'De-Colstonising’ Bristol – how much has changed since the 2020 statue toppling?

By Mateo Cruz, Third Year Film and English

In 1680, Edward Colston became a member of the Royal African Company, a mercantile company which transported enslaved African people to the Americas. Between 1672 and 1689, the company transported an estimated 84,000 men, women and children. Shackled together and forced into cramped, disease-ridden conditions, an estimated 19,000 people died on these voyages.

With the wealth gained from these enterprises, Colston set up almshouses, governed and financed hospitals, and funded schools to educate local boys. The city celebrated his monetary donation to these projects; his name was given to streets, businesses, buildings, and, as we know, a statue was erected in his memory.

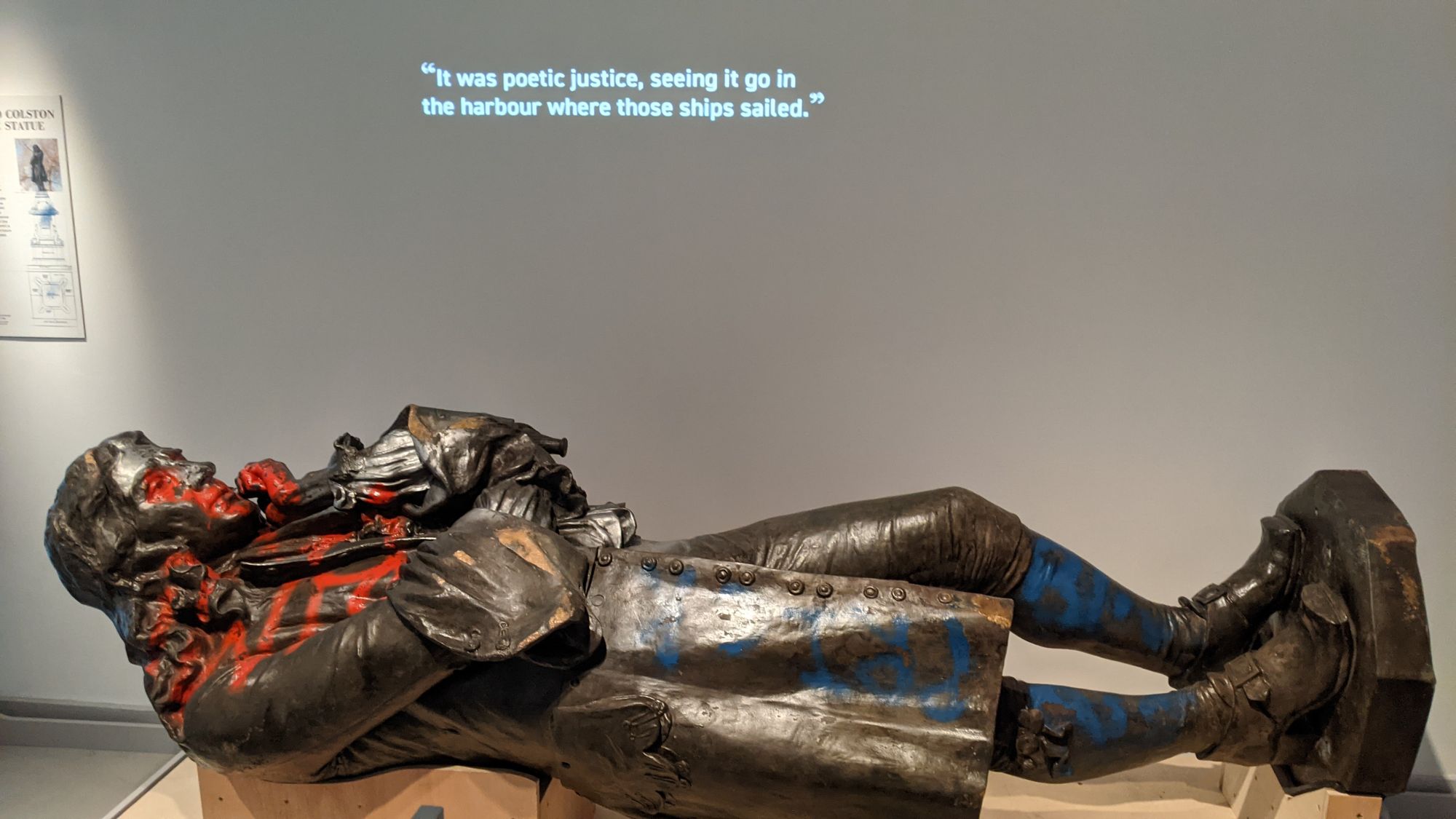

The statue took pride of place in Bristol’s centre in 1895. On it was inscribed: ‘Erected by the citizens of Bristol and memorial to one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city.’ The immense news coverage that the toppling of the statue received in June 2020—which came just a month after the murder of George Floyd and the beginnings of the Black Lives Matter movement—awoke a keener awareness amongst the general public regarding the fact that the same man, who had been celebrated as a philanthropist, also orchestrated and profited from the suffering of tens of thousands of enslaved people.

This sparked a national debate over how to deal with people such as Colston. In one approach, businesses, schools, pubs and buildings have changed their names to dissociate from Colston’s legacy. This has been labelled the ‘de-Colstonisation’ of Bristol.

Just this week, the University created an online survey regarding the renaming of key University buildings: the Wills Memorial Building, Fry Building, Merchant Venturers Building, HH Wills Physics Laboratories, Goldney Hall, Wills Hall and the Dame Monica Wills Chapel.

The survey asks for students, members of staff and the wider public to give their opinion on whether the buildings should be renamed, what they should be named after, and views on how we as a society should assess our colonial links to the past. It is open until December 19th and the results will be made public in February 2023.

89 per cent of the wealth used to found the University of Bristol was accumulated through the coerced labour of enslaved peoples. The University has shown attempts to decolonise its names, but the approach has been inconsistent. In 2017 the University was urged by campaigners to change the name of the iconic Wills Building, named after Henry Overton Wills III whose family’s tobacco company had links with the slave trade. Needless to say, they didn’t change it. A spokesperson for the University issued a statement saying that ‘In our view, it is important to retain these names as a reflection of our history’.

‘Epigram has been assured that the University crest, which still bears a dolphin icon representing the Colston family, is also under evaluation’

However, in 2021, the student accommodation formerly called ‘Colston Street’ was renamed ‘Accommodation at 33’. Epigram has been assured that the University crest, which still bears a dolphin icon representing the Colston family, is also under evaluation.

Efforts have been made to erase Colston’s name in the wider Bristol community. The Colston Society, a Bristol-based society providing funding for schools, officially disbanded after a members poll showed that more of its members wanted the society to disband rather than simply renaming it. Also, following a public consultation involving more than 4,000 people, Colston Hall was re-named the ‘Bristol Beacon’ in September 2020. In November 2020, Colston’s Girls’ School changed its name to Montpelier High School, while earlier this year The Colston Arms changed its name to The Open Arms. Their updated website states that they are ‘A Traditional Pub with Modern Attitudes.’

Despite this, there are examples of Colston’s name still being used around the city. Street names include two Colston Streets, Colston Avenue, Colston Dale, Colston Parade and Colston Road. An NHS community drug and alcohol service continues to work under the name Colston Fort. Colstons Almshouses on St Micheals Hill have not responded to Epigram’s enquiries as to whether they have considered changing their name.

Bristol, of course, is not the only city in the UK to have heavily profited from the transatlantic slave trade. Together with Bristol, London and Liverpool are estimated to have been responsible for 95 per cent of the ships involved in the UK slave trade. The names of prominent slave traders are also inscribed on these cities.

Liverpool’s famous Penny Lane was named after James Penny: the slave ship owner and outspoken opposer of the abolition of slavery. Bold Street is named after slave merchant Jonas Bold. London has many streets named after slave traders: Vassal Street, Holland Grove, Dundas Road, Branfill Road, Cassland Road Gardens and Mulligan Street to name a few.

‘It ‘isn't about rewriting Bristol’s past, but instead to show solidarity and sensitivity to those it may offend’

Since the toppling of the Colston statue, there has been an effort to remove similar statues in London. A statue of Robert Mulligan, Scottish ship owner and slave trader, was removed on 9th June 2020, just two days after the Colston statue was toppled. This was part of London Mayor Sadiq Kahn’s Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm, which aimed to put under review statues and other landmarks in the city.

After months of deliberation, in January the statues of Sir John Cass and William Beckford were removed in Guildhall. Both men had acquired their fortune through the slave trade.

The idea of changing place names has been met with backlash. It was reported by the Mail Online that the Conservative Party Chairman Oliver Dowden criticised Lambeth Council’s plans to rename Tulse Hill, saying that ‘While people worry about the cost of living, Labour councils are wasting their cash on vanity projects like this’. This came after Mayor Kahn offered £25,000 to London local authorities to decolonise their street names.

'It constructs indigenous people, black people, and ethnic minorities as victims of the past.'

— GB News (@GBNEWS) November 23, 2022

Sociologist Ashley Frawley and Former Brexit Party MEP Michael Heaver debate whether Bristol University should rename several buildings due to slavery links. pic.twitter.com/WqqvnxbBIS

Responses in Bristol have been mixed. Briony Williams’s online petition to rename all of the streets in Bristol that bear the Colston name has garnered 1,198 signatures. ‘How can we continue to honour his name in our city when he built his fortune on the lives of thousands of slaves?’, she writes.

‘How can we legitimately still have street names, buildings and schools named after a slave trader? There has to be a change. Enough is enough’.

When Colston Hall was renamed in September 2020, Louise Mitchell, chief executive of the Bristol Music Trust charity that runs the venue, informed the BBC that ‘The name Colston does not reflect the trust's values as a progressive, forward-thinking and open arts organisation’.

University of Bristol to listen to views on building names with links to the slave trade

Sign of the times

In contrast, Bristol Conservative councillor Richard Eddy told the Bristol Post that the decolonizing process was an attempt to ‘Selectively air-brush history’ which ‘betrays absolutely no awareness of the huge debt we still owe to this great Bristolian’. He described it as an ‘Abject betrayal of the history and people of Bristol’.

A third year University of Bristol student told Epigram that the changing of names and the removal of statues ‘Isn’t about rewriting Bristol’s past, but instead to show solidarity and sensitivity to those it may offend’.

The Countering Colston campaign has outlined a list of positive aims to both ‘Commemorate and mourn the people who suffered and died as a result of the slave trade, and recognise the coerced economic contribution that they made’. Instead of admiring historical figures like Colston, the campaign calls for us to ‘Celebrate those who resisted slavery and fought for abolition and emancipation’.

Featured Image: Unsplash / William Chang