By Amelia Jacob, Film & TV Digital Editor

Perhaps the video you saw on TikTok was an elegantly positioned novel on a floral bedspread, or a cosplay of the characters from a fantasy series. Maybe it was a pile of aesthetically pleasing art books bathed in sunlight, as a trending audio played over and over in the background. Possibly, it was a dramatic reading of a poem by Richard Siken, or a zoomed-in video of a young woman crying over the last page of a romance novel. If any of these videos sound familiar to you, you may have stumbled across BookTok, a relatively recent sub-category of TikTok that has gained immense traction since the term was coined in 2020.

On BookTok, reading became cool again. According to The Financial Times, BookTok videos have earned almost 56 billion views over the past four years. The creators of these videos are referred to as BookTokers, and they often reach hundreds of thousands of followers online, regularly posting content that includes well-paid endorsements for publishers and distributors alike. These videos frequently take the form of recommendations or lists and include key words or phrases such as: “enemies to lovers” or “dark academia”, both tropes in novels that frequently go viral within the community.

The work of influencers such as Jack Ben Edwards and Dakota Warren is a good example of the content BookTok produces, and the influencers’ book recommendations are eagerly received by their followers. They have tailored their content to aesthetically align with the literature they post about, with high-performing results.

A video of Warren drinking wine, for example, complete with velvet bows in her hair, or a video of her covered in fake blood with a suitably hedonistic novel like The Secret History lying next to her, will often generate over 200 thousand views. Both Warren and Edwards make reading aspirational, aestheticising the accumulation of books and knowledge.

For publishers too, such recommendations are gold-dust, often igniting an intense period of sales that pushes authors straight into The New York Times bestseller list. For a while it seemed as if the publishing industry was struggling to align itself with influencer culture. However, the fluid video format of TikTok’s platform facilitated an online community that seems passionate about reading in a way Twitter and Instagram users couldn’t quite pull off.

There are several positives to this book boom. What objection could anyone make to a trend encouraging people to ditch their phones for a brief period and lose themselves in a story? Reading exercises the brain, a discipline sorely needed after life moved almost solely online during national lockdowns. It is also widely proven to improve sleep, concentration, and general well-being in young people.

Crucially, it promotes an accessibility to reading that removes class barriers, creating a strange space in which Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life can go viral at the same time as Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo. I have read and enjoyed both novels, yet the former is a tragedy Aristotle would be proud of, an epic that spans the lives of four young men in New York with graphic depictions of violence and assault. The latter is a frothy and emotional novel about a 1950s film star and the ups and downs of her career. The distinction in quality, length and content between these novels is clear, yet both are highly regarded by the BookTok community.

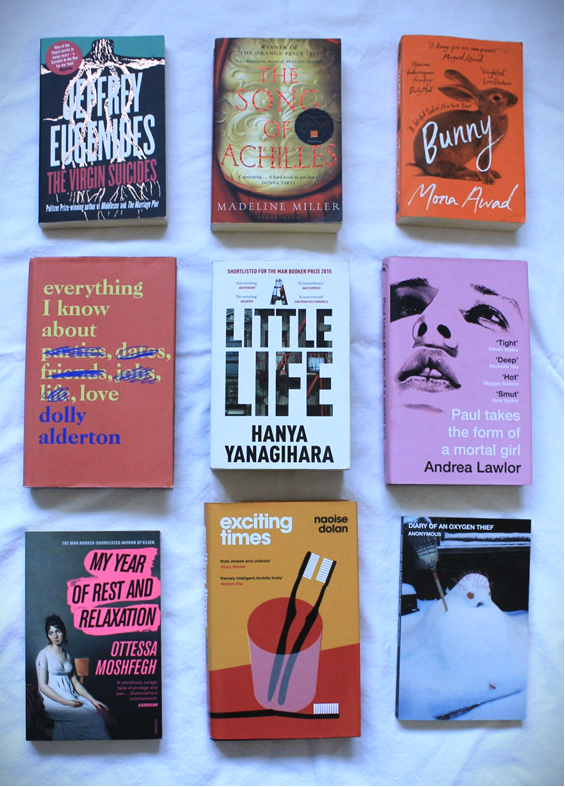

Yet whilst it is an overwhelmingly positive space online, sometimes BookTok is somewhat hindered by its audience, who are often in agreement that romance and/or young adult fiction is best, and often tailor the community to these genres alone. It is necessary to separate the wheat from the chaff to find a recommendation that suits older readers. Novels like Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides or Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, for example, are just as accessible as their YA equals, yet they are far more complex in plot and characterisation, and therefore more rewarding for older readers.

It can be slightly frustrating when terrible novels gain traction on BookTok. Does Colleen Hoover deserve to share the same stage as Hanya Yanagihara? I would argue not. But BookTok is larger than my personal opinions. By giving readers what they want — the space to be enthusiastic about any books they enjoy — there is room for everyone to co-exist. What could be better than that?

The Best of BookTok:

- Paul takes the form of a mortal girl - Andrea Lawlor

- Everything I know About Love - Dolly Alderton

- Bunny - Mona Awad

- A Little Life - Hanya Yanagihara

The Worst of BookTok:

- Exciting Times - Naoise Dolan

- Diary of an Oxygen Thief - Anonymous

- It Ends with Us - Colleen Hoover

- A Court of Thorns and Roses - Sarah J. Maas

Featured Image: Courtesy of Amelia Jacob

What has been your favourite 'BookTok' read?