Annihilation is a visually unique film may have missed out on its chance to be on the big screen in the UK but got its day in the sun with Netflix instead. Its cinematography, however, seems somewhat misplaced on the small screens of streaming.

Midway through Alex Garland’s second film Annihilation comes a scene so viscerally terrifying it will haunt my memory interminably. The scene is too existentially horrifying to spoil, yet it involves a bear with a human skull for a head, the disembodied, blood curdling screams of a departed companion and a pervasive quality of powerless dread that recalls both Hitchcock and Francis Bacon. It will surely be remembered as one of the finest cinematic scenes this year. It is also one that residents of the UK will probably never get to see in a cinema.

Annihilation is the sort of film cinemas need to survive in the Netflix age; a film layered with a sense of spectacle that simply cannot be replicated on a laptop screen that simultaneously tackles far weightier themes than most blockbusters would even attempt. Whilst it often falters in examining those themes with the philosophical rigour they deserve, it’s still a genuinely ambitious, often ecstatically realised work of science fiction. Yet in a cruelly ironic twist, the film has been dumped straight to Netflix by a studio that deemed it ‘too intellectual’ to make money in cinemas.

Regardless of whether or not the studio was right, the fact that selling off a film to streaming services without a chance for people to see it in cinemas is now even an option sets a dangerous precedent for the future of the multiplex. It’s especially damaging in cases such as Annihilation, a film whose dizzying visual ambition is muted when viewed on a computer screen (or god forbid, a smartphone).

Following a team of five female scientists as they enter a mysterious anomalous zone known as ‘The Shimmer’, one might be confused during the film’s first hour as to why the studio balked at Annihilation.

Indeed, the film’s opening half deals almost exclusively in stock characters and B-movie cliches. Despite featuring some of Hollywood’s most talented female leads, actors such as Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez and Tessa Thompson are attributed with thin characters whose motives, while interesting on paper, are explained within the film through rote exposition.

Yet in a cruelly ironic twist, the film has been dumped straight to Netflix by a studio that deemed it ‘too intellectual’ to make money in cinemas.

Likewise, the various action and horror set-pieces in the first hour fail to inspire, whilst there are some truly bizarre compositional techniques employed throughout the film; the relentless centre-framing of characters with ugly dead space behind them is perplexing.

Yet as the film goes on, it settles into an eerily existential groove as it delves into its funhouse-mirror depiction of a world where biology has gone awry. As the minds and bodies of the characters start to collapse and even intermingle, the film creates images that are both memorably haunting and genuinely gorgeous, finding a perverse and horrific beauty in decay.

The film’s stunning production design - which creates an expressionistic world built from the fractured psyches of its characters - manages to elevate the film beyond its often two-dimensional dialogue scenes and flat, washed out cinematography.

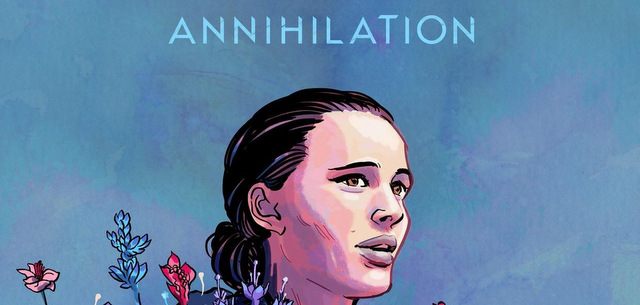

The studio’s rejection of Annihilation becomes clearer when one reaches its sumptuously radical finale. Doubling down on the film’s elegiac examination of humanity’s capacity for self-destruction, the film’s climactic pas-de-deux between Natalie Portman’s Lena and an uncanny stalker is a giddily hypnotic piece of genuine avant-garde cinema.

The film’s thin characters and relentlessly simplistic overuse of cancerous imagery prevent Annihilation from attaining the cerebral complexity it yearns for, yet its finale is executed with such genuine visual awe so as to affect the viewer on a more visceral level.

Comparisons have been drawn between Annihilation and the ponderous portent of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, as well as the visual experimentation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. To be sure, Annihilation never reaches the psychological profundity of either of those reference points. Yet there are few big-budget sci-fi films today that would even attempt to, and when Annihilation lets its mesmerizingly melancholic imagery speak for itself it transcends whatever issues its screenplay might possess.

Photo by Flickr / junaidrao

It’s especially cruel that this flawed film’s finest qualities - its magnificent horror scenes and spellbinding spectacle - are the ones that have been hurt the most by the decision to forgo a cinema release.

In an age of safe bets and bean counters, it’s increasingly likely that studios will continue to view challenging, risky, big-budget sci-fi as not worth the expenditure. When (and if) films like Annihilation are released, they may well suffer the same fate of being dumped on the internet by executives that assume there isn’t an audience for progressive and adventurous blockbuster cinema. Prove them wrong.

Photo credit: Youtube / Paramount Pictures