telescopes, providing useful information on areas such as galaxy evolution. Since its launch, the Hubble has made over one million observations of stars, galaxies and planets. Data acquired by the Hubble has contributed to over 15,000 published scientific papers; its contribution to astrophysics makes it one of the most valuable scientific instruments ever built.

Nancy is a shining example that gender is irrelevant when it comes to scientific competency; she encouraged women to take up science throughout her life, giving talks and mentoring young female scientists new to NASA: “One of the reasons I like working with schools is to try to convince women that they can be scientists and that science can be fun.” Today, NASA is made up of over 30% female employees, and in 2013 the first NASA astronaut class containing 50% female candidates was recruited.

According to a WISE (women into science and engineering) study, women made up 24% of core STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) employees and held 15% of STEM management roles in the UK as of 2017. In the same year, 41%, 39%, 15% and 14% of physics, mathematics, computer science and engineering graduates, respectively, were women. In 2012, women formed just 15% of core STEM employees and less than 10% of STEM management roles in the UK, showing that the trend is in the right direction; more women in STEM means more role models for the young women of today.

Featured Image:NASA Goddard Space Flight Center/ Flickr

Do you have any scientific heroes? Let us know!