By Euan Merilees, Third Year, Philosophy

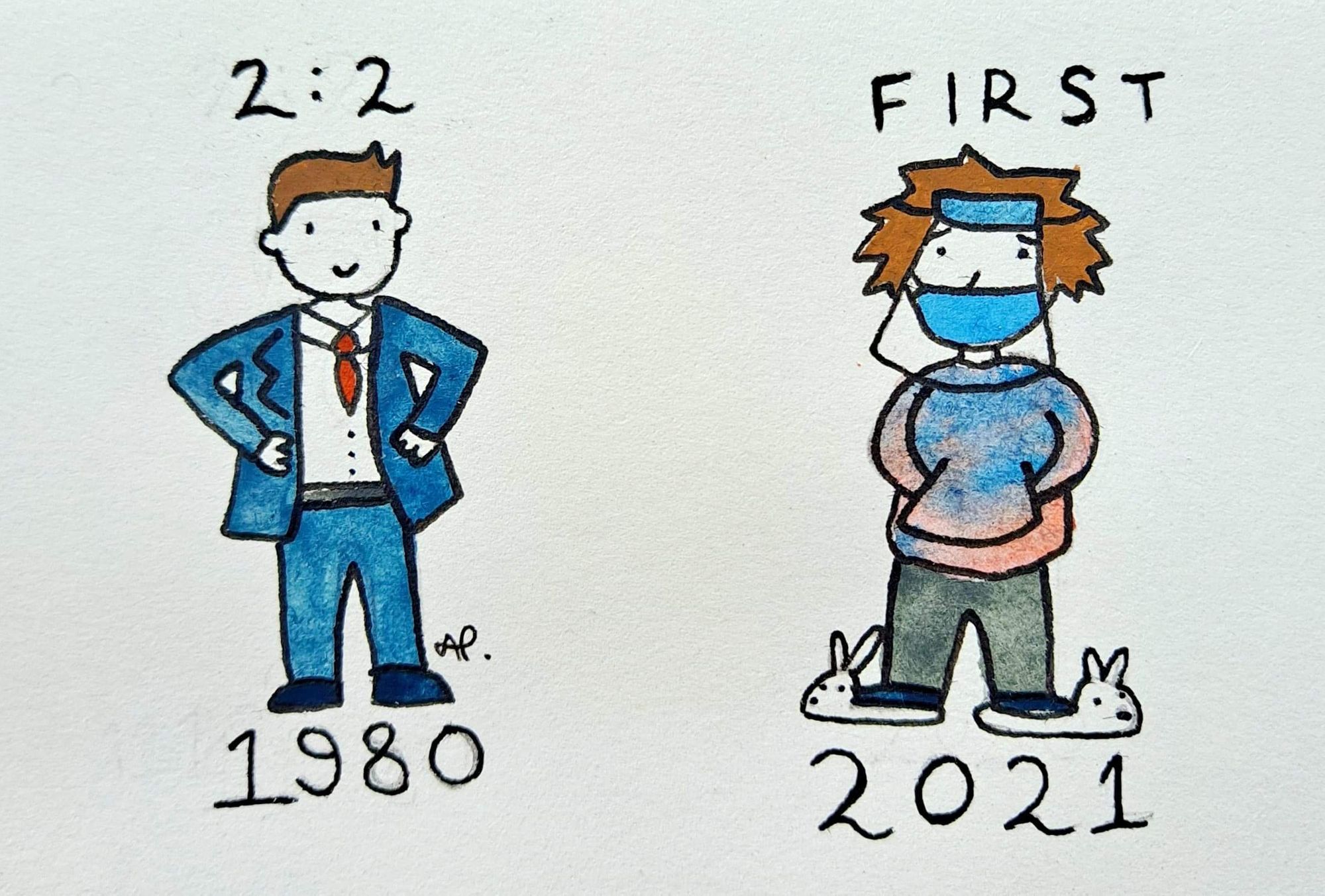

It is a general rule of thumb that as the quantity of an item increases, the value of the individual item decreases. This applies to grades as well. As more students achieve “good grades”, the value of achieving that grade diminishes. This is pretty disheartening, and it is made worse if the inflation occurs not because people of getting smarter, but because of random external factors like a global pandemic.

The “no detriment” approach to results during the Covid pandemic caused the proportion of students attaining first-class degrees to increase. Additionally, the reduced examination and assessment workload means our fees of £9,250 a year pay for a less rigorous, challenging, and rewarding degree than the ones our predecessors completed.

This means that not only has our educational experience suffered because of the pandemic, but the grade we achieve is worth less than it would have been in a normal year. Personally, I feel as if the world has kicked us in the teeth.

While pandemic related grade inflation seems depressing, I believe that the problem it poses is less severe than we realise. Additionally, grade inflation because of Covid could be considered a good thing for the current cohort of students graduating this year. The reason for this is to do with the wider issues that have been plaguing the university experience over the last thirty years.

Grade inflation is not a new phenomenon. Over the last 25 years, the number of students getting first and upper seconds has leapt from 47 percent to 79 percent. This isn’t because people are getting smarter. A 2009 study done by King’s College compared the results of 3,000 students sitting a mathematics paper from 1976 and found that the class of 2009 did about as well as the class of 1976, even though the class of 2009 attained considerably higher grades in their 2009 exams.

So why has this natural rate of grade inflation occurred? Many reasons have been offered; however, the most cynical critics say that it is the result of the great university scam where the high proportion of good grades create a “world-class” reputation for British universities, attracting high-paying international students to UK universities.

Our grades are increasing, but our employment prospects are decreasing

Whatever the reasons may be, the fact of the matter is that grade inflation is a longstanding existing phenomenon. A 2:1 in 2020 may not be worth as much as a 2:1 in 2019, but the difference in value between a 2019 2:1, and a 1989 2:1, is far greater than the previous difference.

Considering the existing problem, what does it matter if the cohort of 2020-2021 achieves slightly higher grades than previous years? Especially considering the stress, hardship, and horror we’ve all endured while staying sane and completing our degrees.

The Office for National Statistics shows that 63% of students have reduced mental health since the start of the 2020 term. Additionally, graduating students face a more competitive and overcrowded job market than ever, with one in eight graduates hit with unemployment. This is not grade inflation, this is grade stagflation. Our grades are increasing, but our employment prospects are decreasing.

Opinion | Grade inflation does not matter

The struggles of LGBTQ+ students in lockdown

The underlying question is how can we treat students fairly during such exceptional and unique circumstances? Policies like “no detriment” are supposed to recognise that the exceptional struggle we had to endure must have negatively affected our studies.

Grade deflation, where students received lower grades because of the pandemic, would damage the prospects of most students far worse than grade inflation. Furthermore, a one-time jump in grade rewards students for going through the great achievement of completing a degree during a pandemic, something worth celebrating.

All in all, grade inflation resultant from the pandemic should be thought of as “grade quantitative easing”, as the increase would benefit students more than pretending the pandemic never happened.

Featured Image: Unsplash / Green Chameleon

Do you feel your grades have been affected by Covid-19? Let us know!