By Finnuala Brett, Travel Editor

The Croft Magazine // When the world of travel feels more limitless than ever, the places from home are sometimes the ones most worth exploring.

One day, the house my mother grew up in will no longer exist. In perhaps a decade, or less if the Irish winters are bad, the vines in the smallest bedroom will have bulged and cracked that stone wall into shattered pieces, and rain will fall through onto the floorboards and grow into a puddle spreading damp rot from door to window. The crack in the dining room window will widen, and on one cold night shatter and collapse, exhausted. The living room, with the bay windows where you can see all the way down to the lake as it lies silver under the sky, this might be the last room left. And though it is inevitable, it hurts to think that this part of my past will dissolve into a shell of itself that smells of Irish bog-lands and woodworm.

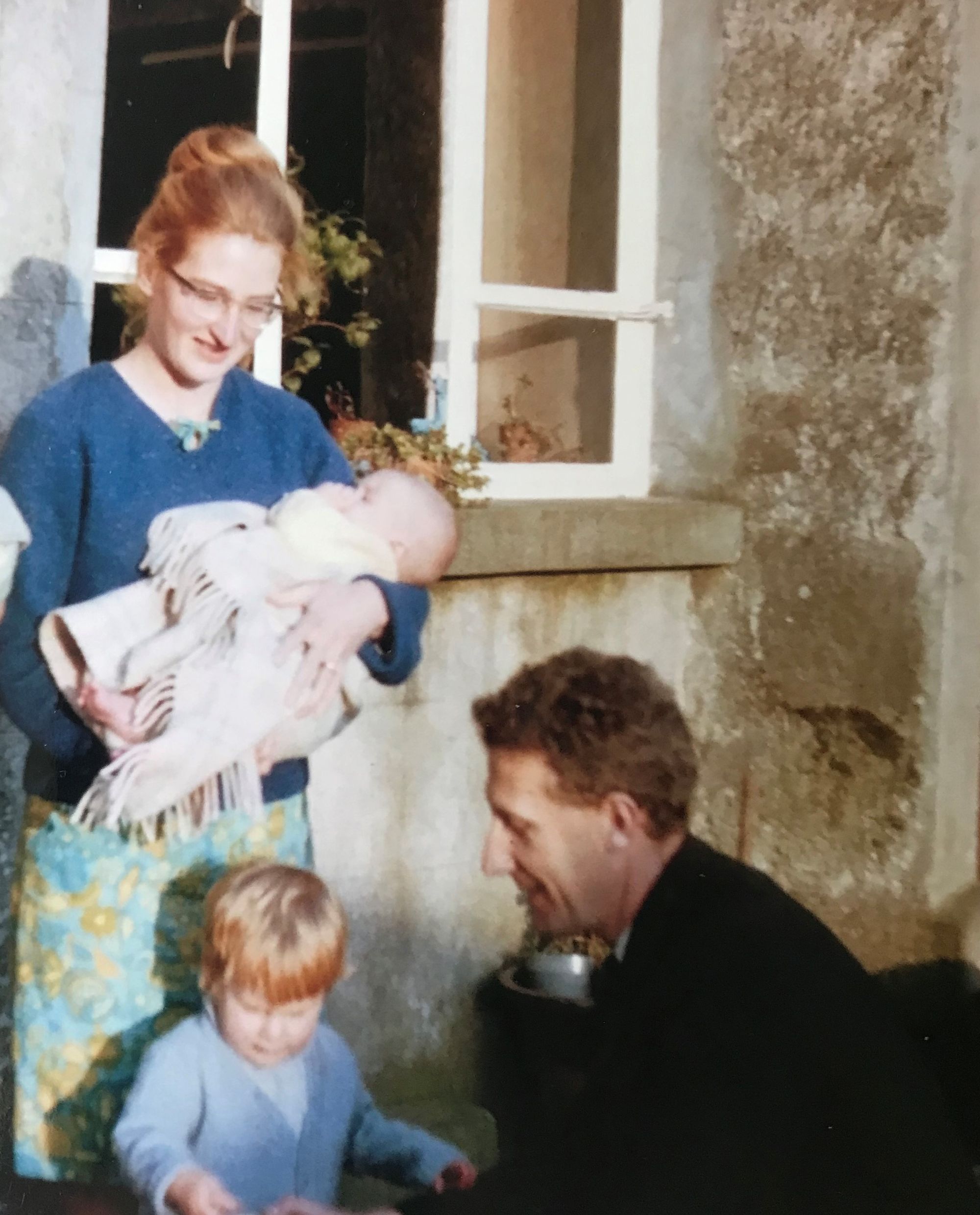

My first taste of Ireland was that of salt water. I was not yet a month old, in the arms of my tired mother, come to dangle my tiny feet in the Atlantic at the beaches along this coast: Murvagh, Rossnowlagh, Bundoran. These names sound as if they have been plucked from the pages of a child’s fairytale. Tullen Strand, a miles-long stretch of dimpled sand, clean and bright beneath the steely sky; Ardara, its sand dunes distorted by the storms every year, the caves this time submerged and next time empty and dry. Waterfalls tumble down steep mossy hills, and meets the sea as it leaps up in great sprays of white.

This part of the world is very beautiful, even through the rain it suffers every day of the year, and the damp that gets to the bones. There are few footpaths, and few houses – the little squat white walls buried into dimpled ground, red window frames and low eaves – and the roads twist between moraines left by ancient glaciers. Lakes collect in indentations in the land, where the clay is too thick or the bog too saturated for the rain to drain. When the sun occasionally emerges, the moorlands are transformed into a patchwork of mirrors. The firs grow thick in the forests, and scotch pines down near the coast are bent and blistered by salt winds.

My grandmother paints it all. She loves the colours, she says, and takes her little jar of turpentine and bag of oils out in the car, to drive along until she finds a new view. Every corner of road and field is memorialised in her canvases, stacked on the landing in the house. Some are unfinished, some beautiful and sweeping and tender.

I have to fight her paintings for space when I visit now, and move them off the bed in the spare room. My brother and I used to share mum’s old room when we visited. Two wooden beds, springs slackened and squeaky, stood stoutly next to one another on the carpet. But we are both too old and too tall to fit there anymore, and with growing older and leaving home the trips I make are sometimes along. The house feels much quieter than when I was young. It used to be a bit of a family affair, complete with cousins and aunts and uncles and great aunts and great uncles, squashed into the dining room around several extra tables and an assortment of chairs. In summer, mass games of rounders and frisbee are had in the cow fields down the hill. We were the youngest, my brother and I, laughed at the most but given easily the most attention. I was too shy to speak to my older cousins much, but my grandmother would smile at me with her twinkly eyes and tell me that I was always her favourite wee Finnuala. I am her only wee Finnuala, I tell her.

I often wonder how she lives up there, alone in the cold hills. She keeps herself company with hoarded belongings from her travels, piled up on every surface until they drown the house, and by singing to herself in her bright, bird-like voice. I can hear her all the way up two flights of stairs from the kitchen when she calls for the cats. She loves to tell us her stories too, as many times as she can, and her life has been long and interesting. Sometimes, she tells us of the years she spent in Nigeria, and the time she sang her way home in the dark to scare the snakes away, across the railway sleepers above the river, and among the cicadas. Then there was the time that a storm lifted the tin roof right off the house, and the other time they all ate tiny green insects instead of peas, for it was too dark to see in the evening, and the children had wondered why the peas were so crunchy and bitter. Their years here were almost equally as interesting, swimming in the moor-lakes after school and spending summers in a caravan driving all the way across Europe for the sake of adventure, as far as the Black Sea and back.

So when we visit we sit together, and listen to her, and look at the things she has collected over the years that turn the house into a relic of past decades. In the ageless beauty of these hills, modernity feels as though it has only skimmed past. There still remain the ruins of tiny cottages along the road here, warped by tree roots. Some are still bound by four walls, still lived in, though the windows are dirt-stained and the roof-slates covered in moss.

The hedgerows along these lanes have looked the same for as long as I can remember. Gnarled branches curl into a carpet of moss and lichen, and bleed the light from the sky. Ferns choke the driveway up to the house, growing over the tarmac to make a tunnel of green, and sometimes it is hard not to feel swallowed by the heady greyness that presses the sky down onto the treetops. Mossy greens tumble down the fields into the lake, and water trickles down into cracks in the earth. A dog will bark, distantly, and the branches of the firs will brush the air aside. Then a chunk of cloud will dissolve, and a brief glancing ray of sun will shiver down onto the lake.

This place will not remain the same, and that is why I am writing this. A piece of my history is still buried here, and when the house falls around it I might never be able to dig it out again. I must try to understand it and remember it as well as I can, even when the familiar begins to blur in water-stains. I will memorise this place as firmly as I can before it is gone. It is funny, the way that parts of my childhood have come to haunt me again. Some people cast themselves apart from their younger selves, and become entirely separate, but I cannot do that. I have, in fact, begun to come back to the early years of my life. Those years were more formative than I had realised. This place is more formative than I had realised.

When the walls have cracked apart, and the kitchen dissolved into the bog, and the belongings spread between the family, I must remember everything that I can.

I will have a picture of it all in my head.

Featured image: by Finnuala Brett

Where does your family history take you?