By Maddie Bowers, Third Year, Theatre & Performance

The Chinese government are limiting the creative freedom of the blossoming cinemas and independent films in the country, which are otherwise rising in popularity with middle class audiences.

Independent films have long been part of China’s cinematic history – but not often welcomingly on part of the Communist government. Chris Berry notes in a 2017 article for Asia Dialogue: ‘In the United States and most liberal democracies, ‘independent cinema’ is understood in contrast to Hollywood and other mainstream commercial industries. The main thing that Chinese independent films and filmmakers try to be independent of is the state.’

For decades, these daring creatives have gone underground, privately funding their budgets and ducking under the government’s censorship turnstile by not attempting to commercially release their films within China’s borders. Instead, they rely on international film festivals or hushed private screenings. In recent years, however, the Western interpretation of the term ‘independent cinema’ has been reinstated with an authoritarian twist as President Xi Jinping’s government takes a hard stance on soft power.

"The main thing that Chinese independent films and filmmakers try to be independent of is the state."

Chris Berry writing for Asia Dialogue

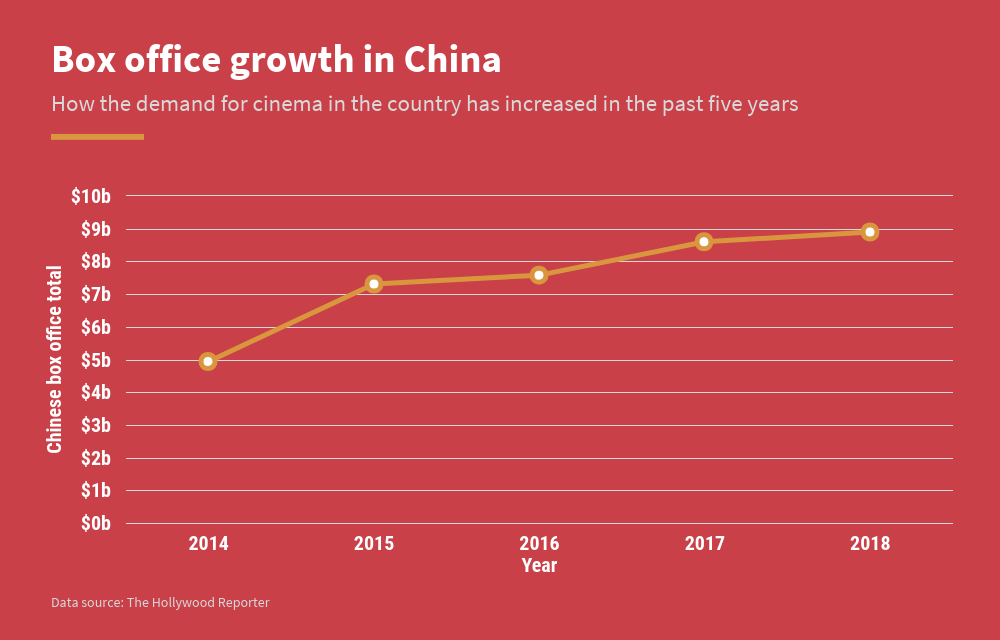

China’s film market is gradually on its way to becoming the biggest in the world, with 25 screens reportedly opening daily. Naturally, Hollywood wants a piece of the swelling pie, but in doing so it has to bow to China’s terms: only 36 foreign films are allowed to be shown in Chinese theatres (although in recent years there has been some leniency).

Additionally, international studios only receive 25 per cent of box office commissions in China, as opposed to 40 per cent in most other markets. So why the great taxes? Well, as most people are aware of, the Communist Party of China has imposed increasing censorship upon the country’s media since coming to power in 1949. This is to conserve its unifying ideology within the mind of its citizens, its arguments being that the integration of Western (mostly American) ideals of democracy and liberty leads to uprising such as that of the Arab spring and hence, in their view, the collapse of peaceful and secure nations.

Therefore, international films must undergo China’s rigorous vetting process, being filtered and chopped until they’re allowed to entice China’s growing middle-class audience. As much as this might bring a tear to your eye on behalf of the Hollywood conglomerates, those that truly have to face the magnitude of this suppression are the often-unacknowledged Chinese filmmakers.

Epigram / Patrick Sullivan

Li Yang, a star of Chinese independent cinema, has consistently had his films banned in China throughout his career. His talent for portraying the raw and gritty reality of the Chinese lower classes has won him a ‘Silver Bear’ at the Berlin Film Festival and ‘Best Feature’ at Tribeca Film Festival, both for Blind Shaft (2003). However, 40 per cent of his latest project has been scrapped by authorities as Li has chosen to work with the censors to ensure Blind Way (2017) receives a theatrical release in his home country.

‘We [filmmakers] survive in a narrow gap,’ Li laments, ‘We are dancing with shackles, but we still want to dance, want to express ourselves. In China, there is a special situation, the censors don't regard the movies as a complete artwork, they believe the movie has the propaganda function, an educational function.’

In March 2018, the government overhauled its department of media regulation and placed TV and radio under the direct control of the state council. Film was given even more special attention as China acknowledged its superior role in ‘affecting the hearts of the people’. It was placed under the command of the Central Propaganda Department.

Famed director Jia Zhangke presents a #ShotOniPhone film on a common #ChineseNewYear journey https://t.co/xUZEs2LgTR

— RADII (@RadiiChina) February 4, 2019

It’s now no longer enough for Chinese filmmakers to adhere to the censors – mainly against graphic violence, sexual scenes, and homosexuality – they now have to actively stand in solidarity with the Xi Jinping’s ideology. This is now increasingly so on the part of independent filmmakers as the population’s taste matures beyond extravagant blockbusters. Artisan cinema more than ever suits the Chinese palate.

Last year, the influential Sixth Generation independent filmmaker Jia Zhangke launched a brand-new film festival in his home province of Shanxi. His aim was to bring a wider audience to artisan film and kick start the career of many young directors. Admittedly, of course, all films shown had come in accordance with the censors.

Li Yang, Professor of Film Theory at Peking University - no relation to the aforementioned director - believes that these new upcoming filmmakers are taking a fresh approach to their creative limitations. ‘They neither directly criticize state ideology, nor overtly court commercial appeal,’ he states. ‘The new generation of directors is trying to strike a balance between the market, and the system, and the self.’

"The new generation of directors is trying to strike a balance between the market, and the system, and the self."

Li Yang, Professor of Film Theory at Peking University

The ever-increasing Chinese cinema market is granting upcoming independent filmmakers more opportunities to express their views on Chinese society. Only if, in the eyes of the authorities, they don’t go too far.

Featured Image Credit: IMDb / Blind Way / Authrule

Is it right for the Chinese government to take such a hardline approach in censoring cinema?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter