By Bryony Chellew, third year English

Wherever you might fall on the spectrum of the politics of war, it is difficult not to agree with Matthew Healey about the extent of its horrors. Bryony Chellew explores the Bristol-based artist's multimedia exhibition.

Matthew Healey is a Bristol-based artist, whose exhibition Broken Faces, the product of a series of sculptures, paintings and photo collages, is currently showing at the tucked-away Centrespace Gallery until the 14th November. The exhibition depicts studies of facial reconstruction surgery performed on injured survivors of the First World War, detailing the severely disfigured profiles they were subsequently left to live with.

Opening tonight: Broken Faces. Matthew Healey. November 3 -14

— Centrespace Gallery (@CentrespaceBS1) November 2, 2018

Private view: November 2, 6 - 9pmOpen Daily: 10 - 5pm. pic.twitter.com/lwZXtftAlH

In many of the paintings, potentially now superfluous/useless physical features have been left blank, or painted in a block colour. The detail and focus is undoubtedly pointed towards the facial disfigurements, whilst aspects such as the ears, neck and sometimes portions of the face are left a single colour - perhaps to symbolize the now void and irreparable nature of these features; the ears, perhaps, are blank to imply that, in an echo of their absence of detail, they hear nothing; they contain nothing.

"after the First World War soldiers with facial injuries were not invited to the Remembrance Day parades in England"

'Figure 13' depicts a man's face, where a stretch of flesh connects the right side of his nose to the place where his neck and shoulder meet; the absence of lips reveal his teeth perpetually. The inclusion of the photograph of the man on whom this work is based reveals the harrowing extent of the disfigurements he was left with, seemingly to live with on his own - as Healey points out in his exhibition notes, after the first World War soldiers with facial injuries were not invited to the Remembrance Day parades in England. Healey goes on to postulate that ‘100 years later and sadly things have not changed very much’.

Figure 13. Image credits: Epigram / Bryony Chellew.

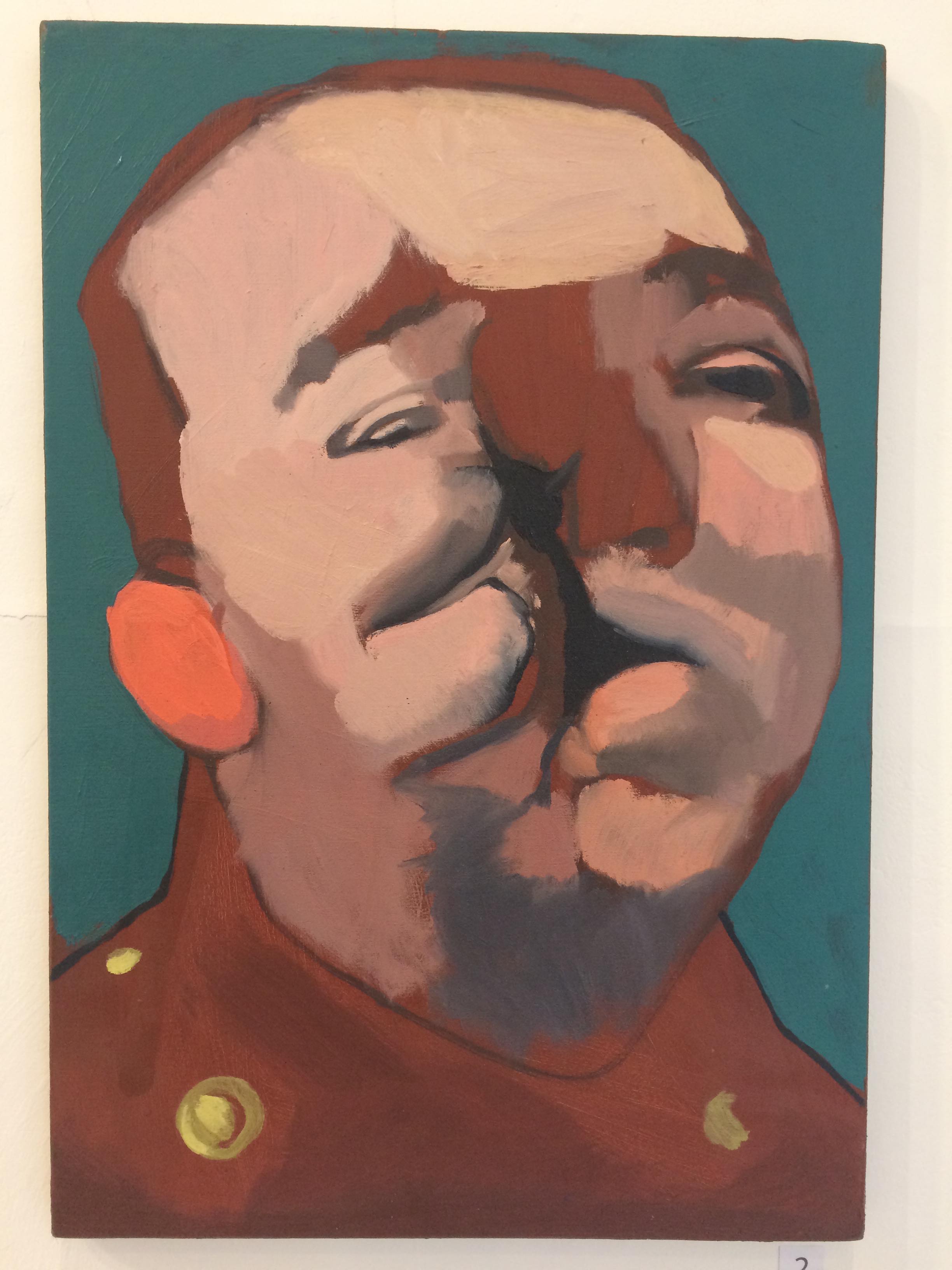

The portrait in 'Figure 8' presents a hollow where the subject’s nose should be, and their mouth is lent little to no detail; it is simply a single black line, scrawled on as if it were an afterthought. This black line is perhaps a commentary on the significance of the surgical treatments and lack of care these soldiers were provided with.

Figure 8. Image credits: Epigram / Bryony Chellew.

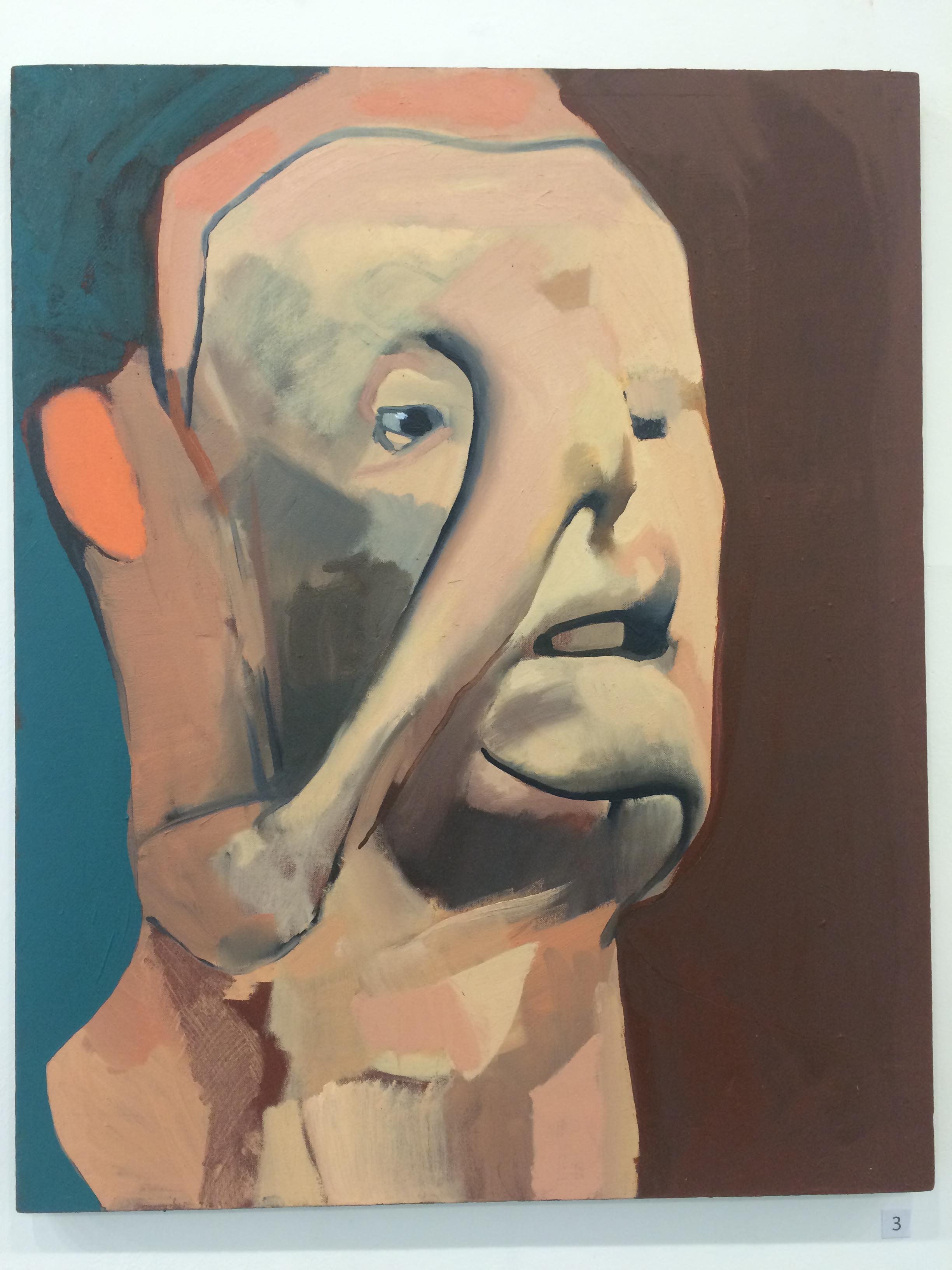

Another portrait, which is worked into a sculpture as well, shows a war victim with only a few centimetres of skin separating his right eye from caving in to join the cavernous hole where his mouth and nose evidently once were, in a horrifyingly Dalton Trumbo-esque profile. The man's tongue is still visible from the outside.

Image credits: Epigram / Bryony Chellew.

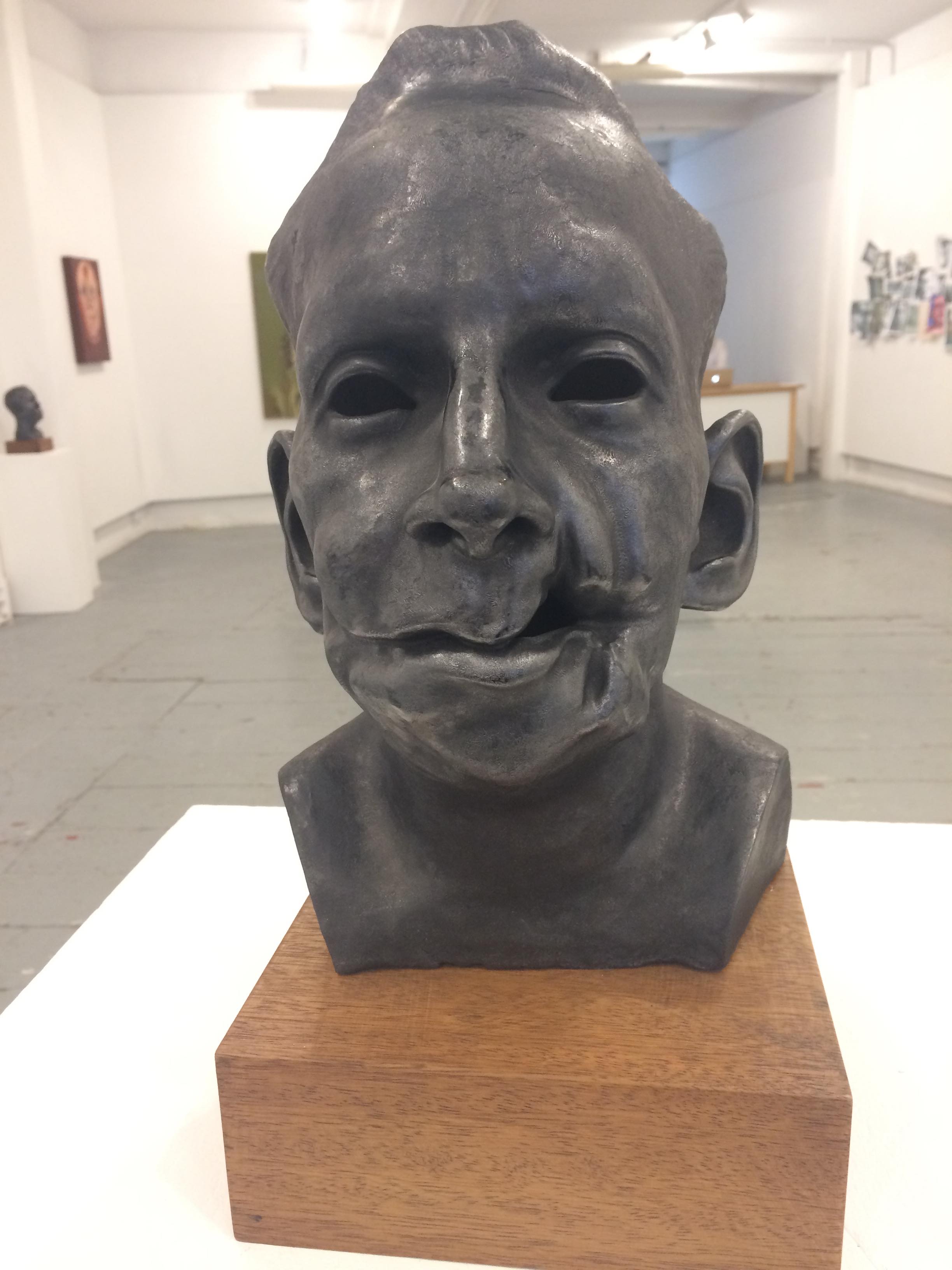

Healey’s sculptures are - perhaps deliberately - made to be ever so slightly smaller than the skull size of an average male adult, making them appear small and childlike. As well lending emphasis to the exhibition’s harrowing nature, this also serves as a grave reminder that boys as young as 14 were enlisted in the First World War, and were subjected to the horrors one finds oneself surrounded by in Healey's exhibition.

Image credits: Epigram/ Bryony Chellew.

After the exhibition, I reached out to Healey via email. He admitted that he worries ‘no one cares’, a fear which is alarmingly pertinent when considering that survivors of war are often forced to rely on charity work alone to cope with the mental and physical repercussions of their service.

Fittingly, Healey ends his exhibition with a line from Wilfred Owen as he quotes Horace:

‘The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori’

Wherever you might fall on the spectrum of the politics of war, it is difficult not to agree with Owen - and Healey - about the extent of its horrors. Leaving the exhibition, you are, quite literally, stared in the face by the horrifying realities of the First World War - a war that seems to refuse to remember those that survived it, yet carried its burden on their faces every day.

(Featured image credits: Epigram / Bryony Chellew)

What are your thoughts on 'Broken Faces'? Let us know in the comments below or on social media.