By Julia Riopelle, SciTech Editor

In this second interview of ‘Diversity in STEM’, we speak to PhD student Lingfeng Ge. This interview series aims to highlight BAME experiences in academia in order to have more representation in the field of STEM.

Lingfeng Ge completed her BSc Chemistry at Xiamen University in China. She then went on to complete two Masters abroad; an MSc in Chemistry at the University of Manchester and a joint Masters programme, ‘M2 Frontiers in Chemistry,’ between the University of Paris Descartes and University of Paris Diderot. Now Lingfeng is in the third and final year of her PhD at the University of Bristol, where she is researching photodissociation dynamics with coulomb explosion imaging. I had the pleasure of interviewing Lingfeng about her experiences as a Chinese woman in chemistry and the challenges she has faced whilst being abroad.

When did you first develop an interest for chemistry?

My interest for chemistry started in middle school, where I noticed it was much more enjoyable than any of the other subjects I was learning. I think this was because my middle school chemistry teacher was really inspiring.

Are there any noticeable differences in studying chemistry in China versus the UK?

It’s hard to compare, because I did my undergraduate in China and postgraduate abroad. Although I would say that in China there are too many students and labs tend to be overcrowded. Each academic needs to oversee many students, whereas here, at least in my PhD, the groups are small and you get a lot more attention. The methodologies and work ethics in research are pretty much the same.

However, I’d say the main noticeable difference in my experiences in China versus here is more personal. I’m abroad here. I’m alone here. I’m far away from my family and friends back home. Far away from what is familiar to me. So life is much more difficult here. I have been trying to make friends, though I find it a lot easier to make friends with Chinese and other international students, than with UK students. I think it’s just because a lot of UK students already have a stable network here. From my own experience, I have noticed home students do not have a strong desire to make friends from abroad - particularly with people from very different backgrounds.

How do you cope with the language barrier in university and research settings?

I agree that the language barrier is an obstacle, though what makes my life a lot more difficult is the cultural barrier. It’s hard to make friends with domestic students. Sometimes I also feel like UK students don’t try to understand students of a different cultural background. They just find me odd.

In your undergraduate degree did you only read papers published in Chinese journals or were your resources very diverse? How does this compare with resources available at the University of Bristol?

At Bristol I can draw information from papers from all over the world. This is because the global language is English and so researchers who want to get their work noticed by a global audience will write in English. If research groups publish in their own language, the range of audience is much more narrow.

Back in China, I didn’t have the chance to read papers published in English, as our resources were limited to Chinese databases. This is usually because the ones in English are much more expensive than the Chinese ones and many Chinese universities cannot afford subscriptions to them for every student.

What inspired you to undertake a PhD as a potential first entry point into academia?

In my undergraduate and Masters degrees I found that I simply have a passion for research - the discovery of new things! I still think conducting research is far more interesting than anything else! My masters at the University of Manchester was very computational based, whereas I got to work with lasers at the Laboratoire de Chimie Physique in Paris, which was much better. My experience at the Paris lab is what triggered my interest in laser and spectroscopy.

So in order to advance my academic career and make myself more employable, I thought that was naturally the next step to do. It also allows you to be a group leader in research, as well as a follower. I thoroughly enjoy the research right now, so we’ll see whether I go into industry or an academic at a university, who may lecture on the side! I am one to chase opportunities, so we’ll see where it takes me!

Most downloaded in 2018 from Structural Dynamics: Photodissociation of aligned CH3I and C6H3F2I molecules probed with time-resolved Coulomb explosion imaging by site-selective extreme ultraviolet ionization. https://t.co/5UKOJRDwjd #AIP_SD

— AIP Publishing (@AIP_Publishing) December 28, 2018

Why did you choose to do your PhD abroad rather than back home?

I am lucky, most students in China do not have the money to go abroad, so I am definitely privileged. Although, amongst the middle class in China, the majority will try to complete a degree abroad. We are very curious about the world outside of our own country.

Originally I was planning to do my postgraduate in the US, however I heard from Chinese students there that they experienced a lot of racial and gender discrimination there. Whilst having its own issues, I think Europe is generally less racist. It also seems that Europe seems less competitive with post-graduate positions and they encourage more collaboration between researchers.

PhD usually attracts more international students, what is your supervisor group like?

In my supervisor's group at Bristol, it’s mainly British students as well as the supervisor himself. Over the last three years there has been one other international student, however they are Australian, so I don’t think they had much difficulty relating to the other students. I was quite surprised all were English - I was expecting many more international students!

You touched on the topic of gender discrimination before. In my previous interview with Dr Leanne Melbourne she mentioned the lack of women in chemistry, do you have any comments to add to that?

In my bachelor's in China there were actually more female than male students in chemistry. However, coming to England I was surprised, as in my supervisor’s PhD group I have been the only female in the last three years. I don’t really know why. Maybe that is the difference between undergraduate degrees and postgraduate degrees? Here in Bristol I have particular noticed whilst helping out in the labs, that amongst the bachelor's students, the ratio of girls to boys is roughly the same. However, in the PhD programme here, there are a lot more boys than girls.

Is there any advice you’d like to give to girls in chemistry entering a very male-dominated research environment?

Try to find a PhD group that isn’t only boys! I’m going to be honest - being the only female is very difficult. It is often hard to get people to listen to me. I wonder if it’s because I am the only woman, or because I am the only international student, or because I am the youngest in the group, or even because I am Chinese. All these could be the reason behind the arrogance I face. I am not listened to and I don’t understand why. Perhaps I am just too different to them. Though despite this, my passion for research and chemistry is stronger than the challenges I face.

Diversity in STEM: a conversation with Dr Leanne Melbourne

First-of-its-kind undergraduate research journal launched by Bristol postgraduate student

Could you describe the research you are conducting in your PhD?

Basically these past three years I have been using lasers to blow up molecules! By blowing them up we are able to study the fragments and structures of these molecules. There are actually no current applications for this, but the aim is to identify how molecular structures can change and evolve with time. I use a laser to excite a molecule in its gaseous phase and see how it changes in a matter of femtoseconds - one quadrillionth of a second. As molecules are invisible to the human eye, it is very difficult and delicate work.

How do you see the change if it’s happening so fast? What equipment and methods do you use to study and visualise it?

After the molecule is blown up, the fragments fly towards a detector and light up. If you look at the positions of the molecule fragments, which appear as spots on the detector, you can get an image and interpret it.

We compare the detected image to the original molecular structure in order to mark our the change occurring over this minuscule time period. The research involves a lot of data analysis and imaging skills, which we do by writing programs to create computerised models to help visualise what exactly is happening.

That is what I find exciting though, being able to observe chemical reactions that happen in a matter of a femtoseconds! It’s exciting because of the potential of what we discover!

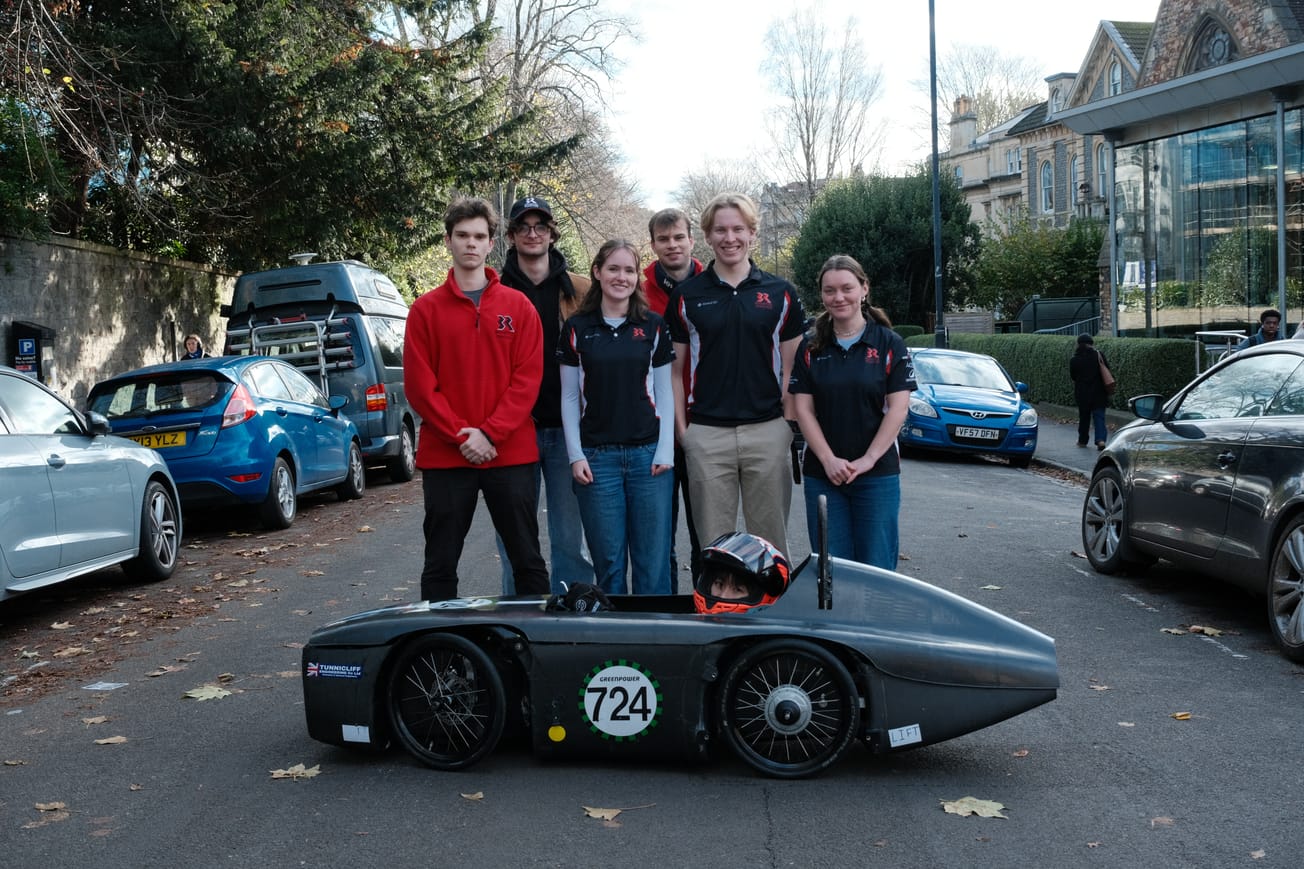

Featured Image: Flickr / whatchamakallit

Are you a BAME professor or PhD student in a STEM field? Reach out to the SciTech team to share your experiences!