By Jacob Rose, Third Year, Film and English

This year, I've become a bit of an amateur expert on Aki Kaurismäki, the director of the incredibly charming Fallen Leaves. Having perused through his earliest films, I've become a slight megafan of the style of Finland on screen. With this in mind, i hope it gives you more urgency to see Fallen Leaves at any point in the future, when I tell you just how stunningly Kaurismaki demonstrates the best of romance, the best of life, and (maybe a tiny little bit) the best of what film as a medium can do.

To call Kaurismäki’s films idiosyncratic would be an understatement, as it isn't just a visual language that is repeated: entire setpieces and narratives are taken from his own filmography, informing an incestuous collection of films that could never feel separate from the other. Fallen Leaves takes major narrative beats from at least 20 years of Kaurismäki’s filmography, following a tale of beginning romance amidst the indents of unstable careers, distant violence and addicition. From Shadows in Paradise (1986) to Drifting Clouds (1996) to The Man Without a Past (2002), these events have all been shown previously, just not in this order. It bears a stench of being derivative, unimaginative, self-effacing, lazy - and yet, in the span of his filmography, it gives the opposite: charm, comfort, and a loving embrace.

Because of (and beyond) this, Kaurismaki's worlds feel defined in a blurred space, one directly between a horseshoe of the UNCOOL - COOL binary. The characters are usually, to put it harshly, the archetypical losers. Trapped in dead-end jobs, smoking any chance they can, there is an urgency for a call for action, for change. this call isn't necessarily on mute in Fallen Leaves, but it'd be fair to say the phone is set to vibration only. The two working-class lovers are set to standby, feeling slightly dead, in part due to over-dulled performances that enhance every actual act of love. The start of the show then, perhaps, is Alma the Dog, playing Chaplin the Dog, whose expressiveness evokes anything that lover Ansa (Alma Pöysti) might be too tired to let out.

Prioritising a perspective of small actions, Fallen Leaves brings colour, energy, character, into the mundanity of general life. It points to what I'll crudely named Proletariat cinema (named after the director's 'proletariat trilogy'), a cinema that emphasises a working-class perspective. Work lives and spaces are shown, explored, every much a part of the filmic narrative as the romance itself. There is life in the spaces that would usually be defined as the purely mundane - a thematic primitivism that feels emotionally real, and refreshing.

The visual style of Fallen Leaves especially helps this direction: tinges of colour are splashed throughout, painting even the dullest space with colourful intrigue. Here, the stagnant lives of our protagonists aren't just dull; they spring out of the space itself. This is beautifully prioritised in the meet-cute, a Karaoke bar with wonderfully tight mise en scène, making any move an act of passion.

In such, everything in Fallen Leaves feels meaningful, joyful, cinematic - nothing is unworthy. A turning of a switch, a conversation between strangers, a trip to the cinema, it all can mean so much, if given the time, and I’m so very glad that it is here.

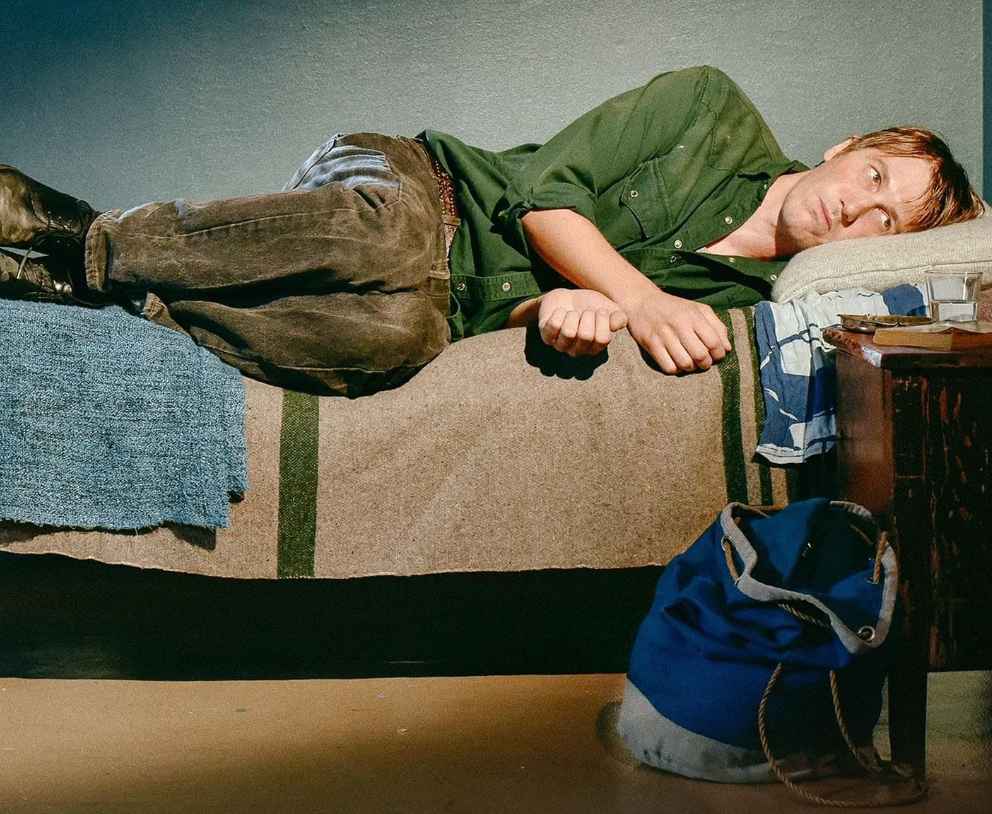

Featured Image: IMDb

Are you familiar with the work of Aki Kaurismäki?