By Caitlin Danaher, Third Year, English

The metric is 34 years old and limited in what it recognises as feminist - is it still relevant today?

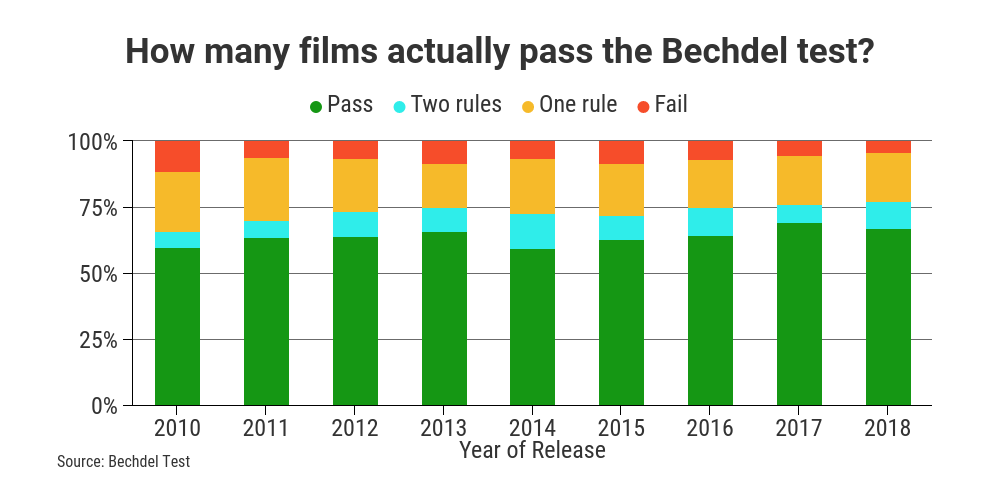

The boring paradigm of flat female characters shown in relation to complex and compelling male characters seems to have existed since the dawn of time. A 2017 survey by the ‘Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media’ found that of 120 films surveyed, only 31% of named characters were female, and only 27% had a female protagonist or co-protagonist.

Epigram / Patrick Sullivan

Alison Bechdel took this rampant gender inequality to task in her 1985 comic ‘The Rule’, in which the character stated that she would only watch a film if it satisfied three conditions: (1) the film must feature at least two named women, who (2) must have a back and forth conversation, which (3) must be about anything other than a man. The punchline being that as a result she hadn’t seen a film for six years.

To pass the Bechdel Test, the conversation could be as groundbreaking as discussing an alien invasion, or something as trivial as sandwich fillings. Indeed, Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) manages to pass the test by the skin of its teeth through two women’s conversation about the toilet. Of this year’s 'Best Picture' nominees at the Oscars, only Green Book (2018) fails the Bechdel Test. Films such as The Favourite (2018) and Black Panther (2018) pass with flying colours as we see exciting, funny and powerful leading women such as Olivia Colman, Lupita Nyong’o and Letitia Wright taking centre screen.

Yet the fact that The Favourite is still deemed ‘refreshing’ for portraying an all-female driven story is perhaps a disappointing indicator of the minimal progress that film has made towards true gender equality since Bechdel made her comic over three decades ago.

To pass the Bechdel test, two named female characters must talk to each other about something other than a man. And coined by Manohla Dargis, the DuVernay test requires “African Americans & minorities to have fully realized lives rather than serve as scenery in white stories."

— Netflix Film (@NetflixFilm) March 8, 2019

As the 2017 Oscars show, failing the Bechdel Test doesn’t necessarily identify a ‘bad film’, as both Moonlight (2016) and La La Land (2016), the two biggest winners at the awards, did not pass the test. Indeed, the test was never intended to be used as a means of evaluating a film’s quality. Many critically lauded films fail the test, including The Godfather (1972), Toy Story 1 (1995) and 2 (1999), and The Social Network (2010). Instead, the Bechdel Test illuminates the often passive and uninteresting characters written for women in film.

The test is undoubtedly limited and fails to indicate the feminist capacity of a given film. Cinderella (1950), a film in which the protagonist is saved from her miserable existence by a charming prince, manages to pass the test through a conversation involving the gendered stereotype of cleaning. Just because the women can’t talk about men doesn’t prevent writers from drawing upon other tired female clichés, such as clothes, makeup and shoes - unless of course the film is The Devil Wears Prada (2006), in which the blue sweater discussion is iconic and must never be slandered.

IMDb / Gravity / Warner Bros. Pictures

Contrastingly, Sandra Bullock’s role as a medical-engineer-cum-astronaut in Gravity (2013) fails to pass the test despite subverting a whole host of gendered stereotypes. Additionally, conversations about men aren’t necessarily ‘anti-feminist’, as evidenced through the cultural phenomenon of Sex and the City (1998-2004) which revolutionised depictions of women and their sexuality on television when it first aired in 1998.

The question arises as to how else we should judge the gender-balance of films we’re watching. Is the film presented through the female character’s perspective? Or are we unwittingly partaking in the voyeuristic objectification of women under the male gaze. Tied up in the question of gender balance are intersectional questions of race, class and sexuality. Are we seeing a wide range of female perspectives or merely those of white cis-het middle-class women? Perhaps we should focus on what’s happening behind the camera. Is the film directed or produced by a woman? What about the cinematographers, sound team or editing team?

In Regina King’s acceptance speech at the Golden Globes she called for all producers to ensure they hire ‘50% women’ for any projects they work on. Once again, the Oscars feature no women in their 'Best Director' category. In these disappointing times, King’s speech and the continuing Time’s Up movement create hope that we might see a transformed awards landscape in 2020 that adequately recognises female contributions to film.

"Everything I produce is going to be 50 percent women": Regina King voiced her support for "Time's up x2" with a hiring promise to include more women during her acceptance speech for her work in "If Beale Street Could Talk" at the #GoldenGlobe Awards https://t.co/f6sNML618e pic.twitter.com/8gkQWxfCvc

— CBS News (@CBSNews) January 7, 2019

As for the Bechdel Test, hopefully it will become increasingly irrelevant with films striving to feature named female characters who are as multifaceted, dynamic and entertaining to watch as their male equivalents.

Featured Image: IMDb / Sex and the City 2 / MMIX New Line Productions

Do you trust the Bechdel Test to rank feminism in films?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter