By Ellie Spenceley, Second Year, English Literature

Sam Levinson’s Malcolm and Marie (2021) seems at first to be a metafictional narrative about stories, and how we tell them. Presented to us in all black-and-white and filmed in one location, the film seems simultaneously ambitious and yet lazy in what it is trying to say.

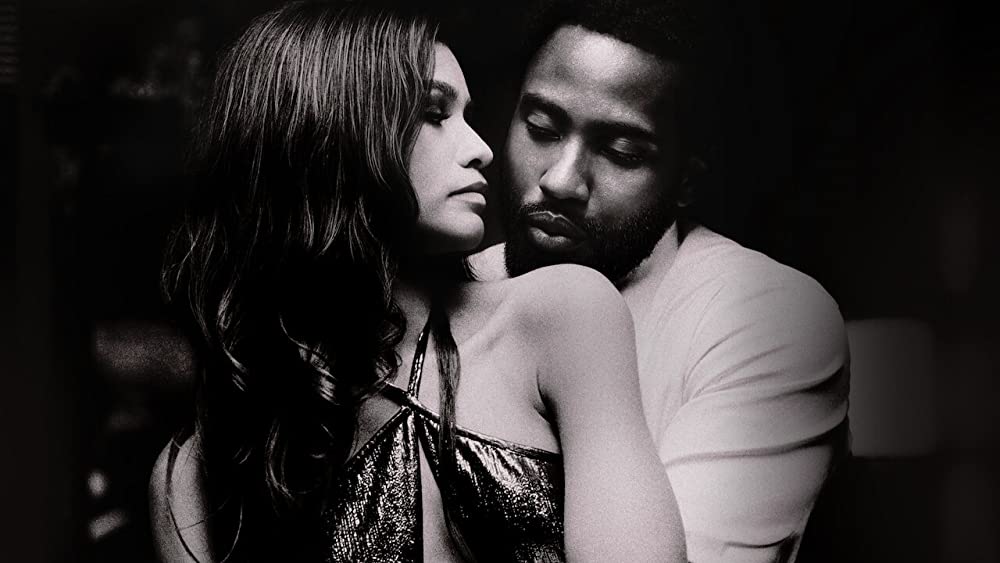

Levinson attempts to use the relationship between the two titular characters to verbosely explore ideas about artistry, drive, identity politics, and the validity of film criticism, but as the credits roll, one is still left pondering what was actually said. Dazzling performances from both Zendaya and John David Washington could sway one into giving a more appraising review, but upon reflection it seems to fall flat, appearing overly self-indulgent and out of touch despite its calls for authenticity and character complexity.

The film begins with the couple arriving home from Malcolm’s film premiere. He is elated, in a world of his own, having received an abundance of praise for his film about a 20-year-old woman’s struggle with drug addiction.

He makes witty comments about how the film was received by white critics, and how he envisions their subsequent reviews to be reductive attempts to ‘frame [the film] through a political lens’ simply because he is Black, and the main actress is Black. It seems promising: a discussion about the ways in which contemporary rhetoric tries to frame everything made by a Black artist through the lens of Black struggle. This potential fizzles out however as the film goes on, as lots of thought fragments are uttered, but none brought to a satisfying end.

The more Levinson attempts to cram in, the less we as an audience are able to get from the film as a whole. At times one begins to empathise with Marie and the issues she verbally labours upon surrounding troubled womanhood and being the unnamed muse of a man commended; her trauma, shame and guilt being used by Malcolm to tell an ‘authentic’ story.

Before this leaves residue, however, we are diverted to obtuse rants by Malcolm about the pretensions of film criticism, about what drives a filmmaker, what gives them integrity. An attempt by Levinson to be profound perhaps, but the whole endeavour seems ironically self-reflexive and futile. What is the purpose of these soapbox speeches, what do they achieve when they are unravelled as soon as they are put together?

The film is tiresome in how sporadic it seems to be to no concrete end. If authenticity is what is being grasped at, the film seems to fall short as the endless monologues appear too artistically crafted to be the words believably uttered by a passionate couple under strain.

As far as criticism for the film’s intentions can go, there is room for commendation at the ways in which Washington and Zendaya portray the troubled Malcolm and Marie in all of their ups and downs.

The main drama of the film stems from Malcolm forgetting to thank Marie in the speech made at his film premiere. From this we see frictions unravel that, not without flaws, present to us an exploration of themes of mental health, recovery, emotional trauma, drug addiction, art, meaning, connection and the many elements that make up love.

There is no doubt that something will be touched upon in one of the many monologues that will strike a personal chord in you, even for a moment. What does love look like? How does it react to antagonism? Can it be vicious? Can that viciousness be subdued in a moment of genuine tenderness? When Zendaya’s character Marie tells her lover that ‘once someone is there for you and once you know they love you, you never actually think about them again’, the question of whether indifference signals a relationship’s subtle turn for the worse lingers, and tinges the rest of the film’s many conflicts and reconciliations.

Early in the film Marie claims she has a ‘masochistic’ streak, and later on Malcolm asks her why she ‘love[s] being hurt, traumatised and eviscerated’.

Pain and its reasoning do appear to be an interesting motif, with tangential concepts of solipsism, identity, and theatricality and cushioning its centrality. Is it better to be a perpetual mystery, or put your heart and soul out in the open for anyone with the momentary impulse to rip apart? This is a question even Levinson does not seem to have the answer for, given the films many argumentative inconsistencies. As discussions about fundamentals of love drag on, we are left with more questions than answers. What comprises the self? What do we need, and what do we merely want? How distinct a quality is love? How do we create art that we can truly call our own?

As the night never ends and arguments prove futile, the film does start to appear a tad too long and you are left pleading for the pair to simply go to bed and face their problems in the morning.

Seven films to look out for in 2021

Vanessa Kirby gives a devastating performance in 'Pieces of a Woman'

Marie foresaw it when she says early on that ‘[n]othing productive is going to be said tonight’, and while artistically applaudable and scattered with captivating moments of intimacy, her statement is true. Puzzlingly so for a film so dense with dialogue, Malcolm and Marie says little that stays with you for longer than the film is on your screen.

Featured: Netflix, Inc.

What do you think of Malcolm & Marie?

Epigram Film & TV / Twitter / Instagram