By Vilhelmiina Haavisto, Deputy Science and Technology Editor

World AIDS Day was first observed on December 1st, 1988. 30 years on, research to find a cure for HIV continues to make advances.

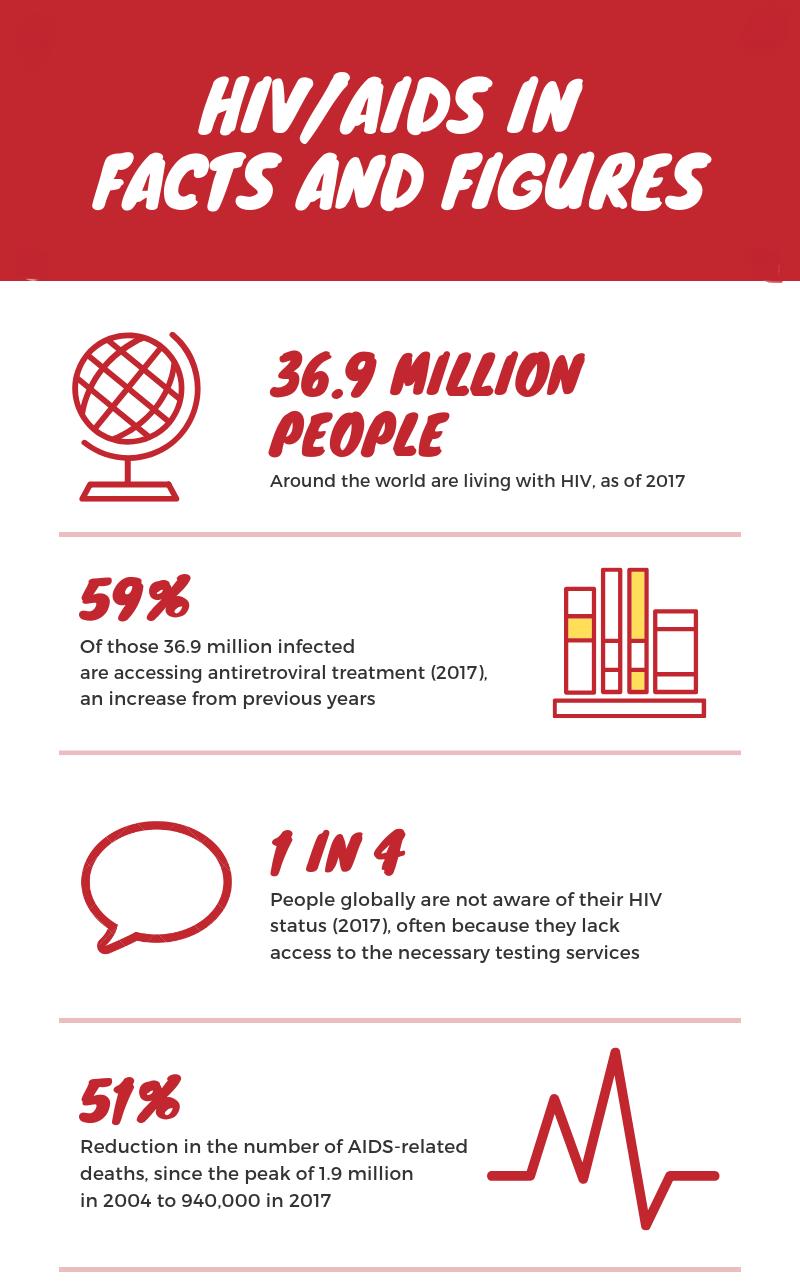

Over 100,000 people in the UK and an estimated 36.9 million people worldwide are living with HIV. HIV/AIDS has been identified as one of the most destructive pandemics in history and has claimed 940,000 lives in 2017 alone. Though HIV-positive, ‘undetectable’ individuals can live long lives thanks to antiretroviral treatment (ART), which suppresses the virus and prevents its transmission, there is still no cure – however, researchers around the world are working to change this.

Image by Vilhelmiina Haavisto

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) attacks the targets the immune system’s ‘helper’ cells which activate antibody-producing cells during an immune response. Once these cells are destroyed, antibodies that normally combat pathogens entering the body can no longer be produced. The immune system is weakened, which leads to recurrent infections. There are two main types of HIV: HIV-1 is the most widespread globally, while HIV-2 is less common and pathogenic. AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is a long-term consequence of HIV infection and can take years to develop, during which an infected individual is the ‘latent stage’: infected, but still harbouring a relatively strong immune system. AIDS is diagnosed once the body cannot fend off illnesses that a healthy immune system would have no trouble with, such as PCP, a rare lung disease.

There are many reasons why HIV/AIDS has proved difficult to cure. Even with ART, the virus has been found to persist inside other kinds of white blood cells and re-emerge from these ‘reservoirs’ after treatment is stopped. This makes completely eradicating the virus from the body complicated, as these white blood cells have long lifespans and are incredibly abundant. The main goal for researchers is rooting out the virus when it is undetectable; just two emerging approaches to combat HIV are antibodies and gene editing.

A “Functional Cure”

Earlier this year, a team at the University of Hong Kong’s AIDS Institute reported that they discovered a “functional cure” for HIV-1. This breakthrough involved a new, bi-specific antibody that could be used for both the treatment and prevention of HIV infection. The team tested their antibody in humanized mice, engineered to carry functional human genes, and found that it was able to neutralize all 124 HIV-1 variants tested, which no current vaccines can achieve. They also observed that the antibody reached the virus reservoir and eliminated infected cells there.

The paper detailing the discovery was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, and thanks to this success, the researchers are pushing for further clinical development of the antibody, eventually leading to use in people living with HIV. However, though this was hailed as a “functional cure”, it is still a long way from clinical implementation, and Chen Zhiwei, leader of the team at the University, believes that it could take up to five years before the antibody can be trialled in humans. Nevertheless, it is a promising step in HIV research

Genetic Engineering

Earlier this month, a shocking claim was made by He Jiankui, a researcher at the Southern University of Science and Technology of China. He announced that genetically engineered an embryo to disable the pathway that HIV-1 uses to infect cells: the twin girls born as a result are reportedly healthy, and in theory, immune to HIV. The research has not been published or independently reviewed at the time of writing, and the Southern University has noted that He has been on leave, and that they were unaware of his controversial research.

In theory, such genome-editing techniques could be used to prevent HIV-1 infection on the genetic level. He claims to have used the CRISPR–Cas9 genome-editing tool to disable a gene called CCR5, which encodes a protein that allows HIV-1 to enter and infect a cell. However, the necessity of editing embryo genomes, rather than those of HIV-1 patients, has been questioned. Fyodor Urnov, a researcher also studying the CCR5 gene, works with HIV-1 patients and says that “there is...no unmet medical need that embryo editing addresses”, and that there are “safe and effective ways” of using genetics to prevent HIV infection. One such way which Urnov has worked on involves disrupting CCR5 in lab-generated cells, and then transplanting these cells into infected individuals which were, in his 2008 paper , mice. His research found that the mice with edited cells had lower viral loads, and higher numbers of ‘helper’ cells, than those without, suggesting that this kind of gene editing could have real potential in treating and preventing HIV infection.

Final Thoughts

It is clear that HIV research is moving towards promising results, and that scientists are working hard to find an eventual cure for HIV/AIDS. Only time will tell what form this eventual cure takes, though. In the meantime, the World AIDS Day campaign reminds us that there is still a “vital need to raise money, increase awareness, fight prejudice and improve education”, and calls on us to challenge “HIV-related stigma and discrimination”, both on December 1st and all year round.

Featured Image:ProcuraMed Saúde/ Flickr

Will you #RockTheRibbon on December 1st?

Instagram//Facebook//[Twitter(https://twitter.com/EpigramPaper?ref_src=twsrc^google|twcamp^serp|twgr^author)