By Alexander Sana Sampson, First Year English Literature

The recent outrage over the abduction and murder of Sarah Everard has sparked a national debate surrounding women’s safety in public. Women have expressed emotions from anger to despair, fear and a passion to evoke change, and some men have followed in asking what they can do to help women be and feel safer on the streets.

However, there remains a fundamental issue: the men who most need to engage in this debate are the ones who probably aren’t paying attention. Men whose culture is to catcall and wolf-whistle, sliding up a scale to those who view a woman alone at night as an opportunity – these men are unlikely to change their behaviour through a spate of social media posts or renewed calls from feminist activist groups.

Bristol Women's Commission's #ZeroTolerance initiative saw more than 70 organisations sign up to the pledge to help eliminate gender-based violence in the city.

— Bristol Women’s Commission (@BWCommission) March 26, 2021

There is a clear commitment to tackling this in #Bristol - to make it a safer place for all women and girls. pic.twitter.com/oOWRVsAM3Y

Bristol is one of the the worst cities in the UK for gender-based street harassment. This statement stands as a result of many complex, intersecting issues highlighted by a report commissioned by the Avon and Somerset Council in 2018.

Amongst other factors, the report notes that Bristol holds higher rates of mental health related issues, ethnic minorities, opiate and cocaine usage, alcohol related hospital admissions, and unemployment compared to the national average.

These elements hold a correlative relationship with issues within the general state of ‘toxic masculinity’ today: notably, the need for power and control in a relationship; the ideal of a submissive woman as seen online; an inability to express emotion healthily; the idea that violence gets (immediate) results; unresolved intergenerational issues... the list goes on.

In the public sphere, actions from chauvinism to rape speak of a need for attention and/or desire for power over someone; this ultimately suggests an individual yearning for control due to a sense of entitlement ingrained in masculine culture.

Bristol University and the Bristol Students' Union have called for "culture change" in a new joint statement following the murder of Sarah Everard. https://t.co/kHoPwAk9AA

— Epigram (@EpigramPaper) March 23, 2021

Many charities in Bristol work to deal with the issue of street harassment. Amongst others, Bristol Zero Tolerance, an action group attached to Bristol Women’s Voice, is using their Bristol Street Harassment Project to highlight the impact of public harassment.

However, despite the many organisations doing fantastic work helping women recover from harassment and men in preventing re-offence, the vast majority of charities working in this area fall into the bracket of reactive philanthropy.

Their work “picks up the pieces” and is thus very important but offers only a reactive, short-term response to an issue endemic throughout society.

In looking for a long-term solution, there are no easy answers. Different key voices, both male and female, call for a mix of approaches including education on respect and equality from a formative age, creating environments where boys and men can express their emotions and be vulnerable, and increasing the legislative consequences for men who harass.

Notably, according to masculinity activist and author Chris Hemmings, who gave a virtual talk at the Univeristy of Bristol only last term through TED Ideas society, a potential roadmap for tackling this problem at its roots begins by shifting the emphasis of the debate on street harassment from female safety to male violence.

His logic follows that in focusing on this as a male problem, all men will have to take responsibility for this crisis. Ippo Panteloudakis, Head of Services at Respect Phoneline, a charity working to help those who are perpetrators of domestic abuse, agrees:

‘Those [men] that are termed “unreachable” - they’re not interested in getting help and there’s nothing you can do. But what you can do is [get] everyone else around them to send the right messages... If they feel isolated and no one puts up with those [harassing] behaviours - that’s when the problem will stop.’

‘Social settings where casual misogyny, cat-calling and other more serious harassing behaviours are called out would hopefully create an environment where these behaviours become socially unacceptable.’

Panteloudakis notes that for men who eventually reach out for help, after recognising their abusive behaviour in some form, there is a common denominator:

‘The reason they get in touch can be summarised in one word: loss. They lose their freedom if they’ve been in prison, or their partner might have left them, or they’ve been given an ultimatum. Or it might be the loss of respect. If you lose everyone else’s respect then you’ll stop doing it. That’s for sure.’

Consequences in social settings, where casual misogyny, cat-calling and other more serious harassing behaviours are called out, would hopefully create an environment where these behaviours become socially unacceptable.

Candlelit vigil held on College Green in memory of Sarah Everard

What you need to know about the university’s policies on sexual harassment and sexual violence

Significantly, the reality for this issue is that it is complex and raises more questions than can be answered here. For example, at the heart of this entire problem lies a power imbalance. How do we address this? In what way do we educate boys and men to uphold respect and equality? How can we teach men empathy and help them feel safe enough to express their emotions? How can we improve the current criminal justice system so that women have confidence in reporting harassment?

However, in opening up questions and in sustaining conversation on this matter, it remains relevant in the public consciousness as the crisis it is.

If you are looking to educate yourself or those around you further please look into the follow literature and resources as a starting point:

‘The Descent of Man’ – Grayson Perry

‘Be A Man’ – Chris Hemmings

‘Men and Violence’ – BBC Women’s Hour, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000t6kt

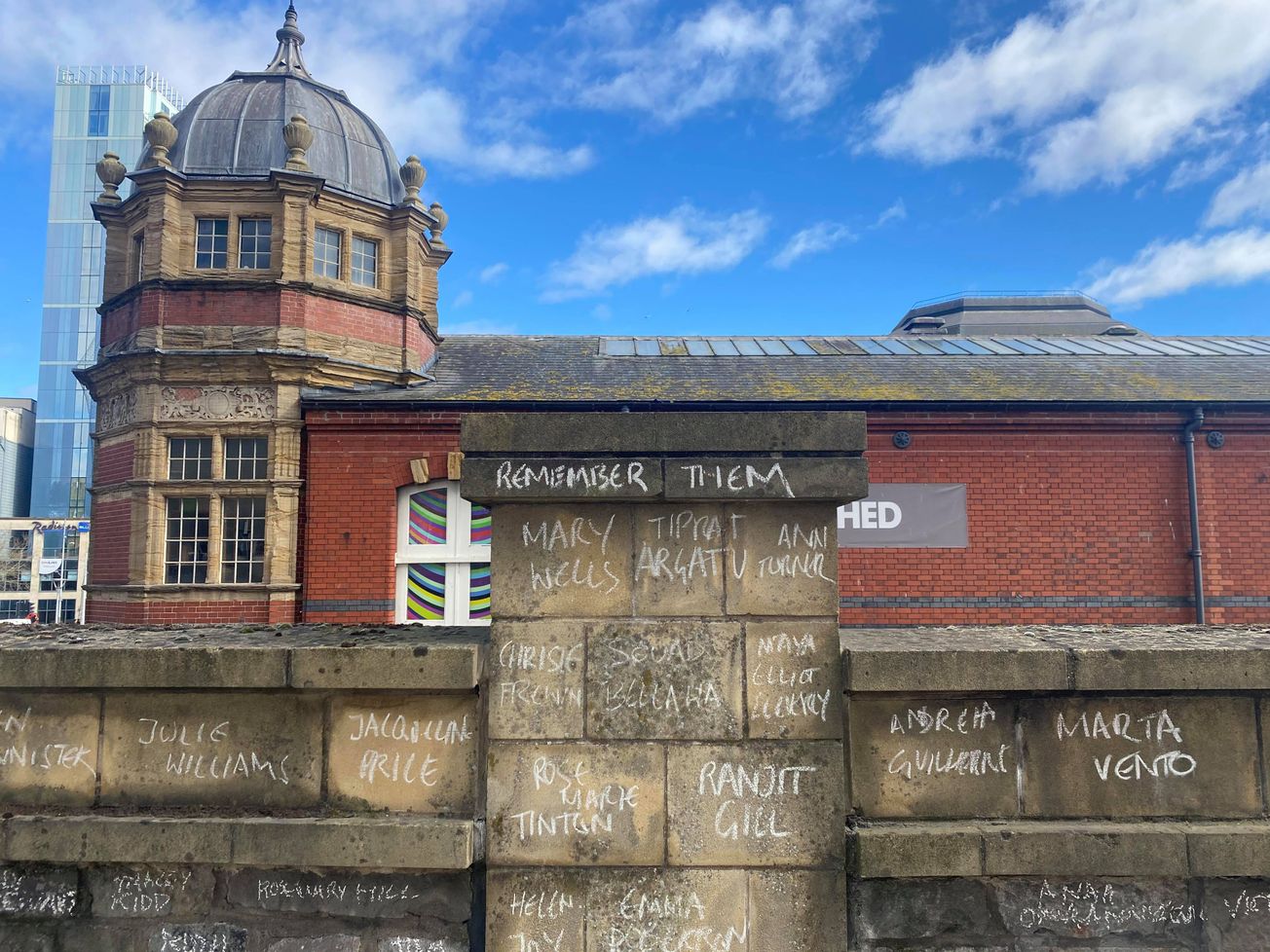

Featured Image: Epigram / Alexander Sampson