Bergman's films are well-known for their dealings with awe-inspiring themes and never shying away from some of the bleakness of human life. What better films to see in the upcoming weeks leading to exam season.

Ingmar Bergman is a loaded name amongst fans of cinema. A common perception of the celebrated Swedish filmmaker’s work is that it is heavy, self-serious, even pretentious. Yet while his work certainly deals in portentous, weighty themes such as humanity’s insignificance, the absence of God, and psychosexuality, his work is also laced with lashes of wit, humour and warmth. Bristol’s Watershed will be exhibiting a small handful of the acclaimed director’s sixty films over the next month, providing some perfect entry points to the work of one of cinema’s most important auteurs.

Watershed’s selection elides some of Bergman’s most widely lauded films; neither his Academy Award-winning The Virgin Spring nor any of the films in his epic Faith Trilogy are included in the season. Rather, the season offers some lesser known early works such as Summer with Monika and Smiles of a Summer Night.

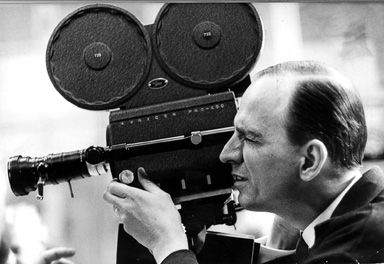

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Both have their merits - the gritty, urbane photography of Summer with Monika is a treat, while Smiles of a Summer Night is one of Bergman’s few comedies, one where he first explored many of the themes that would define his career. Yet neither are amongst his best works, functioning more as intriguing curios for existing Bergman acolytes. Indeed, newcomers approaching these films may be somewhat perplexed as to what the fuss is all about.

Bergman would not come into his own until 1957, when two of his greatest films were released. The more accessible of the two, Wild Strawberries, is perhaps the perfect entry point for cinemagoers interested in Bergman’s work. The film depicts a road trip across Sweden undertaken by an embittered, geriatric professor and a ragtag assortment of younger people he meets along the way.

No explanation could satisfy the bizarre, beguiling nature of the nightmarish imagery Bergman conjures.

It is the first of Bergman’s films to truly play with time and memory, experimenting with dreams and flashbacks and the way they meddle and collide with reality. It’s also one of Bergman’s most uplifting films, a beautiful meditation on the torment of ageing that ultimately finds meaning and value in one’s twilight years. Delving deep into the human psyche whilst never losing sight of the melancholic warmth and joy of human connection, it is the perfect introduction to Bergman’s work.

The second of Bergman’s two 1957 hits, The Seventh Seal, is easily his most famous. The film’s iconic opening image - a medieval knight playing a game of chess against the grim reaper - has been incessantly parodied. Yet it’s still an incredibly powerful image, one that perfectly introduces the surreal, existential hell-scape of Bergman’s plague-ridden Sweden.

The film’s world is endlessly memorable, with Sven Nykvist’s brutally sparse, stark black-and-white photography perfectly capturing Bergman’s hauntingly alien imagery. The danse macabre that ends the film is an image of uncompromising desolation, casting human figures as the dainty playthings of a world too big to comprehend.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Yet one aspect of The Seventh Seal that is perhaps less talked about is its radiant warmth. Despite appearing morose and sinister, the film is imbued with a wicked sense of humour. The cheeky nihilism of Gunnar Björnstrand’s Jöns grounds the film’s celestial themes in a human aspect. Likewise, there are moments of genuine sincerity and beauty in and amongst the despair.

A shot early in the film of the Virgin Mary walking a baby Jesus is reminiscent of Wild Strawberries in its idyllic, nostalgic vision of the past. Indeed, it’s these little moments of warmth that justify the film’s profound philosophical reasoning and rambling, knotty structure.

Bergman’s finest moment, however, came in 1966 with his magnum opus, Persona. There aren’t many films that can feel this shocking, this bold and this modern over fifty years after their release. In some respects a psychological horror film, in others a postmodern interrogation of identity and in still others a commentary on the voyeuristic nature of cinema itself, Persona has confounded and befuddled audiences for decades on end.

Liv Ullman, lead actress in Persona.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Following a nurse named Alma who is assigned to care for a famed stage actress, Elisabet, who has stopped speaking, the film opens with a series of viscerally haunting images that perfectly set the tone for the harrowing 90 minutes that follow. To watch the opening to Persona is to be immediately plunged into a world strange and unfamiliar to any other ever portrayed on-screen before or since. The story of Alma and Elisabet that follows is by turns terrifying and tragic, alien and human.

Persona is not a film to be understood but rather experienced. No explanation could satisfy the bizarre, beguiling nature of the nightmarish imagery Bergman conjures. It is the very pinnacle of Bergman’s oeuvre, surely one of the finest films ever made, and one that demands to be seen on the big screen.

Watershed’s season concludes with the acclaimed yet overrated Cries and Whispers. The only Bergman film to be nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars, the film serves as a massive change in pace and tone from Bergman’s earlier pictures. Where Persona is an all-out assault on the senses, Cries and Whispers is glacially paced, uncomfortable to watch and almost inaudibly quiet. Following three sisters, one with a terminal illness, and their doting maidservant, the film examines the four women’s tragic pasts and bleak present, before pointing towards their horribly cynical future.

Compared to the nuance and depth with which he plumbed the extremes of emotional and existential distress in his earlier films, that point can only come across as feeling mundane.

There are certainly some moments in* Cries and Whispers* where Bergman recaptures the strange magic of his earlier work, particularly in a stunning dream sequence towards the end that oozes existential despair.

Yet much of the suffering and misery depicted in the film ultimately feels banal, Bergman not constructing any greater point from his depiction of physical and emotional torture beyond ‘life is horrible’. Compared to the nuance and depth with which he plumbed the extremes of emotional and existential distress in his earlier films, that point can only come across as feeling mundane.

Bibi Anderson, Alma the nurse in Persona and Liv Ullman

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

As with all Bergman films, there are still a few merits to Cries and Whispers. Yet it’s not an easy film to watch, and newcomers would be better served with any of the aforementioned films as potential entry points. Bergman is one of cinema’s finest filmmakers and even missteps like Cries and Whispers are fascinating in their own right, even if they don’t match the giddy heights of films such as Persona.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons