By Ella Woszczyk, Second Year English

Glastonbury organisers were perhaps surprised when this years’ poster line up (revealed March 3) received public backlash due to the all-white-male headliner selection. Guns ‘N’ Roses, Arctic Monkeys, and Elton John grab the top Friday, Saturday, and Sunday performance slots, whilst the festival's array of female artists fill supporting roles.

American singer-songwriter, Lana Del Rey, was particularly vocal about her disappointment. Despite brandishing over 40 million monthly Spotify Listeners, the alphabetised graphic originally featured Lana on its seventh row, beneath artists with notably smaller followings. Taking to her private Instagram shortly after the release, Lana expressed her reluctance to still perform: ‘Well I’m actually headlining the 2nd stage. But since there was no consideration for announcing that. We’ll see’.

Glastonbury’s line-up graphic has since been updated to reflect the status of ‘major’ artists, but it has prompted further conversation. What would a sufficiently diverse line-up look like and are festival organisers doing all they can to deliver such?

Annual music festivals have become highly anticipated and sought after events for all age groups and demographics. A report run by Statista identified just under 34 million attendees in 2019 in the UK alone. A report run by Ticketmaster in the same year also identified that ‘29% [of the 4000 UK festival punters interviewed] feel there is not enough diversity in festival line-ups, with 47% wanting better gender representation among artists appearing. Three in ten (29%) also say that the gender balance of line-ups is something they actively consider when choosing a festival to attend.’

Whether your music preference be Rock, Electronic, Alternative or Hip Hop, festival organisers have a duty to create inclusive environments that reflect their diverse audiences.

Festival diversity, however, cannot simply be limited to gender and race considerations. As outlined in Glastonbury’s current diversity statement, organisers must also take into account ‘ethnicity, visible or unseen disabilities, sexual orientation, heritage, religion, age, family status, and social class or education’. Ensuring fair representation of all these social groups would seem to make the diversity task a challenging one.

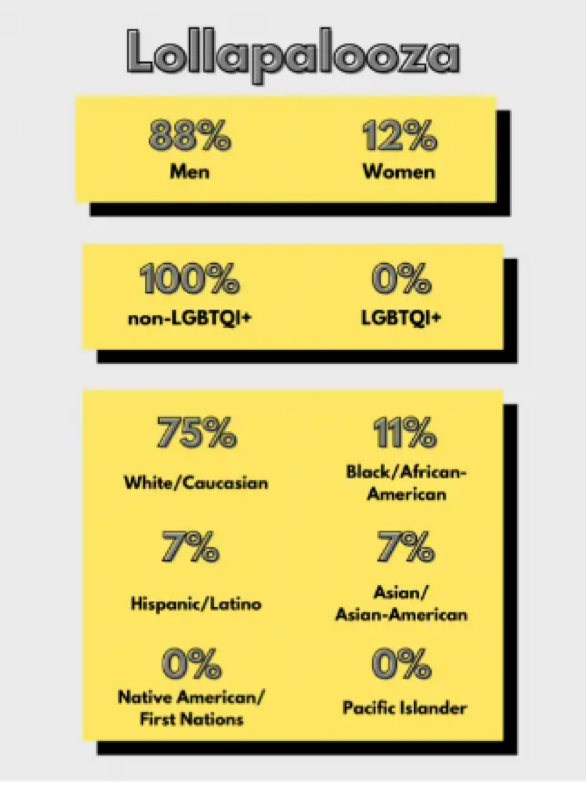

Chicago’s largest festival, Lollapalooza, attracts crowds of up to 100,000 each year, and yet the digital platform ‘6AM’ tracked the events’ glaring diversity imbalance in 2021. Focusing on the demographics of its dance artists specifically, ‘6AM’ tracked a disparity of 88% male artists - 100% of which being non-LGBTQI+. There was also a deficit in the event’s BAME representation, with 75% of artists being White/Caucasian. These statistics were comparable with North-America’s other high-profile electronic festivals such as EDC Las Vegas and Bonnaroo.

Sziget festival in Budapest is one of the largest in Europe, and despite hosting a ‘global family’ of ‘Szitizens’ from over 100 countries, all 7 of its 2023 headliners are white musicians. Though Sziget’s headliner gender ratio is a reasonable 42% of women, the UK’s Reading & Leeds festival in comparison claims Billie Eilish as its only female headliner. Eilish is actually headlining both Sziget and Reading & Leeds, which perhaps shows that festival planners are struggling to secure a variety of viable female headliners.

Glastonbury’s co-organiser, Emily Eavis, has defended this lack of diversity, telling The Guardian that the music industry ‘needs to invest in more female musicians to create future headliners’. In 2020, Eavis also described her difficulty working with bookers and agents, explaining: ‘There’s a whole brotherhood which is so tight. It’s impenetrable.’

What is clear from these examples, is that festivals still have a long way to go to be deserving of the label ‘diverse’. But, actions are being taken to work towards improvement. As part of the PRS Foundation’s Keychange initiative, more than 150 festivals from across the globe have pledged a commitment towards a 50/50 gender split in their line-ups. ‘Book More Women’ is another online movement protesting for social equity, with the public pressure prompted from their campaigns forcing festival organisers to take responsibility when monitoring their diversity targets.

Though Sziget’s claim of having a ‘global family’ is somewhat diminished by its majority of white British/American headliners, a smaller festival down the road from Bristol in Wiltshire is doing more to live up to its identification as ‘The World’s Festival’. Headliners for the 2023 Womad festival are evenly split with White and BAME, with the small selection of 6 artists boasting musicians from Nigeria, Portugal, and Jamaica, as well as England. Might it be easier for festivals to achieve diversity when organisers are under less pressure to book the most recognisable names?

It may be unfair to solely blame the festival runners for slow improvements in line-up diversity. Historically, men have dominated the music industry, and so these large-scale events, which are under annual pressure to book music ‘legends’, are working from a restricted pool. Disparity within the music industry is a far-reaching concern that festival organisers cannot overcome simply by themselves.

To return to the insights offered by Eavis, more needs to be done socially and financially to help marginalised groups reach high-profile status as musicians. More work needs to be done from the ground up before festival organisers can attempt to successfully represent everybody in a white-male centric industry.

Featured Image: Colin Lloyd | Unsplash

What do you think about festival diveristy?