By Olivia Howard, Geography, Third Year

In light of International Womens’ Day, and as cities strive to enhance inclusivity, incorporating gender-sensitive urban planning becomes imperative for fostering equitable, accessible, and safe environments for women and all other genders. By 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will live in urban areas - this is a topical issue which will become inescapable for future generations.

Urban planning and design significantly shape the daily experiences of city inhabitants, influencing safety, mobility, economic access, and overall quality of life for people.

Until recently, urban environments have been conceptualised with a male user in mind, often marginalising women and other vulnerable groups. Such an oversight has led to the accumulation of spatial inequalities, where infrastructure, transit systems, and public spaces fail to accommodate the diverse needs of all citizens.

Several factors directly influence women’s well-being in cities; namely safety, security, mobility, transport access, essential services and space utilization.

Poorly lit streets, isolated public transport stops, a lack of pedestrian networks have statistically increased the likelihood of gender-based violence. If these gender-specific behaviours are not considered then safety concerns and worries around social exclusion arise.

Similarly, with women often taking the brunt of caregiving responsibilities with children, complex transport systems, created by steps, interchanges etc. become a barrier to women acting as active citizens within the population. This evidences the necessity for safe, well connected, pedestrian friendly routes to create healthy cities that are welcoming to all genders.

Essential services created through urban design allow women and other marginalized genders to thrive, similarly, employment centres and local childcare facilities need to be readily available. Full-time childcare for children under two can consume up to half of a woman's median earnings as well as increase journey time by over an hour before and after a full-time job every day. This accessibility crisis directly impacts women's participation in the workforce, as many are forced to reduce working hours or leave their jobs entirely. These experiences are pushing for multi-purpose spaces within our cities, where childcare and corporations can be located close to one another.

The question thus arises, how should we implement solutions to these problems?

The first is instituting integrated safety measures in public spaces. Natural Surveillance is a clever way of maintaining street level observation while remaining unintrusive; this is through implementing windows which face out onto the streets, constructing mixed-use developments, and designing transport infrastructure which enhances passive surveillance, such as regular stops on long routes.

Further to this, enhanced lighting which facilitates wayfinding is also a method to increase female safety within cities. LED lighting in pedestrian corridors, transit stations and parks improve visibility and reduce perceived/emotional risk. Similarly, smart technology and surveillance such as CCTV, emergency call stations, app-based safety monitoring through geolocation and features which allow you to share the progress of your journey on apps such as Uber, are all deterrents against crime.

Despite this, distinct perspectives on these interventions still exist. In a world where maintaining ownership of our data seems more important than ever, many believe increased digital surveillance encroaches on human rights and privacy laws.

Similarly, some social groups have commented that the interventions above demonise men, fuelling a culture war, growing the gender divide and increasing political polarity. This has been specifically complained about in relation to female-only sections in trains, female gyms and workout classes. The suggestion is that our population is becoming more divided, rather than united.

Interestingly, an important critique to note within this field is one from intersectional feminists and scholars who have revealed that gender-inclusive planning must account for women of different socioeconomic, racial, and ability backgrounds to avoid reinforcing systemic inequalities.

However, evidence proves that gender-inclusive design can thrive. Vienna is a global leader in integrating gender-responsive planning. The city’s Frauen-Werk-Stadt (Women-Work-City) project reimagined housing complexes by incorporating community-driven design, childcare accessibility, and pedestrian-centric layouts. Vienna’s public transport design prioritizes safety through enhanced lighting, clear sightlines, and station attendants during late hours.

Umeå, Sweden, adopts a ‘Feminist City Approach’. Umeå has embedded gender perspectives into city planning through participatory design. Policies include gender-balanced representation in decision-making processes, redesigning public seating to encourage social interaction, and evaluating infrastructure projects through an intersectional lens to benefit women and marginalized groups. Particular examples which have thrived are underpasses and skateparks, which are no longer ‘dangerous’ or ‘vulnerable’ places for marginalized genders due to increased cross-gender social participation and lighting.

Designing cities with gender-responsive principles is a fundamental step toward creating equitable, just, and sustainable urban environments for everyone.

By integrating safety, accessibility, and participatory design strategies, urban planners can build resilient cities that empower women and foster a nurturing and contented public life. These actions can begin with small adjustments in urban symbolism such as the changing/renaming and claiming of statues, street names, and public commemorations which reflect women’s contributions to civic life, fostering a sense of belonging.

Moving forward, policymakers must prioritize data-driven gender surveys, invest in gender-sensitive infrastructure and institutionalize feminist planning frameworks to transform urban landscapes into healthier, safer, and more inclusive spaces for everyone.

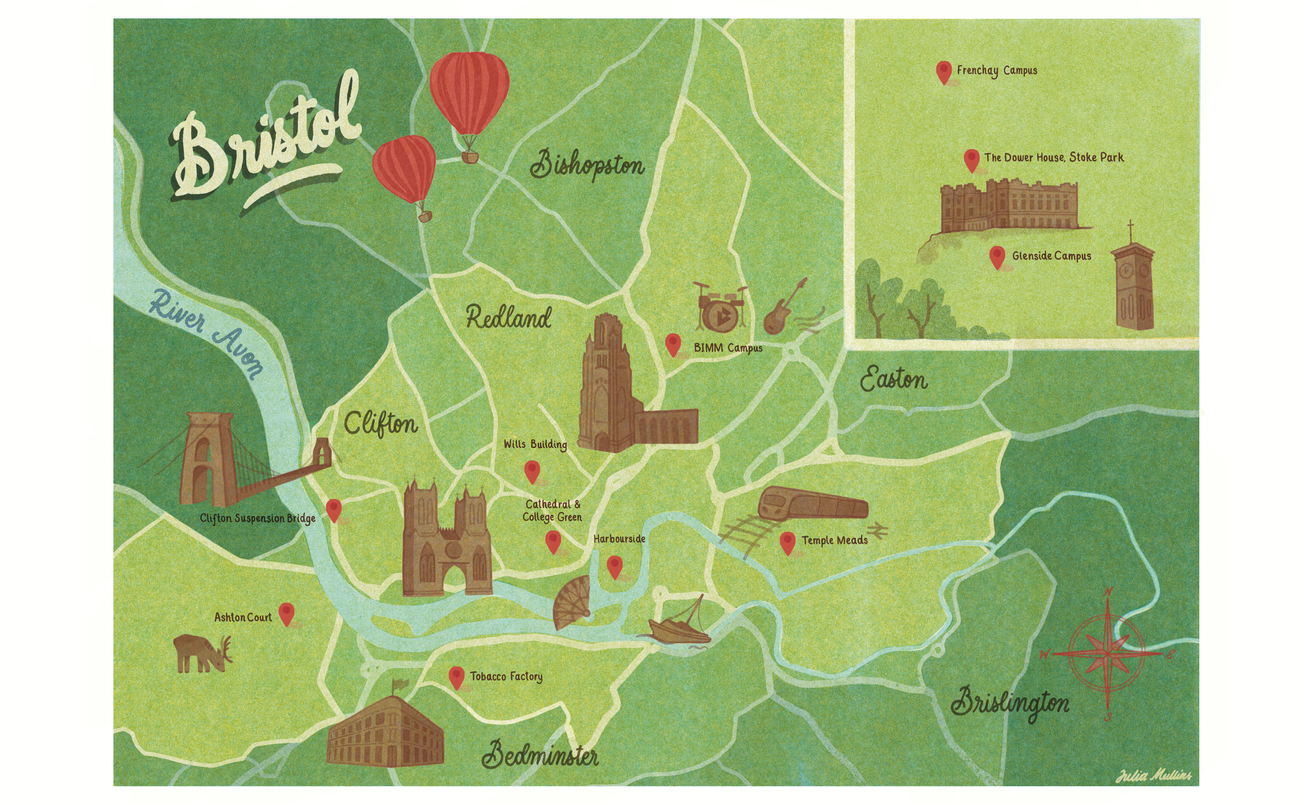

Featured illustration: Julia Mullins